OPINION

Nicola Chester

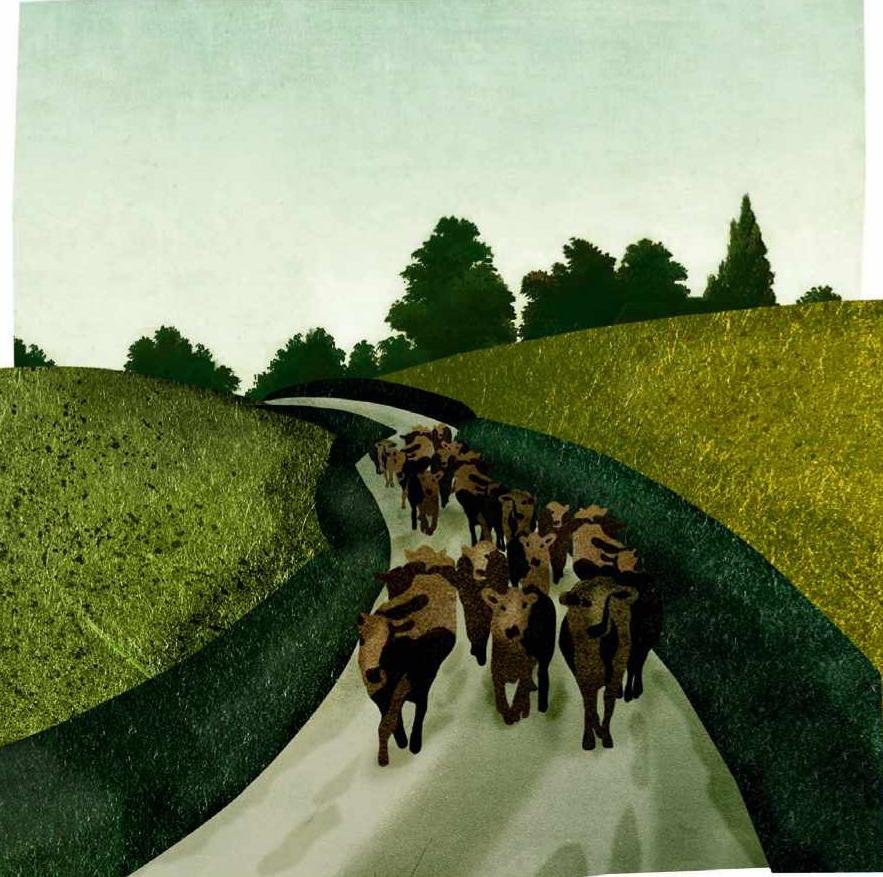

Wandering cows, potholes and unnamed lanes can turn rural roads into a test of patience

“I am lucky to live 15 minutes or so from work. The road there – being pavementless, winding, narrow and highhedged – is not safe enough to walk or cycle on, and though there are footpaths to get me there, they take an hour and a half. There is even a village bus, though not one regular enough for my hours.

It’s a beautiful route, through the North Wessex Downs in Berkshire, and though there’s never any traffic, I’m rarely short of reasons to be late. Patience and gritted good humour are the only ways to deal with rural delays, unless it falls upon you to take action. This applies if the cows on the common are walking in a long column down the middle of the road, or lying on it. We are all pretty skilled in delivering a cheery, encouraging clap on the rump to move them on. The exception to the rule occurs only on the way to school with a new bus driver, when each pupil denies knowing how to move cows, then remembers at home time.

Road closures are frequent and often a surprise, and those that are planned seem not to have a cone, nor any works started on them for weeks. This puts us all in a spin, until someone puts the closure sign against a hedge. Sometimes, a water leak, a particularly large pothole and a fallen tree conspire to close all the roads out of the village at once, until someone fetches a chainsaw. And at other times, notification of a closure and diversion baffles us all: “The unnamed road, between the junction of unnamed road and unnamed road, past Hell Corner Farm will be closed. Please seek diversions from the unnamed road, to the unnamed road on Rooksnest Lane.” Thank goodness for farm names.

The fact that there are almost no road-name signs in the village is not lost on those of us who know them (and keep the names alive by using them with delight, like sharing a secret code, or by reviving much older names or inventing new ones that catch on) but it does mean visitors can seemingly be lost for weeks. We try to help. One bewildered driver was seeking a church wedding in another village. The quickest route was four short miles along the ridgeway, but I told him he’d likely get stuck. Otherwise, he was 10 wiggly and convoluted miles from his destination. Luckily, he wasn’t the groom.

The name behind Bell Lane was a mystery until recently. It has a name plate at one end and is reputedly the “most-winding road in Berkshire”. But its name? According to a village elder, you could hear bells ringing from carts or traction engines as they approached each blind bend along its length. Now, those bells have been replaced by toots on a car horn, usually from someone really quite lost.

A SLOWER PACE

In 1941, Miss Julia White bought the dilapidated Manor Farm here, and drove from the New Forest towing a small caravan. Aside from unwillingly ending up part of a convoy of tanks, she had trouble navigating because it was wartime and all road signs had been removed. I don’t think they were ever put back. Miss White went on to build a new road of packed chalk in the village, and put in a water supply, that only now, all these years later, is beginning to leak and close the road again.

I like the roads this way, mostly. Anything could be around a corner – astring of fresh racehorses, a flock of sheep, a loose dog, children on bikes and people on foot – and it slows (most) people down. And for those it doesn’t? They will get the Facebook treatment if they are local, and wrong directions if they’re not.”

Nicola Chester is the author of Richard Jefferies Award-winning and Wainwright Prize Highly Commended book On Gallows Down.

Have your say

What do you think about the issues raised here? Write to us or email editor@countryfile.com