OPINION

Nicola Chester

A rural childhood spent in nature is a privileged one, but there are hardships, too.

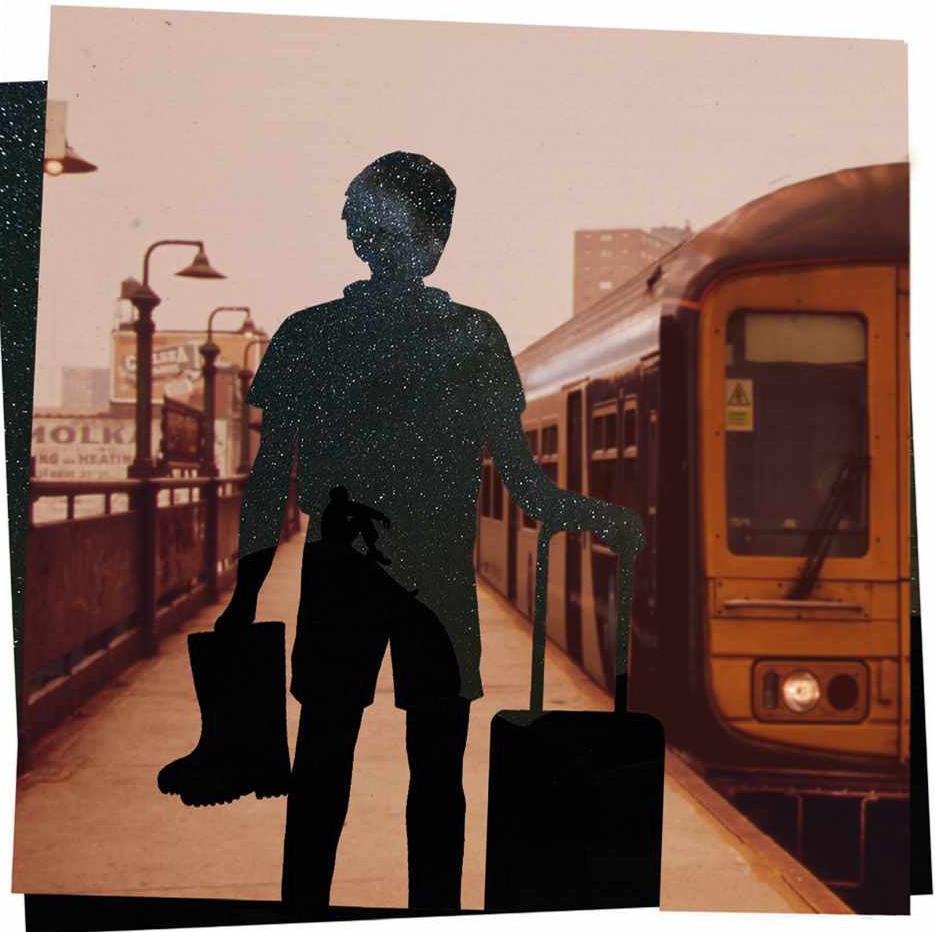

“High summer, and the days stretch out even longer for the young people finishing formal education. Many rural teenagers will be at the point of fledging the village that raised them, with mixed feelings.

Some will be cueing up jobs or apprenticeships away, desperate to pass driving tests, while others will be off to university. Most will be keen for excitement: somewhere to go. But also perhaps, among apprehension, they will experience those first stirrings of appreciation and nostalgia for a very different upbringing than that of the friends and acquaintances they will meet.

Our three children have had a deeply rural upbringing. Now that two of them are at university, they realise quite how different that upbringing has been compared to their peers’ experience. There are marked privileges, yes, but quirks and disadvantages, too. There are long bus rides that make after-school clubs impossible, and mud is a constant. It is normal to know how to round up loose animals, to sit with an ill neighbour for ages until help arrives; to be able to chop wood and light a fire as the only source of heat sometimes. It is normal not to understand the tinkling of an ice-cream van, or be unable to sleep where there are street lights and traffic.

Young people are often unfairly demonised in the countryside, where loud antics and self-expression stand out and a skateboard has no place. An old shelter in the playground was taken away because “it encouraged youths to gather” although that was its purpose.

EXPERIENCING THE WORLD

But what is there to do when you have outgrown the playground? Friends are scattered far and wide and everything has to be planned around lifts or the long wait for the bus. Spontaneity is impossible. Even when they are old enough to go to the one pub left, parents and neighbours are also there, cramping their style. Part-time jobs are few, yet offer stories others won’t have: fancy events at The Big House, horses, shovelling for the grain dryer, harvest help, egg-picking.

Walking and cycling are important transport, but rural buses and trains mean the cinema! Cafés! Shops! Places to study that aren’t your bedroom; nights out; pubs that your parents aren’t in; friends.

Normal, for everyone else. And it’s natural, necessary and healthy to want to leave a rural community for experience of the wider world. Not all have the opportunity or desire to do so, of course, while others find they can never come back, even when they want to. This leaves a big age gap.

So how do we involve and learn from young people when they’re here? Scouts and Young Farmers feature strongly in many local lives, but the ‘young people’ on the Parish Council, village fête or village hall committee are all distinctly late-middle aged.

I seek my children’s perspectives. Yes, country life can be isolating; but they loved the privilege of time outside. They can take or leave social media (poor signal), are quick to offer help, resourceful, happy in their own company and resilient if a plan doesn’t come off. They have far fewer cultural references than others and, hilariously, all three are united by friends that ask them often “did you live under a rock?” Yes. A big, grass-covered, chalky one.

In a place where everybody knows your business, they have wonderful memories: of epic walks and river swims; cider with friends in field corners; meteors and golden rides, bareback on borrowed horses. Rural rites of passage that, over time, negate all the hardships.”

Nicola Chester is the author of Richard Jefferies Award-winning and Wainwright Prize Highly Commended book On Gallows Down.

Have your say

What do you think about the issues raised here? Write to us or email editor@countryfile.com