Cumbria’s precious coast

Travellers flock to Cumbria’s fells and lakes, but few visit its rugged coastline. That may be about to change with the opening of a dramatic new stretch of coast path, writes Julie Brominicks

Photos: Dave Willis

The Lakes? Who’d want to go there?” The first coast-path users I meet are local – as will all the others be, save for hikers leaving St Bees on the Coast to Coast Path bound for Robin Hood’s Bay in North Yorkshire. I have pointed out how quiet the Cumbrian coast is compared to the Lake District National Park, just a short way inland. “They’ll be crawling over each other like ants there today,” my new friend from Millom snorts. “And it will cost them a ‘harm and a leg to park.”

His companion pokes him cheerfully with a walking stick before adding, with a sweeping gesture that takes in the Duddon Estuary: “You don’t need a car here. It’s grand! And it’s all free.” I look at the sparkling sea, the bird’s foot trefoil gilding the derelict iron-ore quarry (now a nature reserve), and heartily concur.

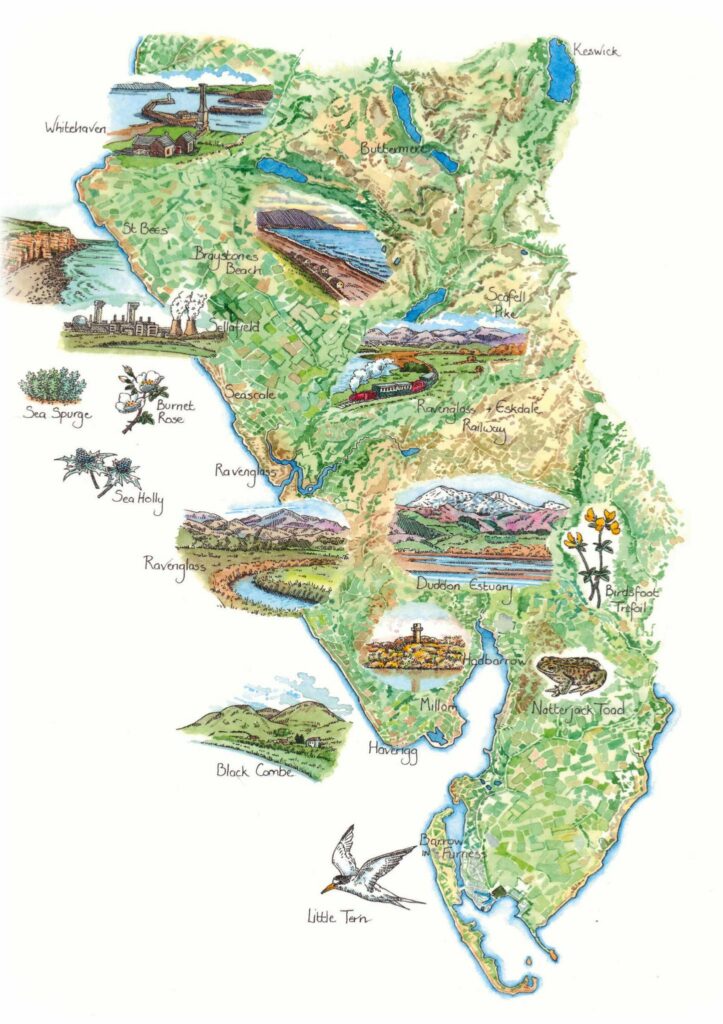

I am walking the coast between Millom and Whitehaven. Offshore is Walney Wind Farm and the Isle of Man, while inland the Western Fells of the Lake District press close then collapse into sheep and dairy pasture, hedged lanes and maritime grassland that sprawls to the shore. Yet the coast is largely ignored by the multitudes who frequent the Lakes. A few come to Ravenglass, the only settlement in the National Park that is also on the coast, to St Bees for the Coast to Coast Path, or to the beach at Seascale, a former Victorian resort. The rest are presumably deterred by mountains, rural roads (unaware of the excellent coastal railway network), weaponstesting ranges, industries and particularly by Sellafield Nuclear Power Station.

Nuclear activity is scaling back these days, while the iron-ore quarry at Millom and Whitehaven colliery have closed. Despite all this activity, the coastal margin includes key habitats for terns, natterjack toads, orchids, adders and auks. Fishermen are out now, digging for worms in channels left by the ebbing tide.

VISITOR VALUE

I raise the subject of tourism with Jade Hughes at Millom Heritage and Arts Museum. “You speak to some people and they don’t want tourists, but we need jobs now the mines are shut,” she says. “It’s about getting the balance right. We don’t want it like Windermere kind of thing, where you can’t afford to buy homes. But we want people to see what we’re doing here, what we’ve got.”

“The coast is largely ignored by the multitudes who frequent the Lake District”

Balancing walkers and wildlife is also important. Dogs need to be on leads in sensitive sites, for example, so as not to stir up silt in pools where natterjack toads breed. The next morning, I find Rachelle Regan counting terns in RSPB Hodbarrow hide. It’s an exciting place, with sandwich, common and little terns zooming to the shingle island with sand eels in their beaks.

“It’s good for people to come and see this,” Rachelle says carefully. “As long as the birds aren’t put under stress.”

Caution is justified. The island, lying in a lagoon that formed in the disused quarry, was extended in 2020 and enclosed by a fence, because terns nesting on the shore were suffering from disturbance by foxes, rats, people and dogs. Now tern numbers have significantly increased. “The little terns nest near the high-tide mark,” says Rachelle. Her telescope reveals ringed plover, an oystercatcher and suddenly, yes – two fuzzy yellow chicks, rising above the pebbles to greet the parent bird.

Behind me now are Haverigg dunes, a wind farm and a low-security prison. But tonight, having climbed Black Combe to see the bright coast from above, the views from The Wayside guest house and Whisky Barn at its foot are green and agricultural. Tranquillity radiates from the fabric of the building itself. Dan chats while Emiko cooks.

“We’re techy people” he says. “We met working on software solutions in Hong Kong. We hope the coast path will bring people here – we need safer cycling routes next. We don’t want the traffic they have got in the Lakes, people can come without cars. But this area needs something, with the farms employing fewer people. Tourism is better than being a nuclear waste dump.” Dan is unhappy that the coast is being considered as a site for a Geological Disposal Facility for radioactive waste.

“Long shingle beaches are empty but for ringed plovers, curlews and oystercatchers”

Arriving at Ravenglass via long shingle beaches, empty but for ringed plovers, curlews, oystercatchers, and the sand martins whooshing in and out of their burrows in eroding cliffs, I am feeling dreamy. The ice-cream parlour, despite the day’s warmth, is cool inside.

“It’s the old butcher’s, so the walls are thick,” Sam Bowden tells me, serving scoops of sea-buckthorn ripple. “We get our milk from Andy’s farm less than a mile away.”

At the confluence of the Esk, the Mite, and the Irt, Ravenglass is dominated by estuary, whose flux I find thrilling. An unusually high tide swills around the coast path sign. But later, at low tide, I step barefoot on to the mud, and hear it popping. The flats are pocked by wormcasts and spiked with samphire. Periwinkles graze shallow pools. There’s a splash as a herring gull scoops up a crab, tosses it about, then leaves it on the sand.

NUCLEAR COMMUNITY

My hatred of nuclear power, nuclear weapons and nuclear waste does not extend to the people who work in the industry, or live in its shadow. Aesthetically, I appreciate a gritty landscape. But Seascale feels more like a retirement village than the industrial hub I had expected. Michaelmas daisies run riot, there’s action on the bowling green, and a policeman comes out of the Co-op with a jar of pasta sauce. Gentlemen with coiffured silver hair seem pleased and surprised to see me. I ask one with a comb in his pocket if he has walked the coast path.

“Not really,” he says. “But I used to work at Sellafield so I cycled every day up the cinder track. You’ll cross some slabs I laid 25 years ago. I like to think mine are the ones which don’t wobble.” None do.

The coast path lies seaward of Sellafield, where sprawls of dune flowers are intoxicating. Passing the perimeter fence, I find the plethora of danger signs, trucks and chimneys fascinating. Four men in blue uniforms wave. The path seems to shimmer. But also there’s vetch, ragwort, sea spurge, burnet rose, bloody cranesbill, Japanese rose, kidney vetch, honeysuckle, bedstraw, columbine, and sea holly growing nearby – I lose count. Sea rocket. Scabious. Angelica.

Union Jacks, Jolly Rogers and Cumbrian flags flap above Braystones’ beach houses, but the weather is changing. The waves are bigger. The shingle sounds louder, the curlews mournful. Cloud dissolves the peaks and the Isle of Man disappears. I feel completely at home, Cymru (Wales) being not so different. As the path undulates approaching St Bees, sheep become blurs on a smudged horizon and rain washes my face.

MUD LIFE

Georgia de Jong Cleyndert, from Cumbria Wildlife Trust, wisely opts to meet me in St Bees Beach Café instead of on the path, to tell me about the Marine Conservation Zone that shares this coastal strip. We gaze through steamy windows at brown waves smashing the red sandstone cliffs. Georgia tucks her long hair behind an ear and paints a vivid picture of life beneath those cliffs – boulder communities, crabs and nudibranchs, starfish and anemones.

“There’s often a misconception about the Irish Sea – that it’s just dirty and lifeless and muddy. But mud is so important! It sustains invertebrates which get eaten by fish, that support breeding birds and porpoises.” Her enthusiasm is palpable.

“We want people to get out there exploring rockpools. As long as they put the rocks back carefully and don’t tread on the honeycomb reefs or take anything off the beach.” “Not even shells?” I say guiltily and she looks uncomfortable. “It’s about getting the balance right,” she says.

Under St Bee’s Head, guillemots and razorbills rise and fall on the swell, waiting out the tide. The wild and human coastal communities are delicate, but rich. Walkers are well catered for with trains, and accommodation and tea when it’s needed, but there is room, it seems, for more sensitive, locally driven tourism – avoiding the Lakes’ mistakes.

My journey ends in spirited Whitehaven, where at sunset I walk around the intriguing matrix of harbour walls. The fishermen are out, and a few kids, too, amid a sprawl of rods and bikes.

“We got some fish!” beams one with a cap. “A skate. A plaice. Two catsharks and a whiting, but ’ee don’t count. We put ‘em all back because we don’t want to hurt ‘em.” There’s a kind of balance in that.

Julie Brominicks is a landscape writer and author who lives in Cymru (Wales). She specialises in wild places, local exploration and sustainable travel. Her book The Edge of Cymru: A Journey is published by Seren.

CUMBRIA’S NEW COAST PATHS

Cumbria’s coast path will eventually form part of the England Coast Path, which, when complete, will be a National Trail 2,700 miles (4,345 km) long. nationaltrail.co.uk

Which Cumbria sections are open?

The stretch between Allonby and Whitehaven, completed in 2014, was joined in 2020 by the section circumnavigating Walney Island. Julie walked the most recently created parts – the 2022 Green Road Station to Silecroft section, linking to the 2021 Silecroft to Whitehaven section, totalling 43.2 miles (69.5 km). Although complete, gaps remain over the River Esk and the River Irt, which walkers are advised to circumnavigate using existing trails (or trains), until hoped-for bridges can be financed.

What remains to be done?

Works on the remaining sections between Allonby and Gretna in the north, and Green Road and Silverdale in the south, are in progress with an aim for completion by the end of the current parliament in 2024.

NOW GO TO THE CUMBRIAN COAST

Where to stay, eat and explore on the Cumbrian coast, by Julie Brominicks

STAY

Wayside and Whisky, Whitbeck

This sublimely peaceful B&B in a gorgeously restored barn has views of Black Combe. Emiko’s superb hospitality includes excellent cooking; even the baked beans are homemade. 01229 718 883, thewayside.uk

Harbour Lights, Haverigg

Between holiday parks, this convivial campsite (with pods) is also home to Paige’s Riva Gelato ice cream, made on site. Ideally placed for Hodbarrow RSPB Reserve. 01229 777 300, harbourlightscampsite.co.uk

Seacote, St Bees

Hotel and campsite accommoation. The static caravans (above) are perfectly placed for the coast path.

01946 822 777, seacote.com

Self-catering accommodation in a great location – guests have access to roam the gardens by evening, or stroll by the river. 01229 717 614, muncaster.co.uk/coachmansquarters

Cumbrian Lodge, Seascale

A friendly B&B with great home cooking by Paul and Angela – book in advance if you’d like an evening meal. 01946 727 309, cumbrian-lodge.co.uk

EAT

Estuary View Gallery and Tearoom, Ravenglass

Conjuring up fresh cakes, peppery soups and delectable cheese scones, this coast-facing café is set under Rosegarth guesthouse. 01229 717 754, estuaryviewstearoom.co.uk

Tarn Bay Treats

The tiny hut – furnished with coffee machine, ice-cream freezer and homemade cakes (don’t miss Aunty Jen’s knitted hats) – was a community lockdown project that is now irresistible to walkers. Pay by honesty box. facebook.com/tarnbaytreats

RAINY DAYS OUT

Muncaster Castle

Lively, with gardens, woodlands, falconry displays and a well-conceived eco-discovery centre. Even the castle is animated by archivists and upholsterers at work. 01229 717 614, muncaster.co.uk

Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway

This polished narrow-gauge steam train once carried quarried stone, belying its tougher industrial past. Enjoy seven miles of stunning scenery, a café and museum. 01229 717 171, ravenglass-railway.co.uk

HERITAGE

Millom Heritage and Arts Centre

Themed rooms, from prehistory to poetry, contain expertly interpreted local exhibits such as ‘witch bottles’ and a medieval hand-sanitiser. Free entry, locally loved, this museum has bags of soul. 01229 772 555, millomhac.co.uk

The Beacon, Whitehaven

For a larger, techier experience of local history, artefacts here are mixed with cyber displays; I watched a boy teach his grandad how to build a digital schooner. 01946 592 302, thebeacon-whitehaven.co.uk

DRINK

The Ratty Arms, Ravenglass

This down-to-earth railway pub on the Ravenglass platform of the Cumbrian Coast Line has avoided gentrification. Enjoy a great pint of Loweswater Gold. 01229 717 676, ravenglass-railway.co.uk/the-ratty-arms

The Manor, St Bees

With real ales and cheerful service, The Manor is accustomed to catering for thirsty walkers, located as it is at one end of Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Path. 01947 820 587, themanor-stbees.co.uk

THREE SHORT WALKS

Millom Circular (5 miles)

Boasting estuary views, orchids and terns, this walk is accessible for robust wheelchairs. Take the coast path from Millom, pass Haverigg lighthouse and turn right through Port Haverigg holiday village, returning to the path along the lagoon wall.

Black Combe (8.8 miles)

At 600m, it’s almost a mountain – visibility can be poor and the drop treacherous. From Whicham (near Silecroft station) climb to the trig point for epic views of the coast, then bear northwest before descending. Return to Whicham via Whitbeck.

St Bees to Whitehaven (6.5 miles)

Walk from St Bees Head via Fleswick Bay’s sea caves and auk colonies nesting on sandstone cliffs. Wildflowers around the disused colliery welcome you to Whitehaven and its large, historic harbour. Return via the Cumbrian Coast Line.