A potted history

Like three generations of his family before him, Dave French makes lobster pots the traditional Devon way – using willow stems. Now he is passing on his skills to an apprentice. Rosanna Morris meets the master and his pupil

Photos: Sean Malyon

Walk along the quay of a fishing village in the UK and you will spot the ubiquitous lobster pot stacked up in huge piles – a familiar sight on harboursides from Tobermory to Clovelly. The creels will mostly be made from a plastic-coated steel frame, with plastic rings, rope and netting. Yet even modern traps have a romance about them – probably because they are the tools of local fishermen, a sight that reminds us that, in some areas, fishing is still thriving.

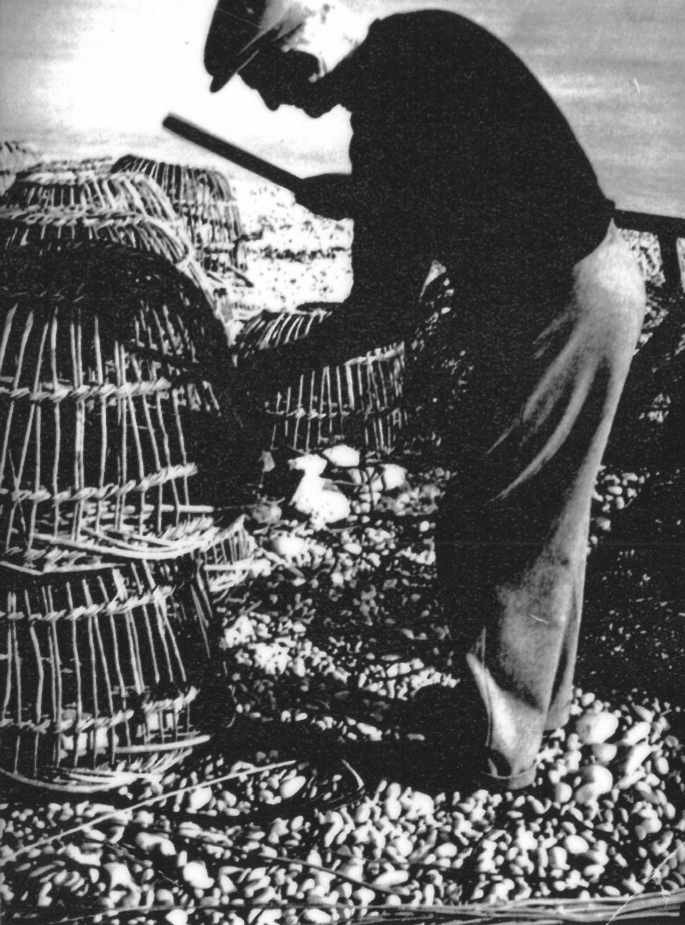

However, these modern pots are not a touch on their predecessors. Study old photographs of the British coastline and you will spy lobster pots constructed from willow. These woven withy pots are particularly beautiful, leading many to view them as decorative remnants of a now obsolete practice. But traditional lobster-pot maker Dave French, based in Plympton, Devon, insists they are as relevant today as they were a century ago – perhaps even more so.

Dave and his apprentice Sarah Ready are on a mission to ensure that not only does this critically endangered craft endure, but that it is a skill mastered by today’s young fishermen and women so they can catch lobsters and crabs in a more sustainable, less destructive way and help the small-scale fishing industry survive. “It is vital to keep this craft alive, especially now with all that is happening with plastic in our oceans,” says Dave. “Sometimes you have to look to the past to figure out where you have gone wrong with things. Fishing is no exception.”

AN INHERITED SKILL

Fishing with woven baskets dates back centuries, although there are no records to tell a true history. Before boats were commonplace and many people could swim, coastal families would catch food from the sea by wading out into low tides with baskets. “I’ve seen a 16th-century painting with one of these pots, but they go back way beyond that,” Dave says.

Dave is from a Budleigh Salterton family with the surname Mears. His grandfather, great- and great-great grandfather were all withy pot makers and lobster fishermen. He grew up watching pots being made and seeing them being used. “The making of these pots was vital if you wanted to catch crab and lobster, as you couldn’t go to a supplier and buy pots back then,” he adds. “Each area of our coastline, where there was a beach or harbour, you would have seen willow pots. The design did vary, of course, as local conditions dictate how robustly you have to make the pots.”

Whereas the lobster pots we know today tend to be rectangular or half-cylindrical, the handmade withy pots are circular, in the form of an inkwell. The fishermen spent January to March making pots, using a stand dug into the ground – one person could make 40 to 60 pots a season – before working the pots out to sea from small boats in the summer.

Willow was grown in and around villages but only in small quantities, so most would come from willow beds. Budleigh Salterton pot makers sourced their willow from the Somerset Levels, some 40 miles to the north-east. “We also used hazel cut from the hedgerows for the outer edge of the base of the pot,” explains Dave.

Everything changed in the 1960s, however. Like many industries, the introduction of plastics and other synthetic materials transformed fishing. Lobster pots could be mass-produced cheaply from plastic and other durable materials. They were also easier to use, which meant more crustaceans could be trapped, as they could be dropped to the seabed in strings of 10 or 15 and hauled up with a winch rather than by hand.

Transport changed life, too. The development of refrigerated lorries meant catches could be transported further and seafood wasn’t just something to be consumed close to the coast. The 1960s also witnessed the Beeching cuts, which saw railway lines close up and down the country, including the line to Budleigh Salterton that brought the withies in from Somerset. While these developments sounded a death knell for this cottage industry, at the time fishing families viewed some changes as progress. “We saw it as a blessing when a new design of pot was created, as it took away the effort and expense of making new pots,” says Dave. “People like my uncle Gerald wanted to leave the old pots in the past.”

“Pots are never perfect. They can be wonky but will catch the same”

But Dave couldn’t leave these pots behind. Because the craft was beginning to be superseded when he was a boy, he didn’t take it up when he was young. When he was 40 (he’s now 65), he noticed the resurging interest in traditional crafts and realised he needed to keep his family tradition going. He is now one of the last makers of working willow pots in the country. “Because I had watched them being made from a young age, I knew the basics,” he says.

WORKING WITH WILLOW

Using thick 2.7m lengths of withy, Dave can weave a pot in around two-and-ahalf hours. He can usually produce 40–60 over a winter when the willow is harvested and green. He stands up as he weaves, using a tall wooden pot stand, on which he constructs the ‘mouth’ first. The top of the stand has holes in it that determine the size of the mouth – usually 20–22 centimetres. “Pots are never perfect,” says Dave. “They can be wonky and lean to one side, but will catch the same.”

The shape and size of lobster pots has evolved over time. “They were taller when my grandfather made them,” says Dave. “It was easier to catch lobster then. The catch has gone down since, so they became smaller and wider.” Different areas in the UK had slightly different pots. If you’re not an expert, pots from Devon, Dorset and Cornwall might look similar, but Dave can tell the difference. “The Cornwall coast has very hard ground, so the bottoms are turned in with much stouter withies to give the extra protection needed. Cornish pots also have a large, upswept mouth and the binders tend to weave anti-clockwise, whereas the rest of the country were more rounded in shape and the binders go clockwise. The East Devon style is a bit of a hybrid pot; it carries the classic Devon shape overall, but the base is turned in from the middle outwards – all other areas of the UK turn the base in from the outside inwards.”

LOOKING TO THE PAST FOR A FUTURE

Sarah Ready (above) and Dave believe that keeping the withy pot craft alive will dramatically help the survival of the small-scale fishing industry, as restaurants seeking artisan producers will pay more for their seafood. Recently introduced legislation and regulations following Brexit and the Covid pandemic, are strangling the livelihoods of local fishermen, who already had to compete against the large trawlers. “Using withy pots to catch their lobsters and crabs will mean they can get a higher price for their catches,” says Sarah.

Dave and Sarah are working with organisations such as Bangor University and Lyme Regis Fishing College with the aim of setting up cooperatives for artisan lobster catching and selling. They are also hoping that growers such as Musgrove Willows, their withy suppliers in Somerset, will make pots and sell them to fishermen. A former lawyer, Sarah has established NUTFA (New Under Ten Fishermen’s Association), an organisation set up to support fishermen with boats under 10 metres long who are making a living from the sea.

TRADITIONAL POTTERY

It was these nuances that muddled Sarah and happily led her to become Dave’s apprentice, funded by the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust. Sarah has lived in Brixham for 25 years and is married to a fisherman. She started researching willow lobster pots about 10 years ago, travelling the West Country and trying to learn how to make a pot, but she was struggling. Dave noticed she was trying to learn several styles at once. “Dave took me under his wing and taught me how to make an East Devon pot,” says Sarah. Sarah explains how she loves working with her hands using a natural material. “It’s amazing to make something that starts as some withies and then you’re catching lobsters with it,” she says. “We’re pushing ahead reviving the craft, but this now rests on a slightly younger generation.”

PASSING ON THE SKILL

Sarah and Dave spend a lot of time teaching others how to make the pots and educating fishermen on the benefits of using them over plastic versions. They use most of the pots they make themselves, but every year they sell about 12 to others, who work them alongside the plastic pots.

“People are much more concerned about sustainability and how the food they eat impacts the environment,” adds Sarah. “Microplastics in our oceans are a big concern. Also, ghost fishing – where lost fishing equipment, including pots and traps, drift through the sea – has a huge impact on marine life. Some plastic pots can keep going for eight years, trapping fish and crustaceans. The willow pots are designed in a way that means creatures can get out. They also biodegrade.”

Sarah also focuses on the issue of food miles. “I have restaurants in London wanting to buy our sustainably caught lobsters but, from my point of view, by the time they are caught, packaged and have travelled 150 miles, it defeats the purpose,” she says. “I want to sell them locally. I don’t want to have to put the catch in plastic containers to travel by courier with gel pads.”

As with many aspects of modern life, it seems that looking to the past and to plants is how we can build resilience for the future, both in terms of protecting our natural world and our livelihoods. The withy pot represents a more gentle way of living in harmony with nature and a more rewarding life for fishermen.

HOW DAVE MAKES A LOBSTER POT

1 “On a typical Devon pot, you start by inserting 12 withies into the top of the pot stand,” says Dave.

2 “Then weave two rods in and out of those 12, adding more until you get a height of between 12 and 15 centimetres – that is the mouth of the pot made,” adds Dave.

3 “Either side of the 12 withies I insert two more withies, so there are 36.”

4 “I then take bunches of three withies and fold these down to create the curve on the top of the pot.”

5 He continues until all 36 are folded down.

6 Dave then places withies into the pot mouth and weaves them over and under the bunches of three, then uses smaller withies to weave spiral binders over and under each withy to keep the shape of the pot. “On a Devon pot, you do four full turns of the binders around the pot to give it strength and form its shape,” he explains.

7 Dave trims all the loose bits.

8 He then takes it off the stand and folds the base in.

Rosanna Morris writes about art, design and craft. She lives in Somerset and can usually be found scribbling or walking her English pointer Elma.