Our seaside blooms

Wherever you are on the coast this summer, you’ll be in the company of stunning wildflowers. Phil Gates offers brilliant insight into the species – and the varied seaside habitats – that you will encounter

Buffeted by desiccating winds, doused in salt spray, buried by shifting shingle and blasted by abrasive sand: our seaside wildflowers are a tough bunch. You have to admire their sheer tenacity, surviving on the edges of our islands in habitats that are as close to being truly wild as it is possible to find in Britain.

They include some of the bestloved species in the flora of our maritime nation. Part of their attraction must lie in the nostalgic association between plant and place, recalling summer-holiday trips to sparkling coasts fringed with vibrant flowers.

Look closely at seaside wild plants and it becomes apparent that many share characteristics that allow them to survive in such extreme, unstable environments. Some have adaptations for absorbing and conserving fresh water, such as unusually deep roots and thick, fleshy leaves that retain moisture. Often, a thick, waxy leaf cuticle minimises water loss and gives foliage an attractive blue-grey, glaucous sheen.

Botanists categorise the extreme coastal specialists as halophytes – species that evolved to cope with salt concentrations that kill most plants. Sea lavender excretes salt from glands to the leaf surface, where it crystalises until washed away by rain. Marsh samphire safely locks away saline solution in compartments within its succulent leaves.

Like other wildflower habitats, the coast faces threats from human activity. The landward margins of sand dunes are often developed as leisure facilities. Where river estuaries discharge into the sea, nutrient enrichment and silt deposition from agricultural runoff and sewage can be harmful to plants adapted to a low-nutrient lifestyle. But the prime threat to our seaside flora is coastal erosion, which will increase as climate change triggers further sea level rise.

Storm surges, thundering waves and fierce currents can eat away long stretches of dunes, reshaping the coastal landscape. In many places, cliff-edge flora, confined to a thin zone between agricultural land and the sea, teeters on a precipice, when soft sandstone and limestone are undercut by waves. Salvation for salt marshes, trapped between rising sea levels and sea defences that protect low-lying agricultural land, might come from deliberate sea-wall breaches and a managed retreat, allowing new salt marsh to form as the sea creeps inland. Nowhere in the UK is more than 70 miles from the nearest coastline. Millions of us will travel to the seaside this summer: take a wildflower guide and a picnic to enjoy perfect coastal botanising.

Dunes

Dune systems, sculpted from wind-blown sand and some of the finest natural features of our coastline, provide complex, varied habitats for some of the most colourful seaside wild flowers. In the vanguard, on the beach strandline, pioneering sea rocket is rooted only a few feet above the high-tide line. Behind towering cliffs of sand, precariously stabilised by creeping roots of marram grass, lie sheltered dune slacks, carpeted with bird’s-foot trefoil, wild thyme and orchids, teeming with bees, grasshoppers and butterflies. Further inland, where the influence of the sea diminishes, you’ll find a tangle of wind-pruned pricky shrubs and wild roses.

SPECIES

1 Sea rocket Cakile maritima

A strand-line specialist, sea rocket flowers among flotsam and jetsam cast up by the highest tides. Buoyant seed pods swell after the lilac flowers are pollinated, acting as lifeboats for seeds that are dispersed by coastal currents, until they are washed up on distant shores by breaking waves. An ocean traveller.

2 Sea holly Eryngium maritimum

This handsome and unusual member of the carrot family has stiff, spiky leaves, mottled pale blue, green and gunmetal grey. A thick, waxy cuticle protects the foliage from constant abrasion by windblown sand. Globular inflorescences of tiny bright blue flowers sit above a whorl of spiny bracts. Deep roots, up to eight feet long.

3 Sea bindweed Calystegia soldanella

Rarely twining and climbing like other bindweeds, these prostrate plants have shiny succulent leaves and stems that creep across dunes. They sometimes become partially buried in shifting sand before resurfacing. Its large, pink, cone-shaped flowers have five narrow white stripes, bringing to mind seaside shop awnings and strawberry and vanilla ice cream.

4 Burnet rose Rosa spinosissima

The most intensely fragrant native rose, with creamywhite flowers, burnet rose is usually the first native wild rose to bloom, in old dunes and clifftops. It is also the most painfully prickly; take care not to sit or kneel on any prostrate stems when picnicking. It produces shiny purple rosehips that become black as they mature.

5 Sea buckthorn Hippophae rhamnoides

This spiny shrub forms impenetrable thickets behind old dunes. It is often planted to stabilise sand, and offers an invaluable refuge for coastal birds. The grey-green leaves are covered in silvery scales that reduce water loss, an adaptation to life in a windy environment. Tiny green flowers are followed by orange berries, a food source for migratory birds.

Grassland

A wildflower-fringed coastal walk along sea cliffs, with a view to the horizon, the sound of waves below and skylarks overhead, is a treat for the senses. Plants that live in the ribbon of grassland that is too precarious to cultivate offer a hint of a flora that existed before agriculture’s impact. Wind has the greatest influence here, pruning low trees and shrubs into contorted forms. This tough coastal scrub of coconut-scented gorse, hawthorn and blackthorn provides fruits and seeds for birds in autumn.

SPECIES

6 Sea pink Armeria maritima

Pink pom-poms rise above dark-green cushions of narrow leaves from late spring, with the finest displays in early summer. Also known as thrift, sea pink often still flowers in September, followed by papery seed heads.

7 Wild cabbage Brassica oleracea

This crinkly-leaved ancestor of cultivated cabbages, cauliflowers and Brussels sprouts grows in crevices in sea cliffs, producing strikingly tall yellow inflorescences. It is debatable whether some populations are truly wild or just escapees from ancient gardens.

8 Scurvy grass Cochlearia officinalis

These clusters of white, four-petalled flowers are a common sight on seabird cliffs. A member of the cabbage family, the plant’s neat rosettes of shiny succulent leaves have anti-scorbutic properties, mentioned in Captain Cook’s diaries as a defence against scurvy.

9 Navelwort Umbilicus rupestris

This is unmistakable, even before the tall spikes of greenish-yellow flowers appear. Its round leaves have a distinctive dimpled ‘belly button’ in their centre, where they join the leaf stalk. Mostly confined to southern and western coasts, it can often be found growing in seaside drystone walls – hence its other name, wall pennywort.

10 Bloody cranesbill

Geranium sanguineum Often the first large-flowered cranesbill species to flower, these bright magenta blooms enliven cliff-edge grasslands. The county flower of Northumberland grows abundantly along that coast. The long-beaked fruits have a catapult mechanism for hurling seeds into surrounding vegetation.

11 Rock samphire Crithmum maritimum

This carrot family member is mostly confined to the steep sea-cliff faces, so is best viewed with binoculars from a safe distance. Its crushed leaves emit a whiff of sulphur. It was once pickled in vinegar and spices, after being harvested at great risk: “Half way down/Hangs one who gathers samphire, dreadful trade!” (King Lear).

Marshland

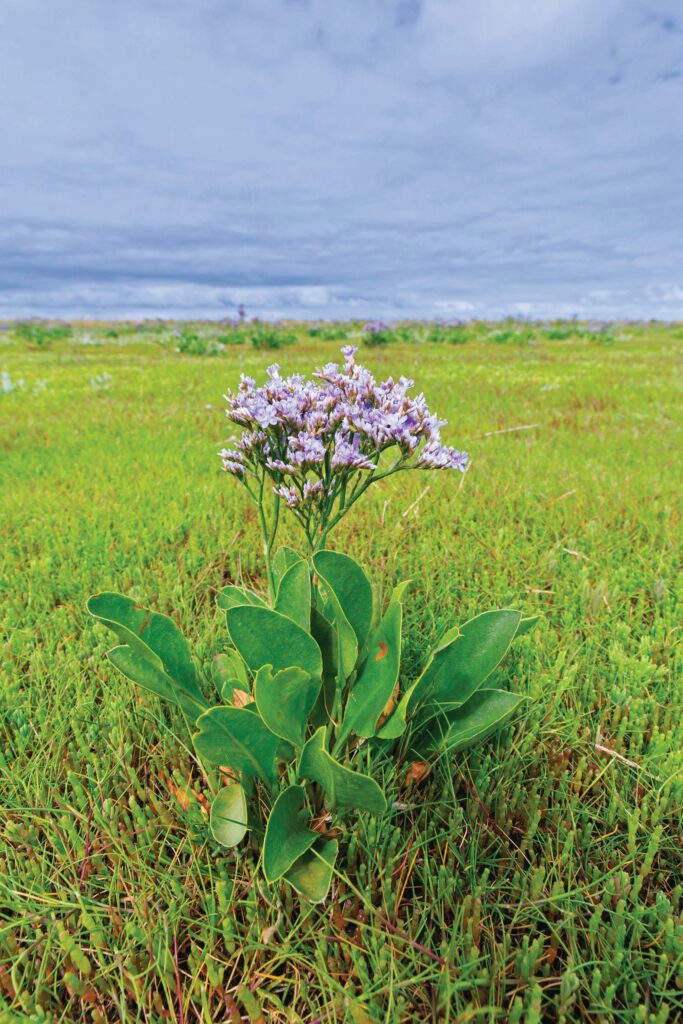

At low tide, as the sea drains away, leaving mud banks where sea lavender and sea aster bloom, there is melancholy beauty to be found in a salt marsh. Redshanks feeding in muddy creeks make their desolate calls. When the tide creeps back, plants in the lower zone sit in saline solution, rooted in anaerobic mud; then, when it recedes, they are left baking in a summer heat haze or exposed to freezing winds in winter. In the upper zone of the marsh, where fresh water runs off the land, the water is brackish, so plants that live there must cope with major fluctuations in salinity.

SPECIES

12 Marsh mallow Althaea officinalis

Stroke the grey-green leaves: they are downy and beautifully soft, perfectly complementing the large, delicate rose-pink flowers that sit in the leaf axils. Mucilaginous, gelatinous sap from the roots was formerly harvested to make the well-known sweet-treat, marshmallow. Sadly, the plant is now an uncommon sight in the upper, brackish banks of saltmarshes.

13 Sea lavender Limonium vulgare

Sea lavender produces one of the finest saltmarsh floral spectacles when, in high summer, a shimmering haze of small blue-grey flowers extends across the mud banks, on stems just tall enough to keep their heads above the waves on an incoming spring tide. The dried ‘everlasting’ papery flowers retain their colour until early autumn.

14 Sea aster Aster tripolium

Often abundant, sea aster grows right across saltmarshes, from the upper brackish reaches to the edges of mud banks near the sea. Pretty mauverayed, yellow-centred flowers are similar to the closely related garden Michaelmas daisy of North American origin, and are highly attractive to bees and butterflies in late summer.

15 Marsh samphire Salicornia europaea

This distinctive mud-dweller has branched, jointed succulent stems, often colonising large areas of bare mud. Once subsistence food for coastal communities, it is now harvested and sold as a fashionable vegetable. It is also known as glasswort, because its ash contains high levels of sodium and was formerly used in glass-making.

Shingle

Deep roots and salt spray-resistant foliage are keys to survival in this barren landscape of pebbles, where fresh water drains away quickly and waves, crashing on the shore, fill the air with salty mist. The beauty of the plants that thrive here is enhanced by stony surroundings that create a natural rock garden, in what might otherwise be a desolate shoreline. Flowers that grow in shingle can only gain a secure foothold on the stable upper edge of the beach, but often spread with branching underground stems that thread their way between the stones, forming large colourful patches.

SPECIES

16 Sea kale Crambe maritima

Always impressive, even when seen from a distance, sea kale has magnificent, thick, glaucous blue-green foliage and dense sprays of large white flowers. Anchored by roots that penetrate deep into bare shingle banks, its shoots were once blanched then harvested as a vegetable. It is now an uncommon plant, due to overexploitation – but once seen, never forgotten.

17 Sea pea Lathyrus japonicus

Now uncommon, sea pea is mostly confined to southern and eastern coasts. Its stems creep over shingle, producing short racemes of magenta flowers that fade blue with age. The seeds are large – and legend has it that the plant was once sufficiently abundant for Suffolk coastal folk to use the seeds to survive a 17th-century famine.

18 Sea campion Silene uniflora

A prolific bloomer on shingle banks, this forms dense, low-growing mounds, with stems that quickly produce new shoots when partially buried. Its mounds of solitary white flowers have deeply cleft petals. The toothed seed capsules easily break away on windy days when ripe, to be tumbled along the beach, scattering seeds as they go.

19 Yellow horned-poppy Glaucium flavum

Golden-yellow flowers, up to three inches in diameter, on tall stems rising from rosettes of silvery-grey, crinkly, waxy leaves that exude orange latex, with an unpleasant smell when damaged. Flowers that can be plentiful but short-lived are followed by extremely long, thin, curved seedpods.

Phil Gates is a naturalist who lives in County Durham. He taught biology at the University of Durham for many years, and contributes to The Guardian’s Country Diary column.