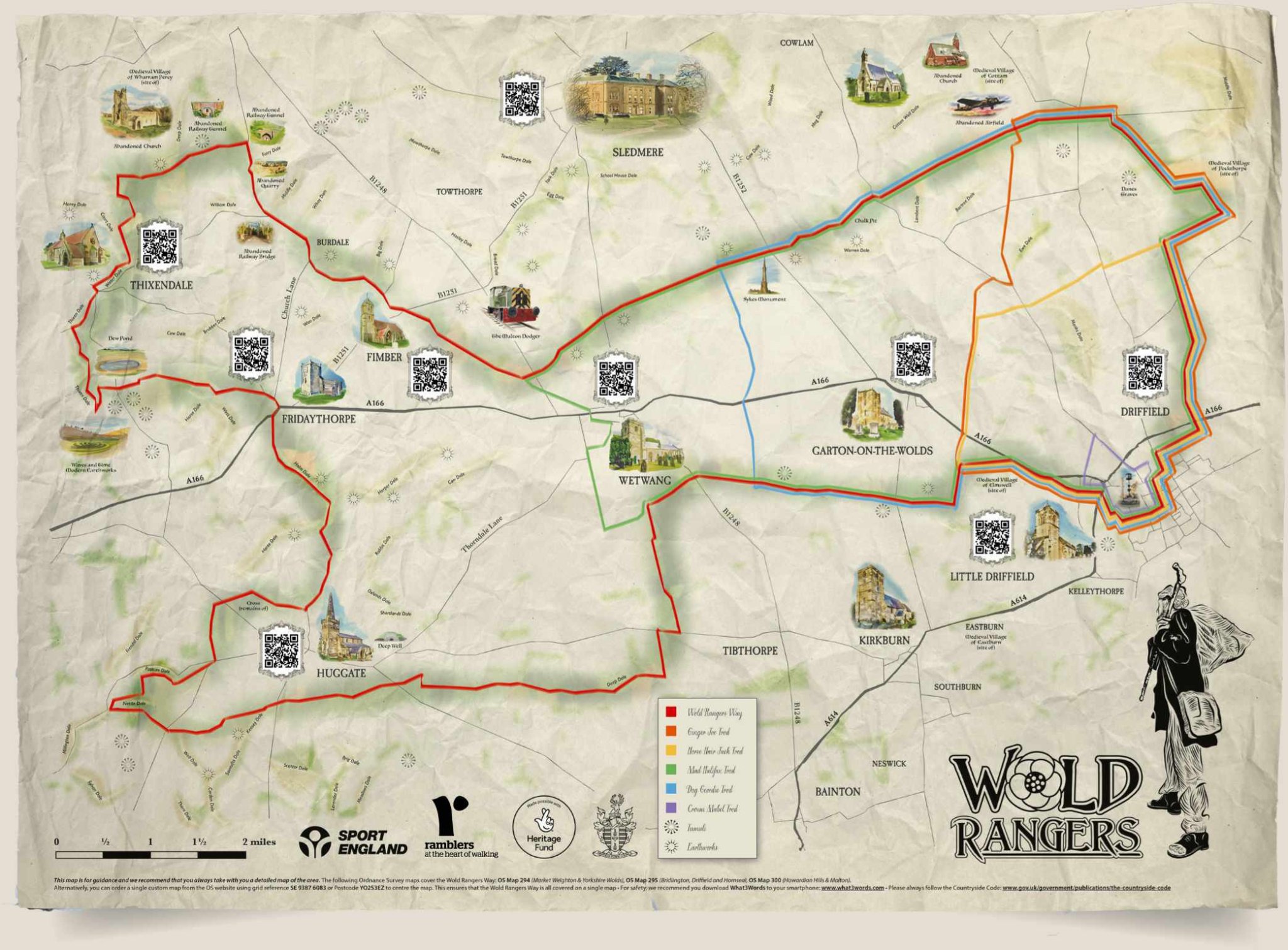

In the low hills of Yorkshire’s East Riding, new walking routes celebrate the Wold Rangers, a nomadic people who once wandered the Wolds’ green lanes and bridleways. Paul Kirkwood follows in their footsteps

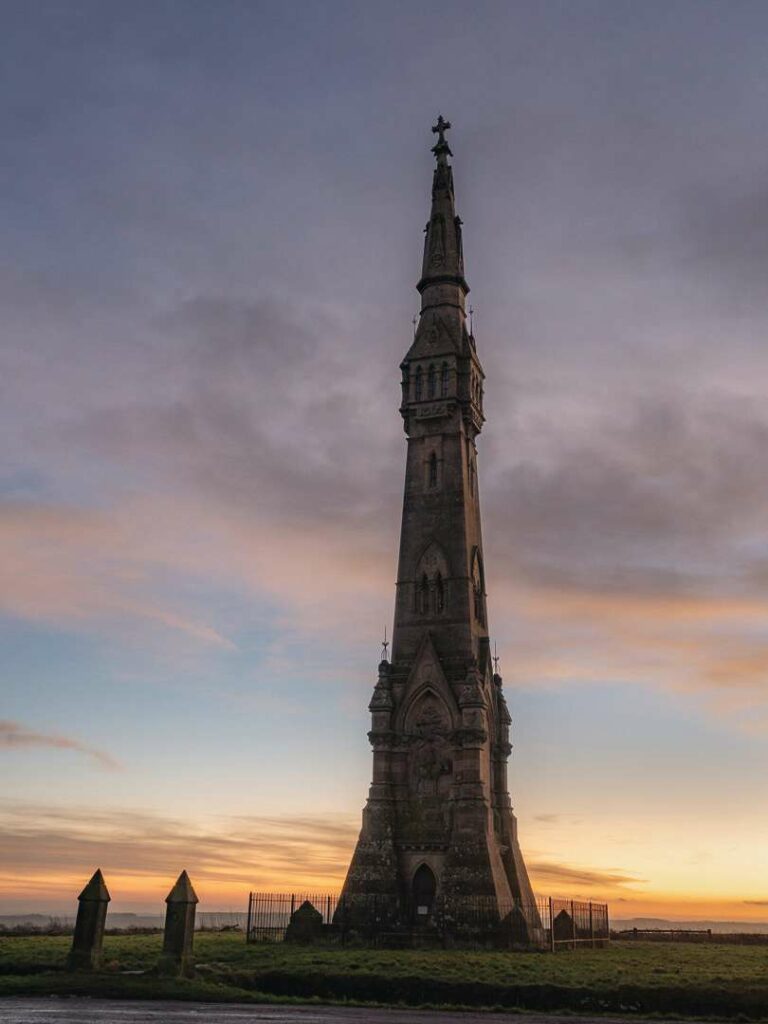

The Sir Tatton Sykes memorial pierces the sky like the slenderest minaret. From its base, views extend as far as the eye can see. On this bracing midwinter’s day, winds rush across the prairie landscape.

Minutes later, I’m in the Triton Inn in the estate village of Sledmere, beside an inglenook fire with a pint of Wold Top in front of me.

I’m on the trail of the Wold Rangers. They were a group of only around 50 people at any one time, mainly men, who roamed the Wolds in the 19th and 20th centuries, typically moving from farm to farm in search of casual work. They were vagrants, but local people also remember them fondly as lovable rogues and consider them a unique aspect of the culture and heritage of the Wolds.

The memorial was built in 1865 in honour of Sykes, one of many supportive landowners, and would have been a familiar landmark to Rangers who kipped in thickets such as the adjacent Black Wood, drank at the Triton in Sykes’ estate village and gathered around its forge when the temperature dipped.

Nearly entirely dedicated to agriculture – arable in particular, which suits the thin and chalky soil – the Wolds covers an area of about 400 square miles within a triangle cornered by York, Filey and Hull. A wold is an area of unforested, high open land and, while wolds are found across England, the Yorkshire Wolds present a singular vista. The valleys have uniform depth and gradient, yet none have rivers, due to porous underlying chalk. Erosion along geological faults shattered and hardened the chalk, leaving dry V-shaped valleys that were probably eroded by run-off from ice sheets and infilled by subsequent deposits, resulting in flat floors.

THE EMPTY WOLDS

Yorkshire is blessed with national parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Tourists flock to the Dales, North York Moors, South and North Pennines and coast – but few venture to East Riding, home of the Yorkshire Wolds. Even on a fine summer’s day, you are likely to have the Wolds largely to yourself, and in winter that is pretty much guaranteed. I often favour the Wolds for a walk in December or January, as they are drier and better drained than western, hillier regions. The scarcity of trees – cleared long ago for agriculture – means the Wolds’ stark appeal and big skies are seldom obscured and you never have to venture far before coming across a village pub to get warm and fed.

Villages are evenly scattered over the region but the Wolds have only three towns: Pocklington, Market Weighton and Driffield. The capital, with a population of 13,000, Driffield is often overlooked by holidaymakers on the town’s bypass heading for the coast. As a centre for trade and farming, it was a key location for the Wold Rangers.

RANGING ACROSS THE LAND

Drawn by the Wolds’ long-held tradition of East Yorkshire hospitality, the Wold Rangers walked the ancient green lanes between farms, seeking shelter, food and work, such as sheepshearing, potato-picking, cesspit cleaning and harvesting. Tatton Sykes, for example, hung a bell over the back door of his Sledmere House and said that anyone who rang it would be given a meat sandwich and mug of tea. In return for their labour, Rangers were sometimes invited to eat lunch with the farmer’s family.

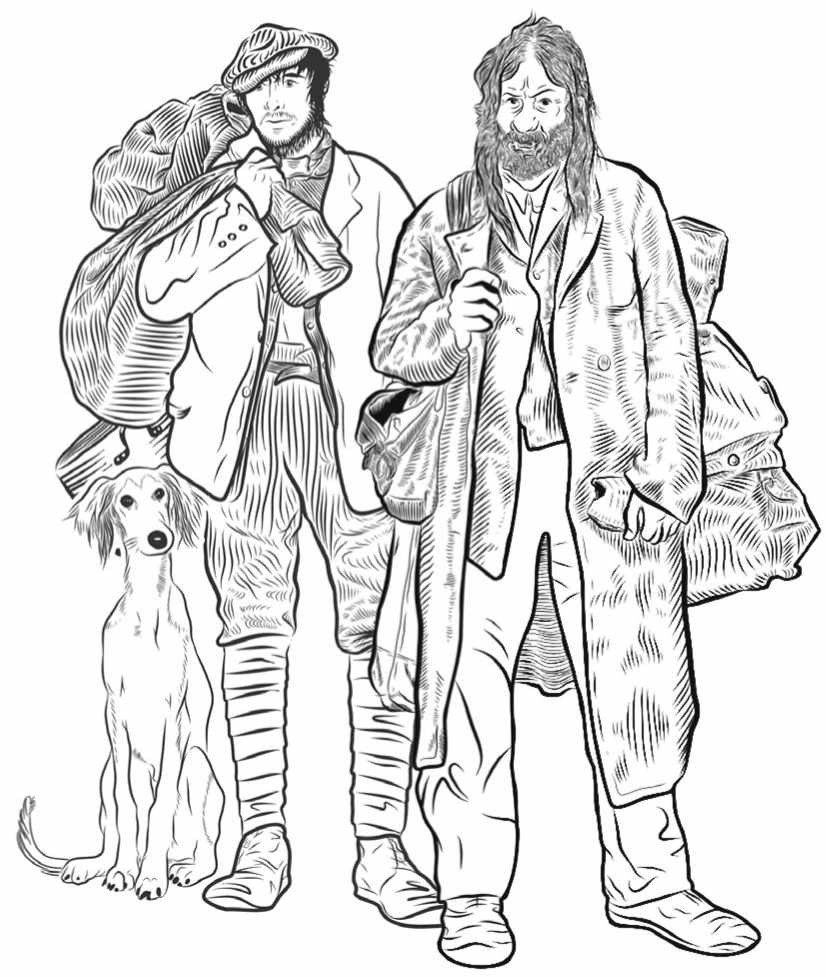

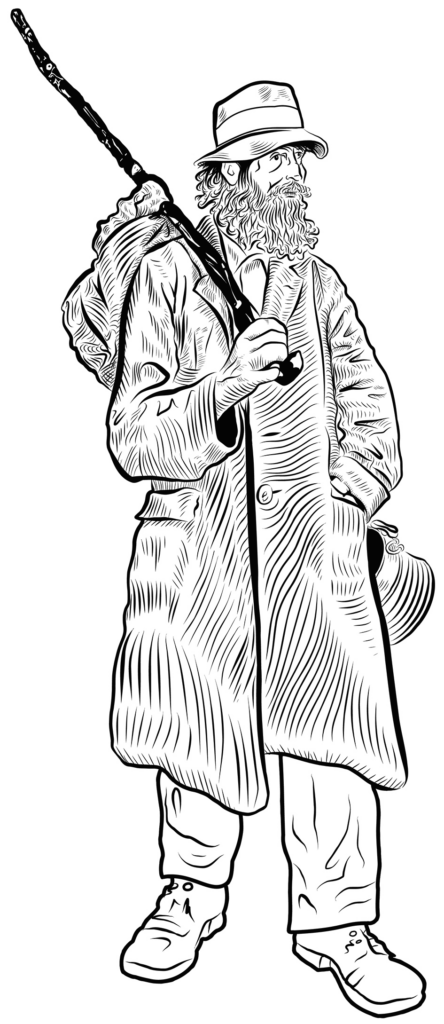

They carried their few possessions with them and slept where they could – in woods, chalkpits (Burdale Quarry north of Fridaythorpe is a prime example) and barns, sometimes with permission, often not. Colourful and often slightly intimidating characters, some Rangers were known by their nicknames, including Mad Halifax (likened to a demented scarecrow), Dog Geordie (never without his faithful lurcher) and Horse Hair Jack (who used to pilfer horsehair collected by plough boys for sale to upholsterers). Many were shady figures drifting into and out of sight across the fields.

Although the origins of most Rangers are unclear, there are several possible reasons for their existence, adding to their ranks as generations went by. The Industrial Revolution removed traditional rural crafts to towns; the 19th-century agricultural slump reduced employment on the land; and the dramatic upheaval of the Enclosures Acts of the 18th and 19th centuries deprived ‘squatters’ of common land. Some Rangers were soldiers returning from the Crimean, South African and First World Wars, who may have been traumatised by their experiences and didn’t wish to re-enter society.

PORTRAIT OF A WOLD RANGER

Ginger Joe was perhaps the best-known Ranger. Named after his beard, he was erudite and had the air of a gentleman. In 1925, when King George V and Queen Mary visited Sir Mark Sykes, son of Tatton, they inspected the new Waggoners war memorial. There they found Joe, settled in his favourite spot on the lower step, refusing to budge or even doff his hat, despite efforts by the local constabulary. He lived out his days in a box on Sledmere House Farm accompanied by his beloved dog and his hen, tethered with a string on her leg, who laid him his daily egg.

DOWN TO EARTH

“Hardy, unpretentious and very friendly,” is how Claire Binnington of Driffield Town Council sums up the personality of local people, a description that would apply to the Rangers, too. She helped devise the Wold Rangers walking routes with council colleague Mark Blakeston in 2021. The Rangers had previously been commemorated in a book by Angela Sykes (granddaughter of Sir Tatton), which provided much of the historical information for the walk routes, and in a song called ‘The Last of the Wold Rangers’ by folk group Beggar’s Bridge.

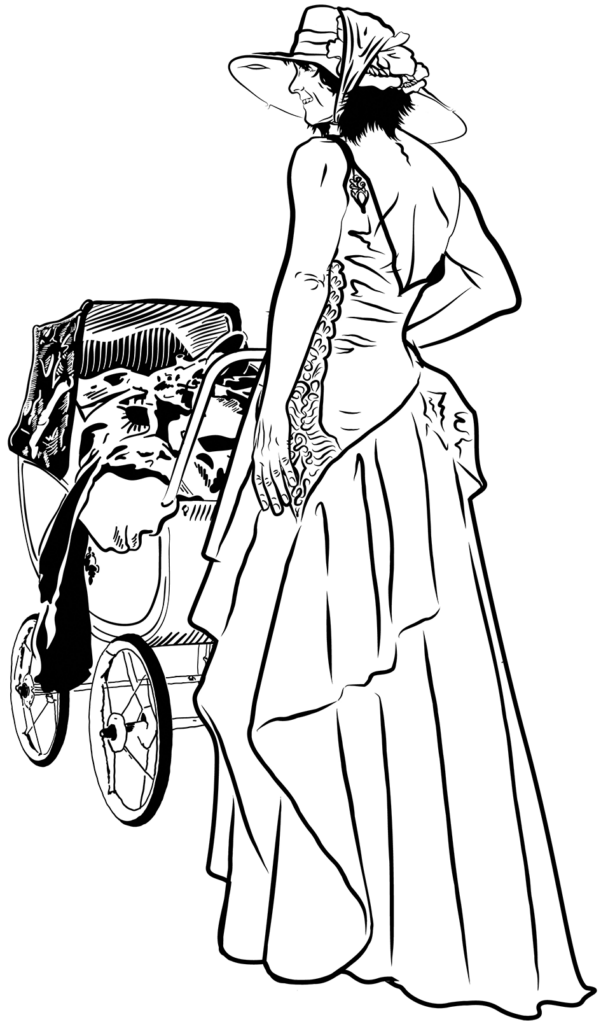

Five walking trails relate to ‘trods’ (footpaths) followed by Rangers. One is named after the very last Wold Ranger, Croom Mabel (1900–1990). It follows a route she would have taken from her home in Little Driffield, pushing a pram containing clothes she had collected from farmers’ wives to sell as rags in Driffield.

Mark said: “We were careful not to romanticise the Rangers in designs for our trail publicity. We depicted Mabel (left) as something between an elderly tramp and a strong, pretty woman in her prime.”

HARSH EXISTENCE

Life on the road was tough, particularly in winter, when some Rangers – described by Claire as “ragtag and bobtail” – committed minor crimes, anticipating being sent to police cells or workhouses where they could get out of the cold. Challenges faced by Rangers – such as mental health issues, displacement and dispossession – chime with modern times, while their connection with the local environment is something that many people experienced during the pandemic.

Mark explains that the Wold Rangers Way has been set up as a charity, partly to protect it in future and also with the intention of promoting the mental health benefits of getting outside and walking. He leads guided walks around the trods and, every Monday, a fellow Driffield volunteer takes walkers around the Croom Mabel trod, sometimes attracting up to 20 people, many of them women.

The full 43-mile Rangers circular walk formed the basis of an ultramarathon last spring, while a sponsored walk around it has raised money for Brain Tumour Research. Last summer saw the launch of a six-mile, fully wheelchair-accessible Beating the Bounds route around the Driffield parish boundary and the town’s first annual walking festival, complete with a ‘drumming up’. This was the name Rangers gave to overnight campfire get-togethers with game stews and beer. Other plans include a steel sculpture depicting Rangers and a ‘geo-walk’ tracing geological and archaeological features near Thixendale.

I end my day there. It’s my favourite Wolds village, so deeply secreted in a valley that it was reputedly the last place in the UK to receive a regular TV signal in the mid-1990s. As the sun sets and smoke rises vertically from chimneys, I walk past a chalkpit, wondering if Rangers once slept in it; and then down to a restored dewpond like an infinity pool. Storing rainwater rather than dew, the ponds used to sustain livestock – and Rangers, I suspect.

At the bottom of the valley and now completely in shadow, I come across Waves and Time, a landform artwork by Chris Drury, which mimics the surrounding landscape, the miniature valleys just thigh-high.

I don’t see a soul in the chill stillness. A murder of crows flies past. The only sounds are geese, the chink-chinking of blackbirds heralding the end of the day, hooves of a mud-coated horse as it gallops up and away from another dewpond, and cackles of pheasants echoing around the head of the valley. For a moment, I’m at one with nature – just like the Wold Rangers in this overlooked northern nomadland.

THE WOLD RANGERS WAY

The full Wold Rangers Way is 43 miles and best tackled over a long weekend. There are five other trods (as in trodden ways or footpaths), from three to 17 miles. The most popular is Horse Hair Jack trod (nine miles) while Mark Blakeston rates the section on the full route between Huggate and Hawold as his favourite – “absolutely stunning”. The author’s stroll from Thixendale described below is 3½ miles. See bit.ly/Thixendale.

Driffield is the obvious base for the routes as they all start from its marketplace. Look out for other accommodation in village pubs and B&Bs. All colour coded and waymarked, Wold Ranger routes are generally flat and well suited to all walkers. See woldrangersway.org

Paul Kirkwood has been exploring, writing about and photographing every corner of Yorkshire since moving there in 1994. A wild swimmer and camper, he has a keen interest in quirky local history.