Rainforests on our doorstep

When we think of rainforests, the Amazon or the Congo spring to mind, but Britain has its own share, full of wild character, thronging with life and in desperate need of protection. Guy Shrubsole tells the story of these secret forgotten habitats

“It’s hard to appreciate the awe and beauty of a rainforest without visiting one yourself”

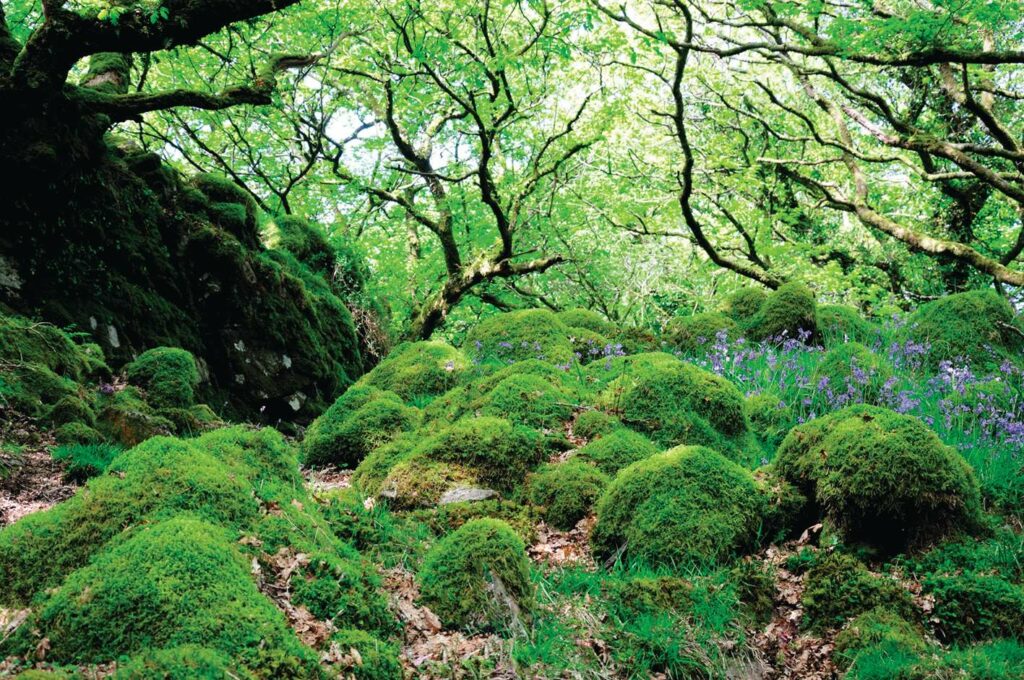

I didn’t really believe that Britain was a rainforest nation until I moved to Devon. Visiting woods around the edge of Dartmoor, in lost valleys and steep-sided gorges, I found places exuberant with life. I spotted branches dripping with mosses, festooned with lichens, liverworts and polypody ferns; plants growing on other plants. I was enraptured. Surely, I thought, such lush places belonged in the tropics, not in Britain.

But it’s true. Few people realise that Britain harbours fragments of a globally rare habitat: temperate rainforest. Rainforests aren’t just confined to hot, tropical countries; they also exist in temperate climates. A temperate rainforest is a wood where it’s wet and mild enough for plants to grow on other plants. Temperate rainforest is actually rarer than the tropical variety: it covers just one per cent of the world’s surface.

The temperate rainforest ‘biome’, or set of ecosystems, is strung across the globe, in areas where oceanic currents bring warm winds and torrential downpours. Rainforests exist along the Pacific north-west coast of the USA and Canada; on Chile’s southern edge; in Japan and Korea; across Tasmania and New Zealand; and along the western seaboard of Europe – particularly the Atlantic fringes of Britain.

As I got used to the idea, it became obvious to me that rainforests belong here. As a country, we’re stereotypically obsessed by our rainy weather. How very British, then, to have rainforests. And, as I was to later discover, half-forgotten memories of our rainforests are woven into our myths and legends, and feature fleetingly in poetry and prose from some of our greatest writers. But why, I began to wonder, have we managed to so comprehensively excise Britain’s rainforests from our cultural memory? Why are even environmentalists unaware of their existence?

It’s hard to appreciate the awe and beauty of a temperate rainforest without visiting one yourself. Their rarity and remoteness mean most people in Britain have probably never seen one. So let me take you on a journey into Britain’s lost, forgotten rainforests.

IN TOUCH WITH THE SACRED

My first, abiding memory of visiting one of Britain’s rainforests is how lush and green it all was. All woods are green in summer, of course: but our rainforests are green all year round, due to the plethora of mosses and lichens clinging to their branches. Even when the leaves have fallen from the trees, they glow with a verdant luminosity. I remember the earthy smell of fungus and leaf mould, the distant roar of a river in spate, the drip-drip of falling rain.

A visit to a rainforest feels to me like going into a cathedral. Sunlight streams through the stained-glass windows of transluscent leaves, picking out the arches of tree trunks with their haloes of moss. They’re places that at once teem with life and yet have a sepulchral stillness to them. Small wonder the Celtic druids once revered them as sacred groves.

The trees that make up Britain’s rainforests are both familiar and strangely alien. The mainstay of our wet Atlantic woods are oak trees. Yet they’re quite unlike the tall, straight oaks of lowland England. By contrast, our rainforest oaks tend to be stunted and small, windblown and gnarled – hunched low to the ground to withstand the Atlantic gales, their roots clutching at the thin upland soils.

The limbs of these magical trees are often bent and contorted into outlandish shapes. In their winding trunks, a thousand imaginary faces glower; their twisted branches the stuff of fairy tales. Out of their boughs have sprung legends of ghostly hounds and horned hunters, green men and pixies.

Oaks aren’t the only species of tree in our temperate rainforests. They also teem with holly, birch, rowan, hazel and ash, the species mix of British rainforests varying in different parts of the country. In windswept upland areas, hardy hawthorn does well, its spiky branches protecting it from munching sheep. On wetter ground, closer to streams and brooks, goat willow thrives. In Scottish rainforests, birch tends to predominate, alongside sessile oaks. The west coast of Scotland also boasts some extremely rare ancient hazel woods, dating back thousands of years.

What really marks out a temperate rainforest, however, isn’t the dominant species of tree, but rather the other plants growing on them. Epiphytes – plants that grow on other plants – are a key indicator of rainforest. Epiphytic plants aren’t parasites; they simply use the trees as scaffolding and soak up nutrients from the rain and dampness surrounding them.

In Britain, the most common epiphytes are lichens, bryophytes – a grouping that includes both mosses and liverworts – and ferns. The more lichens, mosses and ferns you can see growing on the branches or trunks of trees, the more likely it is that you’re standing in a rainforest.

Lichens and mosses are small and can be hard to identify; but easier to spot from a distance are the polypody ferns that sprout from Britain’s rainforest trees. These beautiful, delicate plants love the damp shade and humidity of our western oakwoods. The translucent fronds of polypodies lend a furry green aura to each tree they grow on, particularly when sunlight glows through them. ‘Polypody’, meaning ‘many-footed’, refers to the fern’s method of spreading. It sends out horizontal roots called rhizomes that creep along branches, step-by-step, sending up fresh shoots at each interval.

WHERE LIFE THRIVES

Rainforests are home to more than just trees. Their canopies support a rich and diverse bird fauna. Besides the usual species of British woodland birds, our western oakwoods are particularly good habitats for threatened wood warblers, declining pied flycatchers, and the fire-tailed redstarts. One bird in particular is vital to the survival of Britain’s rainforests: the jay, with its blue-and-black striped wing feathers. Its appetite for acorns makes it nature’s chief planter of oak trees. Jays will carry acorns far from their mother tree, bury them in the earth for safekeeping and then forget where some of them have been stashed; the survivors grow into new oaks.

Perhaps so far I’ve given too sunny a description of these rainy forests. Their usual weather, of course, is wet. Really wet. If you’re lucky enough to visit them when the sun’s shining, you’re not really seeing them at their best. For most of the year they drip continuously with moisture, drip from their canopies, drip from every branch and leaf and stem. The rain runs through these woods in streams, along footpaths that become streams in winter torrents. You’ll return from a visit to a British rainforest soaked from head to toe, but feeling all the more alive for it.

“I would find the ruins of abandoned farms and tinminers’ huts carpeted in moss”

While rain brings life, it also brings decay: dead wood rots. But that decay in itself brings forth more life; fungal life. Gelatinous wood-ear fungus spawns from decomposing branches. Giant bracket fungi protrude from rotting trunks, large as dinner plates – their upsides hard like clam shells, their undersides white and fleshy. Most outlandish of all is the hazel gloves fungus, unique to temperate rainforests, whose orange lobes resemble creeping fingers.

Britain’s rainforests conceal other secrets, too. On some of our adventures, my partner and I would find the overgrown ruins of forgotten buildings: abandoned farmsteads and tin-miners’ huts, their tumbledown walls carpeted in moss and enmeshed in tendrils of ivy, like lost Mayan temples.

WHAT HAPPENED TO OUR RAINFORESTS?

The awful truth is that we destroyed them. As Stone Age hunter-gatherers developed agriculture and started settling, they began to clear the Wildwood for farmland with flint axes, fire and browsing livestock.

As stone tools were replaced first by bronze ones and later by iron, hacking down the Wildwood became easier. The zone of destruction also moved from the lowlands to the uplands.

Yet many areas of rainforest escaped the destruction of the Wildwood, surviving into more recent centuries. Some lasted long enough to make their way into the historical record, their after-echoes etched into place names, myths, legends: Wistman’s Wood on Dartmoor, Coed Felenrhyd in north Wales, Keskadale in the Lakes. Some succumbed to medieval tin-miners; some to Victorian charcoal-burners; others to the nibbling teeth of sheep. Unforgivably, some of Britain’s rainforests were destroyed as recently as the 20th century, felled by landowners and the Forestry Commission in the name of timber production. Britain was once a rainforest nation. But we lost most of our rainforests.

A RESTORATION QUEST

I have read every study I could find voraciously, following in the footsteps of those who have explored our rainforests before. But as I went further, the footsteps became fainter to see, the path overgrown.

Why was there no proper map of where Britain’s temperate rainforests survive, I wondered? The more experts I spoke to – the more lichenologists, climatologists and mapmakers I called on for help – the less certain I became that this precious habitat was fully understood.

So I decided to start a blog, ‘Lost Rainforests of Britain’, to try to drum up public support for protecting and restoring these amazing places. I created a Google Map to gather together examples of where fragments of our rainforests cling on, adding locations that my partner Louisa and I had visited. To launch the blog, I put a call-out on Twitter for people to send in photos of potential rainforest sites they had visited, thinking that at best it might generate a handful of new leads.

I was overwhelmed by the response. Hundreds of people sent me submissions for the map, deluging me with photos of the beautiful wet woodlands that they knew and loved; photos of trees covered in mosses and ferns, thriving in hidden valleys and inaccessible gorges up and down the western edge of Britain. My email inbox overflowed with excited messages of support, expressing surprise and delight at the realisation that the woods they had been walking in turned out to be temperate rainforest. A follow-up piece I wrote for The Guardian received over 200,000 views.

We are haunted by a folk memory of the great Wildwood that once covered Britain, whose outlines occasionally resurface not just in our myths but also in pollen cores and fossil evidence. Doing something to repair the damage done to our own rainforests here in Britain – “this other Eden”, this “green and pleasant land”, as our greatest playwrights and poets would have it – feels like a redemptive quest. In restoring them, we might yet restore a missing part of ourselves.

Because our rainforests aren’t irrevocably lost. Fragments survive. And as I was to discover, in some parts of Britain rainforests still thrive. Far from being dying relics from some bygone era, they are living ecosystems – growing, regenerating and spreading, whenever they are given half a chance. As Jeff Goldblum memorably intones in Jurassic Park: “Life… finds a way.”

Guy Shrubsole is a writer and Right to Roam campaigner. His book The Lost Rainforests of Britain is published by William Collins.

FIVE GREAT BRITISH RAINFORESTS TO DISCOVER

Why not set out on a quest to explore a rainforest this year? Visit Guy’s website to discover more locations: lostrainforestsofbritain.org

Lustleigh Cleave, Devon

The site of an ‘accidental rainforest’, this common has spectacularly regenerated over the past century, so that what was once bare moorland is now carpeted with lush woodland dripping with mosses and liverworts.

Ariundle Oakwood, Highlands of Scotland

A glorious old-growth rainforest, abundant with the bright green lichen known as tree lungwort and its blue cousin Lobaria scrobiculata.

White Wood, Dartmoor

This stunning expanse of Atlantic oakwood looks positively Amazonian when viewed from Bench Tor. In spring, enter its depths along the footpath to glimpse pied flycatchers.

Glasdrum, Argyll

Some of the trees here are so heavily garlanded in weird and wonderful lichens you can no longer see their bark. Look out for Collema fasciculare, a jelly lichen that resembles a bug-eyed monster.

Ty Canol, Pembrokeshire, Wales

An emerald jewel of moss-covered boulders and gnarled, dripping trees, people have co-existed with this wood for thousands of years. Look out for the nearby Neolithic burial chamber at Pentre Ifan.