OPINION

Nicola Chester

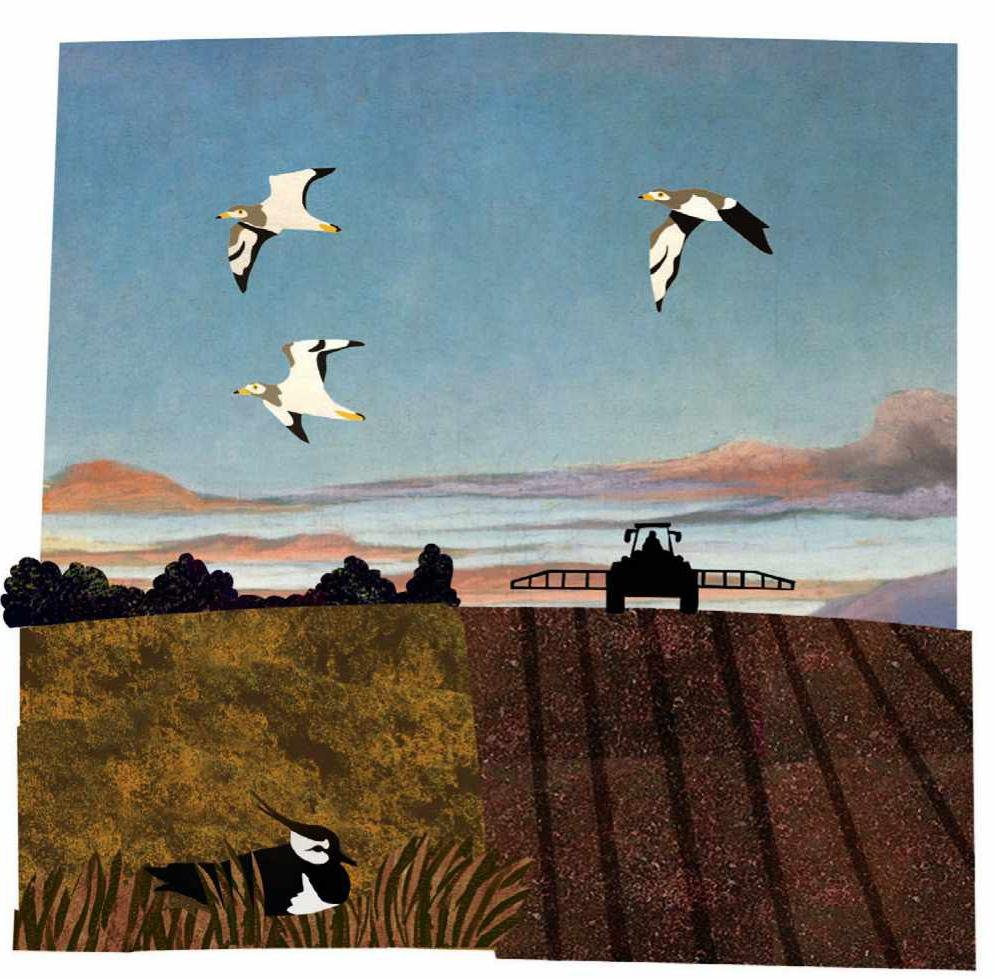

The rescue of two farmland birds brings hope among stories of loss

‘‘With the devastating news earlier this year that farmland birds have declined the most steeply, out of all the birds of Europe we are losing, it is easy to feel powerless. Our dependence on pesticides and fertilisers (combined with other factors in intensive agriculture) is undeniably the biggest cause. Living in the midst of it, the klaxon is blaring, as the fields and hedgerows fall silent.

One late-summer downland evening, there is an eerie, mournful wail: a stone curlew! And for me, proof that trying to save individual last birds – while we lobby for support for our farmers to protect and create habitat – is never futile.

This spring on the downs, I had gone to find nesting lapwings – that quintessential farmland bird, with its looping, bubbling song that is like nothing else on Earth. But, as one environmental scheme ended and another began, one of two rough-ploughed sanctuaries that had been left for them and the stone curlews had been cultivated. The lapwings were all gone. Despondent, I continued scanning the high flint fields when something moved among browsing hares: a white plimsoll line of feathered bunting, a wild goggle-eye, a bright yellow bill. A stone curlew. Two stone curlews! They had taken up residence in the arable, where they were vulnerable to farm work.

I watched awhile, then headed back to my car, buoyant with excitement, when I heard machinery behind me. My knees went to jelly. I pulled out my phone to alert the farm, but the battery was dead. I leapt up and down from the headland at the big tractor with its wide spraying arms, wildly waving mine. But the driver didn’t see me. So I ran. I ran for my car, uphill, over flints like dinosaur bones and broken crockery, slicing the soles of my wellies, to plug in my phone. With just a whisper of a signal, I messaged and pressed send.

Just when I thought all was lost, the tractor loomed into view. I flagged it down like Jenny Agutter in The Railway Children, the blood roaring in my ears. I spilled out my charm offensive in a mix of desperation, emotion and breathless laughter. The farmer was kind. Excited about the stone curlews too. He would enter the What3Words co-ordinates into the tractor’s computer, and populate it across the whole fleet to avoid the birds. I was

RESCUE NUMBER TWO

Back home, the rollercoaster wasn’t over. A familiar “peewit” stopped me in my tracks. A lapwing, in the village where they have been gone six years! The wet spring had delayed drilling and the rough ploughed field next door suggested a substitute for the habitat lost on the down. I glimpsed flight that mirrored my flung-high feelings. A spin of spread wings, wider at the tip like garden-fork tines: a wobble, a swoop, the wuthering wheeze of wings. My heart flipped. For this can only be a ghost visit from birds already gone from here. The lapwings’ needs, once perfectly evolved to our farming habits, are now destroyed by them. And yet…

Buoyed by my success with the stone curlew, I Facebooked this farmer (galvanising others). He didn’t know about lapwings, but wanted to help. He delayed ploughing and let me mark the nest until a clutch of four chicks hatched, up and running like foals: flint-and-chalk pom-poms.

I stand under the thinnest rind of a new moon. On the horizon, the last lapwings on the down are poised. There is a paddle-wing turn in the blue. A bubble of hope rises with them from my chest. I dream of them like an anxious mother, my heart, a lapwing.’’

Nicola Chester is the author of Richard Jefferies Award-winning and Wainwright Prize Highly Commended book On Gallows Down.

Have your say

What do you think about the issues raised here? Email editor@countryfile.com