Hope for Eden?

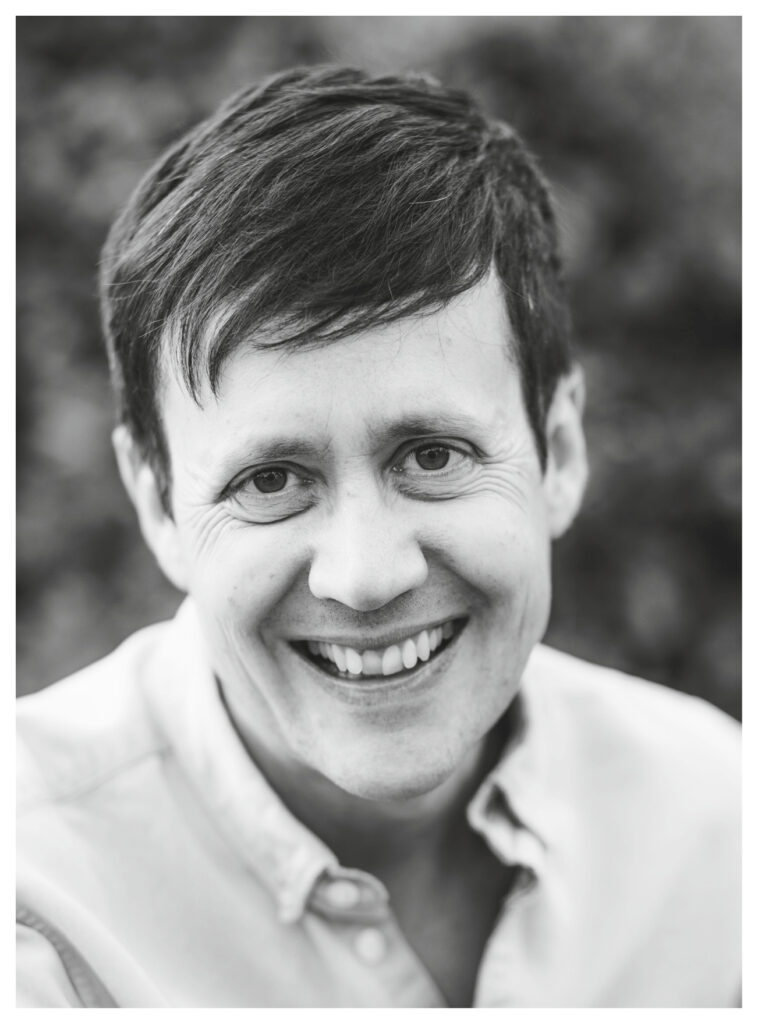

The BBC’s stunning new series Wild Isles reveals that nature flourishes in Britain’s wonderfully benign conditions: rich seas, varied geology and a kind climate. Despite the devastating setbacks of recent decades, these natural advantages offer good prospects for the future recovery of wildlife, writes Patrick Barkham

There is a nation of snow-capped mountains that contains more golden eagles and red deer than any other in Europe. It’s also a haven for nearly half the entire continent’s population of seabirds. Another part of this archipelago boasts most of the world’s chalk streams, which flow through flowery downland home to more large blue butterflies than anywhere else on the planet. These islands are home to a bewildering array of habitats, from temperate rainforests to pine woods usually found in the high Arctic, vast lowland estuaries and purple-hued heather uplands.

Keen to visit this remarkable place? The good news is we don’t have to travel far. This is the British Isles, and they are wilder than many of us imagine.

We are probably familiar with the uncomfortable facts about home: it is one of the most nature-depleted countries in Europe, densely populated, intensively farmed, polluted and still losing both abundance and rare species – at least 500 extinctions, and counting.

All this is true and yet, seemingly against all odds, there remains eye-opening biodiversity for us to discover, enjoy and protect. Such a relatively small area of land at such a northerly latitude would not necessarily be so blessed, but the fact that Britain and Ireland are islands is the key to their natural wealth – and their vulnerability.

“The fact that Britain and Ireland are islands is key to their natural wealth – and vulnerability”

RARE GEOLOGY

There are four reasons for our wealth of wildlife. The first is that our islands are extremely geologically diverse. The gneiss rocks in north-west Scotland and parts of Wales and Ireland are 2.7 billion years old and once formed part of an entirely separate continent, dividing from the land that ultimately made up Britain’s south-east by 4,500 miles of ocean.

Over millions of years, other rocks were created. Warm tropical seas of ancient times were home to a blizzard of marine life whose skeletons were gradually laid down as chalk and carboniferous limestone hills. Such varied geology gives rise to a range of soil types and specialist plants. Springs within the chalk have formed streams that feature unique aquatic plants and animals: around 85% of the planet’s known chalk streams are found in England.

RICH SEAS

The second reason for the diversity of wildlife is our islands’ geographical position on one of the largest continental shelves in the world. We are surrounded by a large expanse of shallow sea – and shallow sea is rich in marine life. Ocean currents, weather systems, storms and some of the world’s biggest tides mix nutrients into the water column.

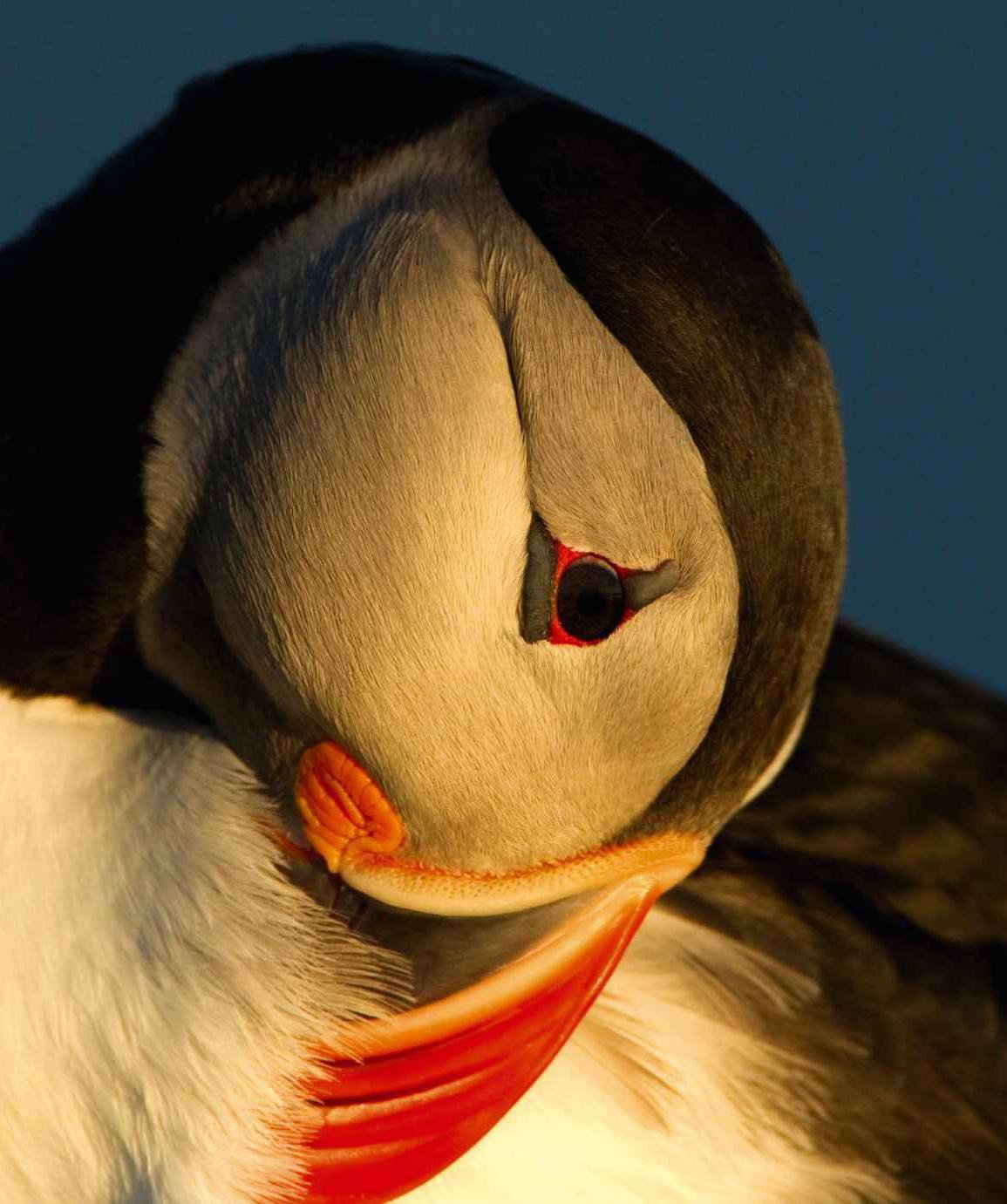

Warmed by spring sunshine, these nutrient-rich waters give rise to fantastic blooms of phytoplankton, microscopic plants that float in the water. Zooplankton, tiny animals and the offspring of much sea-life, feed upon these plants. Small organisms support a grand array of life: from modest scallops and cuttlefish to massive basking sharks and those seabird millions. Our isles are home to 90% of the world’s Manx shearwaters, 60% of great skuas and 65% of northern gannets.

A LONG AND RUGGED COASTLINE

These birds also benefit from the secure nesting sites found on our diverse and unusually long coastline, with plentiful rocky – and mostly predator-free – cliffs and islets. The coast of Britainalone is longer than India’s and itscomplexity supports a great range of life. Intertidal mudflats, for instance, remain unfrozen in winter and so provide a buffet of shellfish, worms and other invertebrates for vast flocks of waders, such as knot, which overwinter on our shores.

The final reason for our wild riches is our hospitable, temperate climate. Britain and Ireland are mild countries, with temperatures above the global average for their latitude. Cool winters are followed by warm summers with few of the temperature extremes found on continental landmasses.

The gentle warming that keeps our winters relatively mild is provided by the Gulf Stream, sweeping in mild weather – and rain. These conditions have created a suite of Atlantic species and temperate rainforest: half the world’s bluebell woodlands are found in the British Isles. And yet there is also a gulf between the weather in the far north and extreme south: contrasting near-Arctic and near- Mediterranean conditions allow a wide range of plants and animals to flourish.

Of course, the species that has prospered most on these islands is homo sapiens. We’re here because these wild riches – plentiful fish, mammals and a verdant growing season – are here. But the early industrialisation of Britain, its large human population and the post-war intensification of farming to feed us has created challenges for wild species. Some have thrived alongside us; badgers live more densely in Britain than anywhere else in Europe because our mixed farms with earthworm-rich pastures and autumn crops such as maize provide welcome sustenance. Now persecution is lessening, many birds of prey are recovering their populations. Peregrine falcons take up residence on cathedral spires and other tall buildings – cityscapes mimicking the clifftops where they lived in the past.

MARINE MARVELS

It is sometimes said that our underwater worlds are less well-known than space. Few of us realise that often ostensibly grey British waters conceal great colour and charisma. Precious seagrass beds are home to the short-snouted seahorse and long-snouted seahorse. During the breeding season, a male and female seahorse form an apparently monogamous bond – by dancing together. The tompot blenny (pictured) is a colourful little fish found in some rockpools. The territorial males meticulously clean rocks on which the females lay eggs. Big fish are returning, too, none more thrilling than bluefin tuna – a speed-demon that hunts herring and mackerel by sight. It vanished in the 1960s but has returned to south-west seas in recent years.

NATURE IN PERIL

Unfortunately, more species are struggling to adapt to our human-dominated islands. Land-use changes – particularly more efficient farming – have destroyed 98% of flower-rich wildflower meadows in England and Wales since the 1930s. More than half our ancient woodland has been obliterated in that time. Britain’s forest cover of 13% (much of which is not particularly nature-friendly nonnative plantation trees) is one of Europe’s lowest. Currently, no single river, lake or coastal water in England is judged to be in a “good” state (both chemically and ecologically) by the Environment Agency.

The creatures that once lived in this habitat have gone too; since 1970, more than half of Britain’s farmland birds have disappeared. A quarter of mammals are endangered and three quarters of butterfly species have declined. Most alarmingly, this dramatic loss of biodiversity has accelerated in the last decade, as overfishing, chemical farming and sewage spills continue, and climate change starts to bite.

“We are surrounded by a large expanse of shallow sea – and shallow sea is rich in marine life”

HEALING EDEN

These challenges are huge, but it is still possible to save wildlife. We can all play our part, whether lobbying politicians to clean up our rivers or joining local beach cleans. Restoring sea-life seems particularly daunting, but a small group of islanders on Arran began a campaign to protect a short stretch of coastline in Lamlash Bay in the 1990s. The campaign blossomed and, in 2008, Lamlash Bay became Scotland’s first marine protected area to be closed to all fishing. Today, marine life inside the reserve is flourishing and cascading into the surrounding Firth of Clyde. Ultimately fishers will benefit too.

If we feel despair, the antidote is local action – wherever we live, there will be a vibrant group nearby managing habitat for wildlife or planting trees or creating new pocket nature reserves in neglected urban spaces. These groups just need our help. Consuming less or making careful choices over everything from our investments to what fish (if any) we eat can have a positive impact too.

WILD WISDOM

Sir David Attenborough brings the Wild Isles TV series to a close by spending time with puffins on the Welsh island of Skomer. Puffin numbers have been increasing on Skomer, but this is an exception: most are in decline because of overfishing and climate change. “It is a clear example of just how fragile and fragmented our nature is,” says Sir David. “Because this is our home, it can only be our responsibility to restore and protect our wildlife. Perhaps you can be the first to pass these wild isles on to the next generation in better shape than you inherited it?”

Must-see

Sir David Attenborough showcases Britain’s wildlife in Wild Isles on BBC Two from Sunday 12 March.

Patrick Barkham is natural history writer for The Guardian and the author of books including The Butterfly Isles and Badgerlands. With Alastair Fothergill, Patrick is also the co-author of Wild Isles, the book on the new BBC series, which tells stories of the wildlife of Britain and Ireland. Featuring images from the series and from leading wildlife photographers, it is published on 2 March (William Collins, £25).

ROCK WONDERS

Areas of limestone geology and thin soils give rise to great floral riches. In the Yorkshire Dales, bird’s-eye primroses grow on limestone pavement, while the moist conditions in the crevices allow lush ferns and shade-tolerant woodland plants to flourish – from hart’stongue fern to enchanter’s nightshade. Gently grazed wildflower meadows may feature autumn gentian, while the rare lady’s-slipper orchid is thriving thanks to conservation efforts. Floral abundance gives rise to a diversity of insects – the Morecambe Bay limestones are an English stronghold for the high brown fritillary butterfly and the northern brown argus.