Art of a dale

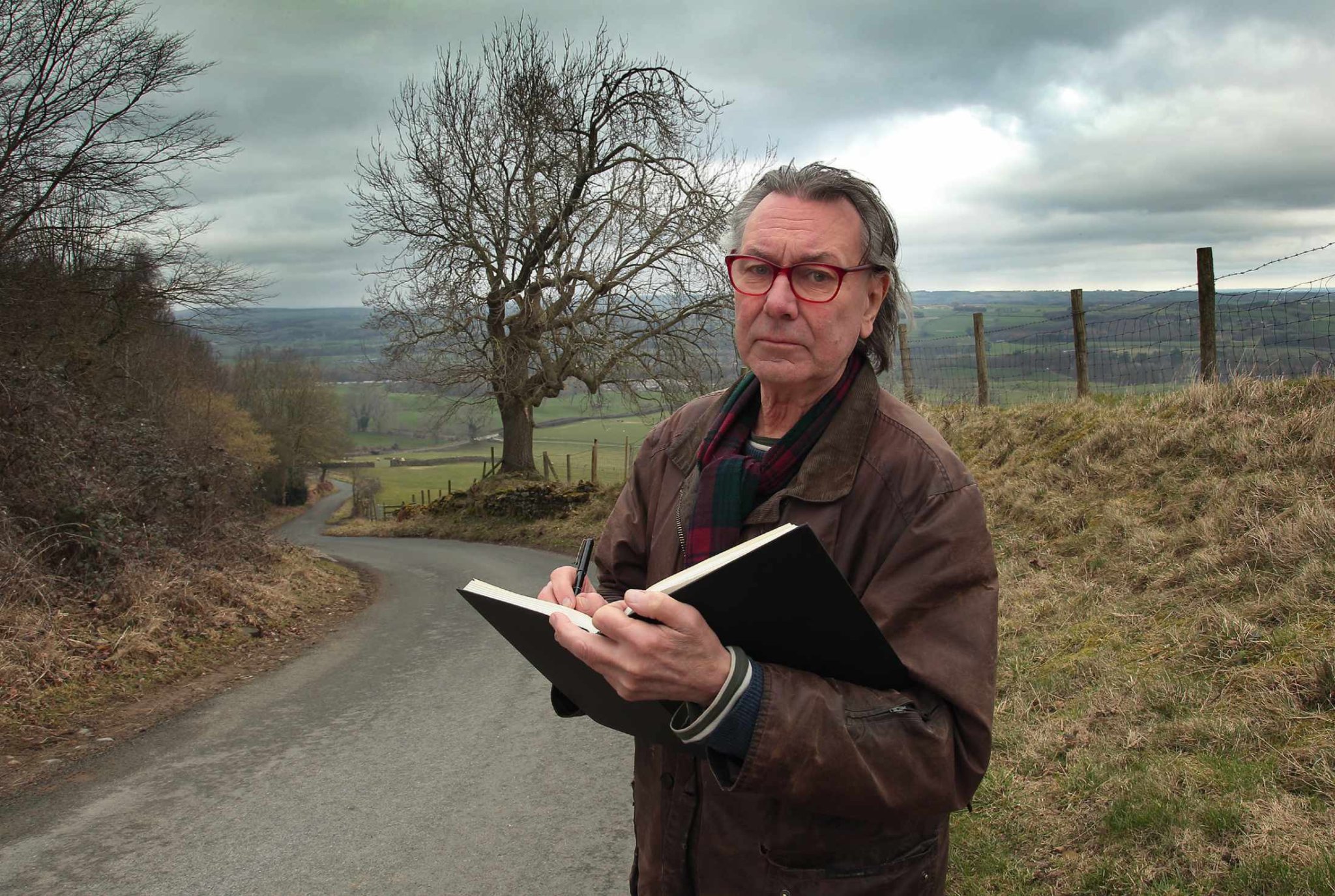

The trees, lanes and green pastures of Wensleydale have inspired Yorkshire artist Simon Palmer for 40 years. Susie White talks to the watercolourist about his spiritual connection with the landscape

The landscape of Lower Wensleydale is one of narrow lanes that swoop and curve following the swell of the land. Bordered by drystone walls and fences, they cross rivers on old stone bridges or undulate between flail-cut hedges and ivy-covered trees. Close by are the moors, where curlews cry and sandy tracks lead among the heather. This is the landscape that has inspired the work of Simon Palmer, one of Britain’s leading watercolour artists.

Simon has lived in a village near Masham for 30 years. He was born in Yorkshire in 1956, his dad a railwayman, but the family moved to south London when he was eight months old. Somehow though, Yorkshire was always in his blood.

“When you’re growing up, you don’t realise how alien you can feel to an area,” he says. “I was depressed and claustrophobic in London. Then I went to Reigate Art School to do a Graphic Design and Illustration course. An important moment was when the tutor encouraged me to go out into the countryside and draw.” While staying with friends in a cottage in Lastingham in 1976, Simon fell in love with the landscape of North Yorkshire. His etchings were selling well and he was able to move up north, where he tried living in different valleys, including Teesdale in Durham, which he found beautiful but bleak. At last, he discovered this corner of Wensleydale. He says that when he saw his current home in the village, set in its agricultural, slightly domestic landscape, he thought “This is it!” And it was there that he met his wife Tink, who lived in a nearby village.

LIFELONG CALLING

Since leaving art school in 1977, Simon has always been an artist, never having another job. Every weekday he works in his studio, a converted garage next to the house. His routine is to read fiction for an hour before starting in the studio at 10am and working until 7pm, with a half-hour break for lunch with Tink. The walls of his studio are covered in postcards and prints. There’s an Eric Ravilious calendar, images of Paul Nash paintings, photographs of landscape and chalk-cut hill figures. Shelves sag under the weight of sketchbooks and books about art.

At weekends, Simon gardens, having created a lovely sloping cottage garden from scratch. Grass paths wind between borders and there are places to discover, to the delight of the grandchildren. With a large pond and relaxed feel, it attracts wildlife and Simon plans to introduce more wildflowers. It is the landscape around the village, though, that provides material for his art, carrying on the tradition of English pastoral painting.

Simon has started on a new painting that is taped on to a sloping board beneath an Anglepoise lamp. To his right is an open book with a drawing that he is working from, one that was done in a few minutes while sitting in his Land Rover. It has a loose, free quality but the essential elements of the layout are there: the verticals of tree trunks, the bend in a lane, the curve of a wooden fence. With no computer or mobile phone, Simon has no distractions while working. “I don’t miss them,” he says, “but I do listen to Radio 3.”

TIME-HONOURED TECHNIQUE

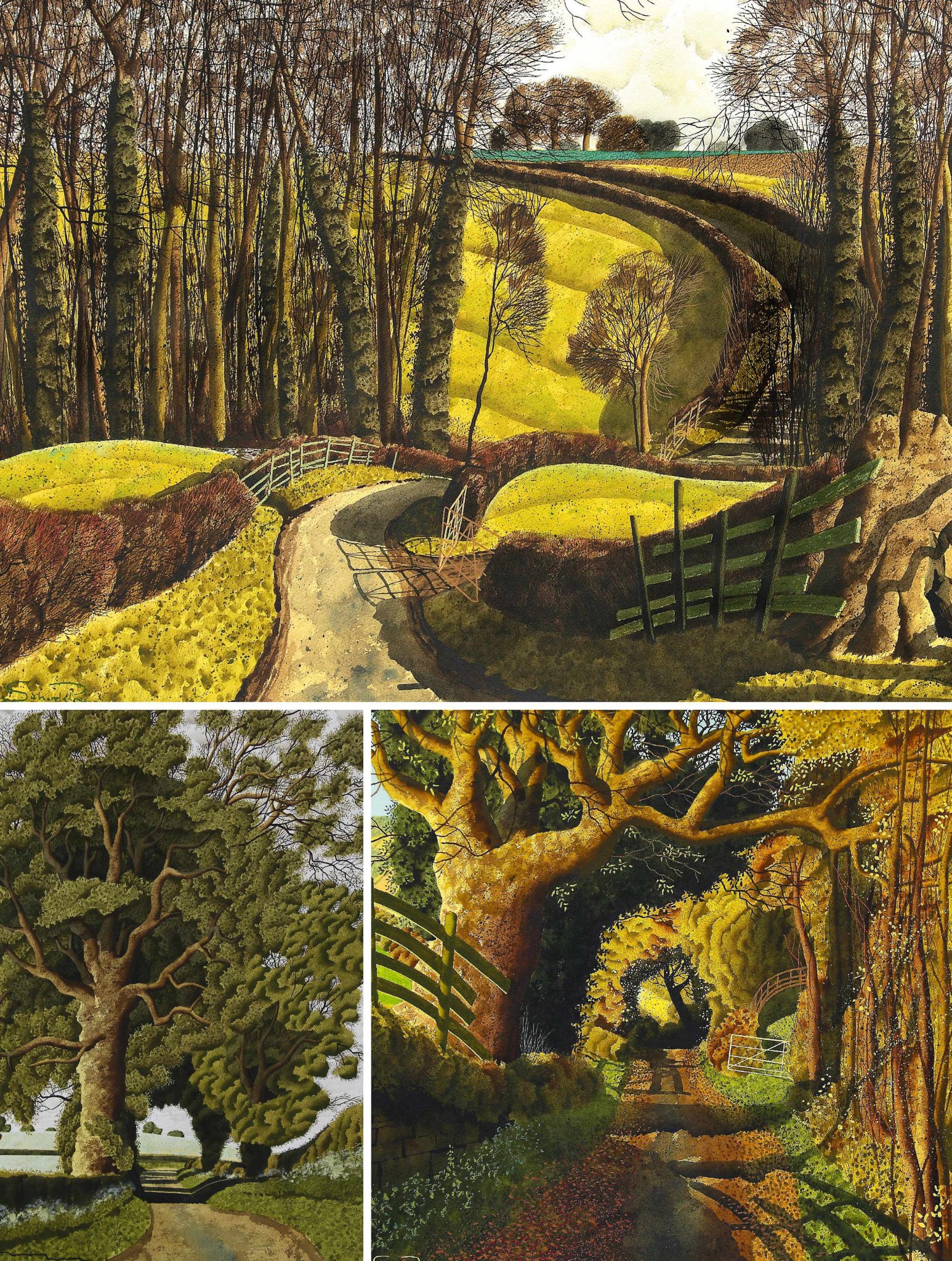

“The paper I use – Arches 610 gsm 100% cotton paper – is heavy enough not to need stretching,” he explains. “I apply a creamy yellow wash over the landscape area, leaving the sky white for vibrancy. I draw first in pencil, then in pen and ink before rubbing out the pencil marks.” Next he adds layers of watercolour; some, in areas such as the trees, using dry-brush technique. It is in the way that he uses pen in the drawing of foliage that you can see the influence of Victorian landscape painter Samuel Palmer, as well as the early engravings of Graham Sutherland.

Simon says he has a photographic memory and can absorb information as he walks. “I couldn’t work from photographs. The lens is deceiving and plays tricks with what you see. At art school I was given a camera with a wide-angle lens. It helped me to see the landscape and accentuate the perspective, and I do that automatically now.”

There’s a particular quality to the countryside in this part of Yorkshire. “The area near Masham is neither lowland agricultural nor Pennine bleakness,” says Simon. “I love geography and this area is classified as the North Pennine Fringe. I call it the estuary of Wensleydale.”

He is fascinated by place names and finds that maps are a great help in coming up with titles for his paintings: Halfpenny Green Lane, Low Thorpe, Swinney Beck Bank. “The names of places can be historic and are often derivations of the Nordic,” he adds. “I love words and I write as well.” Simon trained as an illustrator but felt that illustrations often come second in a book. To counter this, he turned it on its head by doing the illustrations for his book Pebbles on a Beach before writing the text.

“I want to avoid sentimentality… above all I aim for the spiritual atmosphere of a place”

Simon’s paintings are figurative but not photographic. Semi-abstract, they are a blend of abstraction in the shapes – rectangles, curves, circles – and identifiable features. The colour palette is muted; he says he is more interested in tone and texture than colour. By restricting colour, he creates more impact for a focal point, such as the vibrancy of a red road sign or the emerald glimpse of a distant field. His trees aren’t specific species – they are organic forms of pattern and texture, trunks often swaddled in thick ivy.

HUMAN TRACES ON THE LANDSCAPE

Favourite images recur in Simon’s work. Gateposts topped with finials and entrances leading to unseen driveways, stone bridges and abandoned railway arches. There are mysterious figures in his earlier work, sometimes strange and unsettling, whose stories we want to learn. These visionary figures that appear in the familiar settings of minor roads or woodlands recall Stanley Spencer (1891– 1959), whom Simon says he “worships”. Other influences are the Nash brothers, especially Paul Nash (1889–1946), with his Surrealist view of English landscape.

“I have weaned myself off doing figures and I want to avoid sentimentality,” he says, “but I like to include the human element in the land, the road markings, gates and bridges. Above all, I aim for the spiritual atmosphere of the place.” Look at a Simon Palmer painting and your eye travels around it, following a lane as it curves into the distance, wondering what is around the corner. After a while, you notice anomalies: a faded sign, a shadow from something out of the frame.

A solo exhibition of limited edition prints of Simon’s work, Observation of Landscape, is showing until 11 June at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. “I’m thrilled they asked me to exhibit,” he says. “It’s lovely to be acknowledged in Yorkshire where I have such a sense of spirituality in the landscape. My soul is here. I’d be devastated if I had to be anywhere else.”

There are some artists whose work makes us see the world around us in a new way. Simon finds inner meaning in the landscape, what Paul Nash called “the things behind”. Now, the winding lanes of Wensleydale, the copses and tree stumps, the railway bridges and old stone churches are seen afresh as Simon Palmer landscapes.

Simon Palmer’s work will be on display at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park from 4 March to 11 June.

Susie White is a freelance garden writer, photographer, lecturer and author who lives in the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

YORKSHIRE SCULPTURE PARK

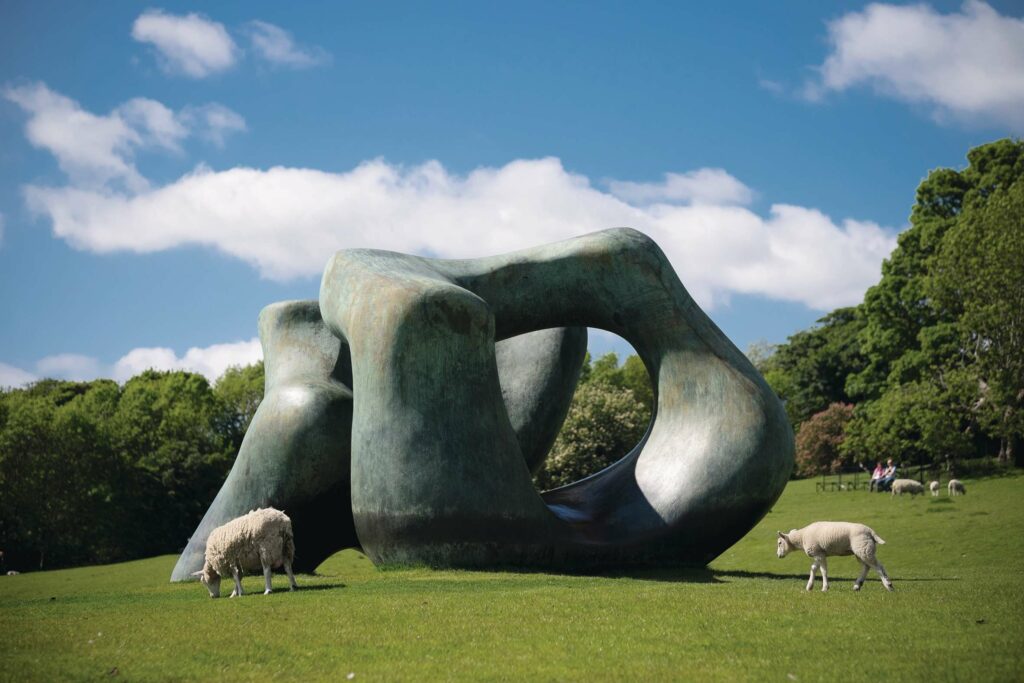

The Yorkshire Sculpture Park – where Simon Palmer’s work is on display this spring – was the first of its kind in the UK. It is also the largest sculpture park in Europe, sitting in 202 hectares of parkland at Bretton Hall in West Yorkshire. This ‘gallery without walls’, founded in 1977 by Sir Peter Murray, is a thrilling place to see art in a beautiful 18th-century landscape, with its woodlands, follies and lake.

There are some 100 sculptures and installations to discover in this exciting open-air collection, with a changing programme of temporary exhibitions. Worldwide artists include Ai Weiwei, a Chinese artist and activist, whose Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads represent the 12 animals of the Chinese Zodiac. Shadow Stone Fold is by British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy, the rectangular drystone-walled enclosure based on the sheepfolds of Scotland and Cumbria. Another work by Goldsworthy, Peter’s Fold, is built around a parkland lime tree.

There is work by 20th-century artists, such as Elizabeth Frink, Juan Miró and Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore’s abstracted forms inspired by animal vertebra or lumps of flint. Moore visited the park in 1979 as its first patron and there has been a display of his works there ever since, the rolling hills and expansive vistas being an ideal setting for his monolithic sculptures.

Location-triggered work based on sound creates a multi-sensory experience as you walk around the park. By downloading an app, you can experience The Poacher’s Lament and Other Half Heard Tales by Dillan Marsh and Eleanor Clare. This is inspired by the history of the park and traditions of folk tales and song.

Currently on show are four major sculptures by Damien Hirst: Charity, Myth, The Hat Makes the Man and The Virgin Mother. In a former deer shelter, James Turrell’s Deer Shelter Skyspace offers somewhere to sit and revel in the changing light and clouds as you gaze up at the sky through a square opening.

There are indoor exhibition spaces, such as the Bothy Gallery and the Underground Gallery. On display until June is Stitched Stories by textile artist Andi Walker, whose hanging quilt represents the stories of visitors to the park. This is just a small flavour of the wide range of media and artworks, as well as workshops and events, that can be experienced indoors and out in the world-renowned Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, Wakefield WF4 4JX.

Open daily; standard entry costs £9. ysp.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions