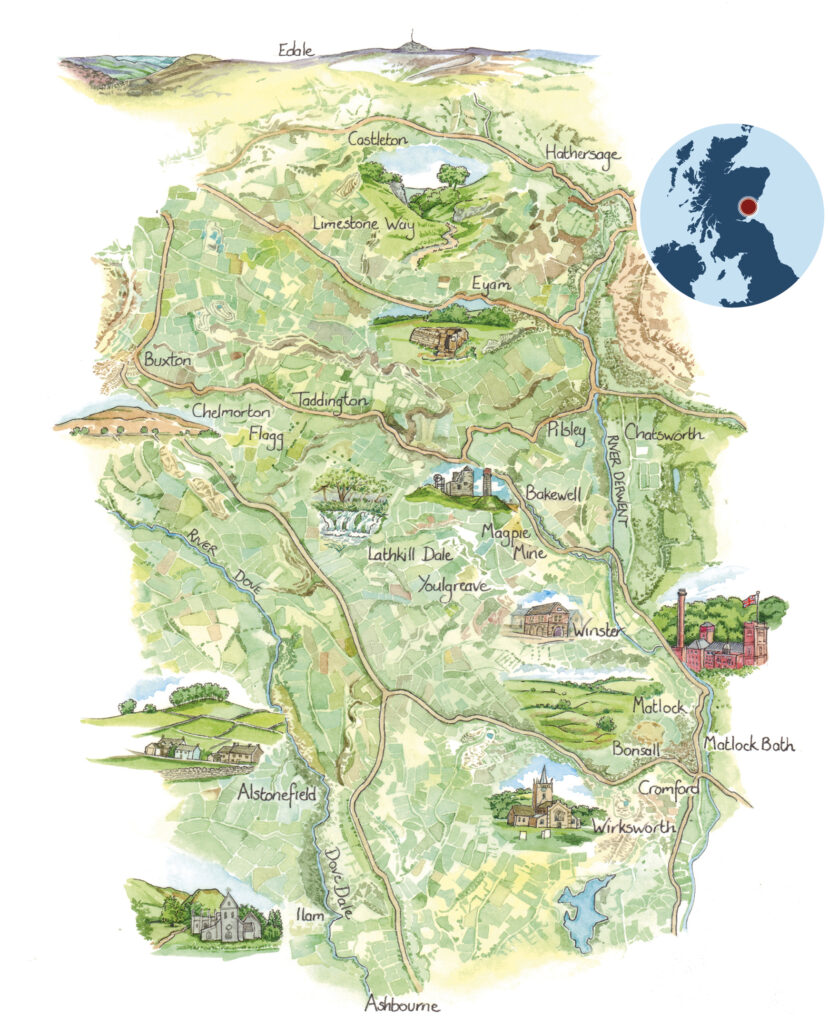

The Reclaimed Peak

Explore the beautiful Peak District in winter, where strange and thrillingly atmospheric ruins rise from a landscape carved by the area’s industrial past, and charming mining villages offer hearty welcomes, writes Ed Douglas

Only in late autumn and winter do you get such mornings, a thin cold mist hugging the ground, spiders’ webs smothered in dew, and a low sun straining to burn it off. I was walking a section of the Limestone Way, a way-marked path that winds north from Ashbourne through the White Peak to Castleton. The day would be beautiful, but, for now, the stately ash trees common in this corner of Derbyshire loomed out of the grey like spectral giants.

Just outside the village of Bonsall, I passed through a narrow gate into what looked like a battlefield. Everywhere I turned, there were eruptions in the earth, like shell-holes, an apparently blasted landscape disappearing into the fog at the field’s edge. There was a narrow fissure too, thick with shrubs and a hawthorn heavy with fruit, extending into the distance. Every so often, walking through the wet grass, I came across old concrete railway sleepers laid across a hole to save the unwary from falling in.

All this scarring evidenced Derbyshire’s lead-mining industry, not so very long defunct given that people have been smelting lead here since the late Bronze Age. The Romans, with their passion for lead, mined for it as well; an ingot of Derbyshire lead was unearthed in Normandy. When they left, monks from Repton took control of the industry until the Vikings arrived, and when Danelaw collapsed, it passed to the Crown. By the 17th century, lead was Britain’s second-biggest industry after wool, boosted by demand for musket shot in the Civil War, and employing 20,000 people. Sir Christopher Wren made a point of asking for Derbyshire lead for the dome of St Paul’s.

DEEP HISTORY

Bonsall is no longer a hive of industry, the scars have healed nicely and the village is justly proud of its heritage. Bonsall’s Alamy Town is less than a mile from the mine workings, past a pretty tangle of cottages pinned to the south-facing slope of Bonsall Dale. In the bottom of the valley is the Barley Mow, one of the better-known White Peak pubs, quirky and welcoming, with a warm fire and regular live music. Bonsall captures the very specific and deep-rooted appeal of this corner of England, an appeal that rests not just on its stunning limestone landscapes but also the idiosyncratic culture that grew up around lead mining.

“Lathkill recovered and became one of the prettiest Derbyshire dales”

The landscape is the hook that drags you in. The limestone of the Peak is from the Carboniferous era, formed more than 325 million years ago in a warm, shallow tropical sea. Later buried in sediment kilometres deep, mineral-rich solutions, hot and under pressure, permeated the cracks in the rock, leaving veins – known as rakes – of the Peak’s most common minerals: galena, or lead ore, barytes, fluorspar and calcite. Over time, that sediment eroded away, exposing the soluble limestone. Rivers carved the White Peak’s deep dales and burrowed through the rock, creating a honeycomb of underground channels and chambers.

LONG VIEWS

Above Bonsall, as I crested the northern limit of Bonsall Moor, the country opened out in front of me, offering one of the best views in the Peak District. You look straight up the Derwent valley, which drains the distant gritstone moors of Bleaklow and Kinder Scout. But to the west lies high limestone country seamed with deep dales. The plateau is a patchwork of sheep pasture, cropped close for centuries, white drystone walls set against the emerald fields. The steep-sided dales, often hidden from view, are reservoirs of lush woodland and flowers in spring and summer. The crowded shopping streets of Nottingham and Derby are less than 30 miles away; they might as well be 300.

The combination of long views and secret places makes the White Peak formidable walking country, the perfect place to walk off festive excess before finishing near a cosy pub in a pretty village. Some of the best are associated with lead mining: Bonsall, Winster and Youlgreave, and Monyash, sitting at the head of stunning Lathkill Dale, a national nature reserve with a gin-clear stream full of wild trout. Hidden in Lathkill’s thick ash woods are the ruins of Bateman’s House, a remnant of the dale’s lead-mining industry. Horizontal drainage channels, or soughs, were driven into the hillsides of dales so miners could reach flooded veins of lead ore. Bateman’s was built to house a pumping engine but, despite huge expense, it never ran and was replaced with a water wheel; the mine was abandoned soon after.

What’s remarkable is how Lathkill has recovered and become one of the prettiest Derbyshire dales. Given half a chance, nature quickly reasserts herself. Farmers, anxious to keep their livestock off toxic grass, walled-off abandoned lead rakes. Left undisturbed, wildflowers took over, particularly ‘metallophytes’, which thrived on spoil heaps laced with heavy metals, such as leadwort – acushion-forming species with a profusion of white flowers in the summer – and alpine penny-cress. Both species are almost absent elsewhere. Abandoned rakes are a haven for all sorts of species: moonwort, autumn gentians, kidney vetch and several rare orchids.

By the time Thomas Bateman was working as the mine agent in Lathkill, lead mining in the Peak was in decline; competitors got cheaper while the Peak’s untapped veins became harder to reach. The industry’s real social impact had come earlier and is best understood in the fields outside Bonsall, in that moonscape of craters. Here, the lead ore was close to the surface and easily extracted by a man using simple hand tools. The Crown owned most of the mineral rights but anyone had the right to stake a claim – whoever owned the land – as long as the Barmote Court, set up in 1288 to regulate the industry for the Duchy of Lancaster, gave its approval.

RISKY BUSINESS

Local people, often mired in poverty, thus had a licence to dig for buried treasure. Many were farmers, too; the fields around Bonsall are full of beautiful barns, some now restored, others sadly dilapidated. These part-timers made a little extra cash but the rewards of finding a rich new vein were motivation enough to keep looking, captured in the names locals gave their mines: Get It and Make It; Ready Money; Fill Pocket; Luckin-a-Bag; Golden Purse. The risks could be high; Daniel Defoe wrote of seeing a miner emerge from underground, his face pale, black bags under his eyes, classic symptoms of what was known in Derbyshire as ‘bellanding’, or lead poisoning. There was the threat of floods, or falls, or loose blocks crushing heads.

The wealth lead generated is on display in nearby Wirksworth, a market town full of character. The parish church, St Mary’s, is one of Britain’s oldest Christian centres. Set in a wall in the south transept is a simple Saxon carving of a miner with his pick and ‘kibble’, the basket used to carry ore. The carving, originating in Bonsall, is dubbed the ‘t’owd man’, a term that can mean a miner, or the industry – or the ancient underground spirits that had to be placated with offerings of food. Across the nave is the ornate tomb of Sir Anthony Gell, who died in 1583 having founded a local grammar school, and whose family made a fortune from lead.

Wirksworth is also home to the 700-year-old Barmote Court, which adjudicates on lead-mining issues. The court meets once a year at Moot Hall on Chapel Lane, these days for ceremonial purposes, although in 2014, Vicky Turner, owner of Treak Cliff Cavern, applied to the court to claim the lead-mining rights, to prevent anyone else interfering with her business of showing tourists around. The court sat in session before the ‘freeing dish’, a wooden bowl two foot (61cm) long and six inches (15cm) deep, a standard set during Henry VIII’s reign, filled with lead ore. Then the applicants received, as custom dictates, bread, cheese, ale – and a miner’s clay pipe with tobacco. Moot Hall was packed to the rafters; it’s clear there’s life in ‘t’owd man’ yet.

The survival of the Moot Hall is just one more reminder that while visitors might consider this countryside to be prime walking country, the industrial past not only shapes the landscape, but also the culture of the Peak District – and the place is all the richer for it.

Ed Douglas writes a Peak District country diary for The Guardian and his book Kinder Scout: The People’s Mountain was published in 2018.

A keen climber and walker, he lives in Sheffield with his wife Kate, a science journalist.

THE HAUNTED MINE

The chimney and engine-house of Magpie Mine stand like sentinels on the skyline 320m above sea level and a few hundred metres from the village of Sheldon. The last lead mine in the Peak District, Magpie closed in 1958 and its buildings and workings are the best preserved site in Derbyshire. The mine cottage is now a field centre for the Peak District Mines Historical Society (pdmhs.com/). You are free to wander round the site, but at weekends there is often someone there to provide visitors with information.

Many locals considered Magpie to be cursed, even haunted, largely thanks to a nasty feud in the 1830s. Miners from Magpie were in dispute with those from their neighbours at Maypitts and Redsoil and, in 1833, lit a fire underground to smoke them out. Three Redsoil miners died from smoke inhalation and six Magpie men were arrested but found not guilty under a technicality. The three Redsoil widows cursed the mine, which suffered a sequence of floods and fires. Since then, restless spirits have been reported.

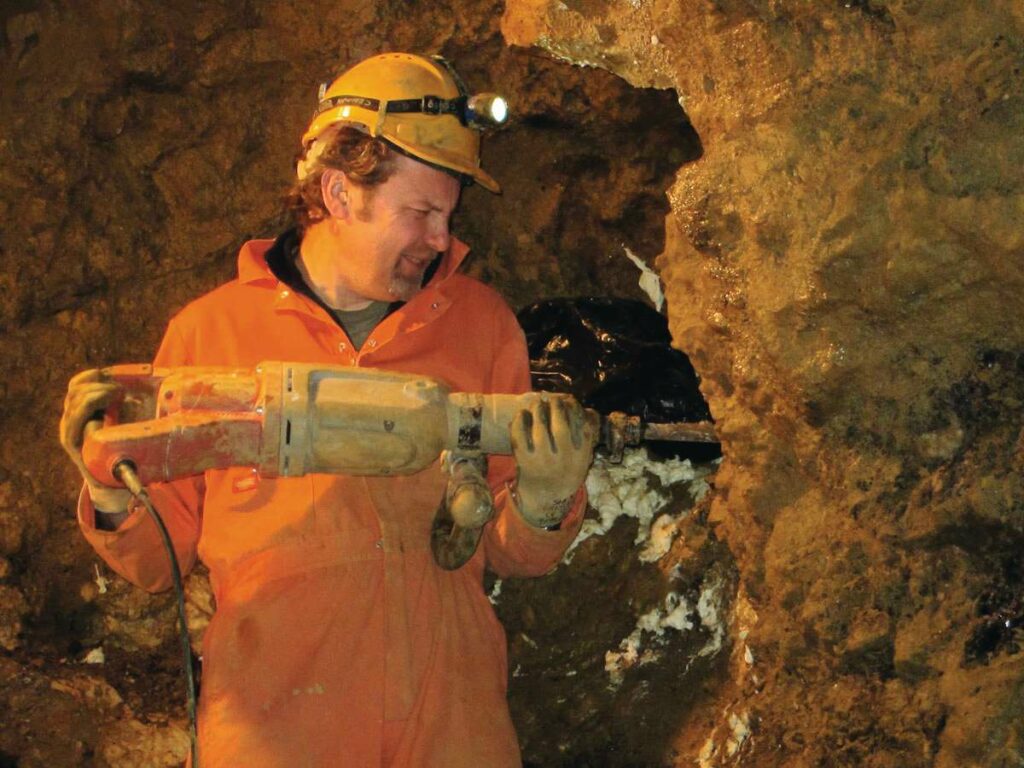

A PEAK LIFE

Gary Ridley has worked at Treak Cliff Cavern, a show cave above Castleton, for 16 years and is looking forward to the festive season, but not for the usual reasons. “It’s very quiet over the Christmas period,” he tells me, “so we shut the cave to visitors and explore for new veins.” Gary is after the valuable mineral known as Blue John, a corruption of the French ‘bleu jaune’, a delicate and pretty fluorite. The stone is graded on site, with some going to jewellers and some made into bowls and jewellery in the cave’s small workshop, with stunning views down the Hope Valley. But before he goes treasure-hunting, Gary welcome the carol singers who gather each winter for a series of concerts by candlelight inside the cavern.

NOW GO TO THE PEAK DISTRICT

Where to stay, eat and drink by Ed Douglas

STAY

Ilam Youth Hostel

There can’t be many ways to stay in a 17th-century Gothic manor for peanuts, especially one so close to beautiful Dovedale, but Ilam Youth Hostel lets you do just that. The grounds are stunning and there are private and family rooms as well as dormitories. yha.org.uk/hostel/ilam-hall

T’owd Man’s Cottage

Paying homage to the area’s mining heritage in its title, this one-bedroom, mid-terrace stone cottage in Bonsall makes a cosy getaway for one or two people keen to explore the Peak District and the nearby High Peak trail. cottages.com/cottages/towdmans-cottage-uk34091

The Stone Estate

Close to Ilam is the lovely village of Alstonefield, a great base to explore Lathkill Dale. The Stone Estate has 10 self-catering cottages in the area, ranging from beautiful barn conversions to charming cottages, all built from the limestone of the White Peak. thestoneestate.co.uk

CAFÉ

Village Green café

The village of Eyam was once a lead-mining centre, although its popularity now rests on the legend of its self-imposed quarantine during the plague outbreak of 1665. The sunny Village Green café has a mouth-watering afternoon tea menu, with a cup of spiced citrus tea to warm you up, and a beautifully presented selection of sandwiches, all-butter scones with strawberry and Champagne jam and a selection of treats. cafevillagegreen.com

QUIRKY MUSEUMS

Now a World Heritage Site, Derwent Valley was a cradle of the Industrial Revolution. Richard Arkwright opened the first water-powered cotton mill at Cromford in the 1770s. In Matlock Bath, Arkwright’s showpiece Masson Mills is the grandest example of his entrepreneurial zeal and has a textile museum. massonmills.co.uk

Nearby is the Peak District Lead Mining Museum, which boasts a real lead mine and a beautiful mineral collection. peakdistrictleadminingmuseum.co.uk

MUST-TRY

Bakewell Puddings

As everyone knows, it’s not a tart, it’s a pudding, but don’t ask Bloomers of Bakewell for their recipe. The café dates to the 1600s but the recipe originates, according to legend, in the 1820s when the landlady of the nearby White Horse Inn – now the Rutland Arms – asked the cook to make a jam tart and instead of stirring in eggs and pasted almond into the pastry, she smeared them on top, under the jam. Thus was heaven chanced upon. bloomersofbakewell.co.uk

PERFECT PINT

Run by earthenware potter Geoff Fuller and his wife Pat, the Three Stags Head in Wardlow Mires holds a special place in Derbyshire’s affections. It’s basic: open fires, flagstone floors, whitewashed walls, impromptu folk music, great cooking involving game and excellent beer from Abbeydale. Dogs are welcome and you might see a hawk, too. Look out for the stuffed, and armed, fox in the window. Open weekends only. 01298 872 268

SHOPPING

There’s a vibrant mix of shopping in the Peak, from family-owned locally sourced butchers and bakeries, to farmer’s markets and specialist shops.

Wirksworth Farmer’s Market

Held on the first Saturday of the month, this market offers wonderful fare from producers all based less than 20 miles from Wirksworth. wirksworthfarmersmarket.com

David Mellor Country Shop

This dog-friendly shop in Hathersage stocks the finest British rural crafts plus designs from international manufacturers. davidmellordesign.com/shops/hathersage

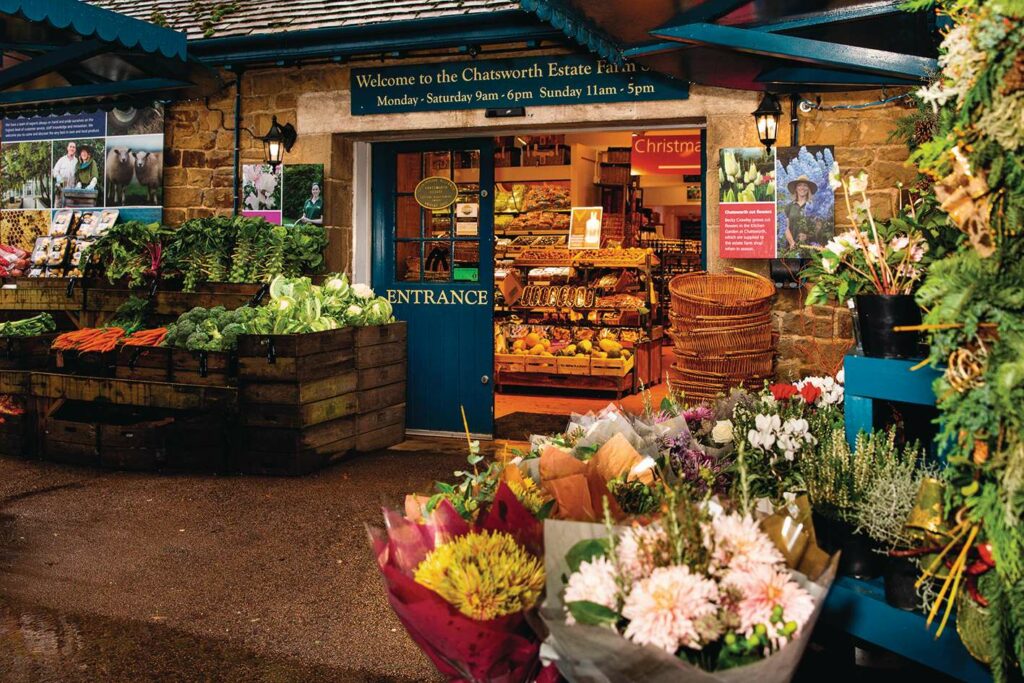

Chatsworth Estate Farm Shop

Find fresh fruit and vegetables, delicious pastries, meat, fish and tempting cheeses at this well-stocked shop on the estate (above). chatsworth.org/visit-chatsworth/shop-dine/farm-shop

THREE GREAT WALKS

Walks around Bonsall

Bonsall’s local history group has produced six leaflets featuring walks around the village, varying in length from 1.3 miles to five miles, which explain the local lead-mining landscape. The leaflet sets are available for £5 from local pubs, B&Bs or Bonsall History Group. bonsallhistory.org.uk

Chelmorton, Taddington and Flagg loop

The five-mile triangle that joins the villages of Chelmorton, Taddington and Flagg offers great walking in the high limestone country of the White Peak. Admire Chelmorton’s medieval field systems and a golden locust on the church steeple. There’s also a short detour to a Neolithic tomb at Five Wells.

Lathkill Dale loop

This epic 10-mile, five-hour walk follows Lathkill Dale from Alport towards Monyash, turning left up Fern Dale and then back across the fields, crossing Cales Dale on the Limestone Way before dropping down to equally beautiful Bradford Dale to Youlgreave and back to Alport, where the two rivers meet.