OPINION

Nicola Chester

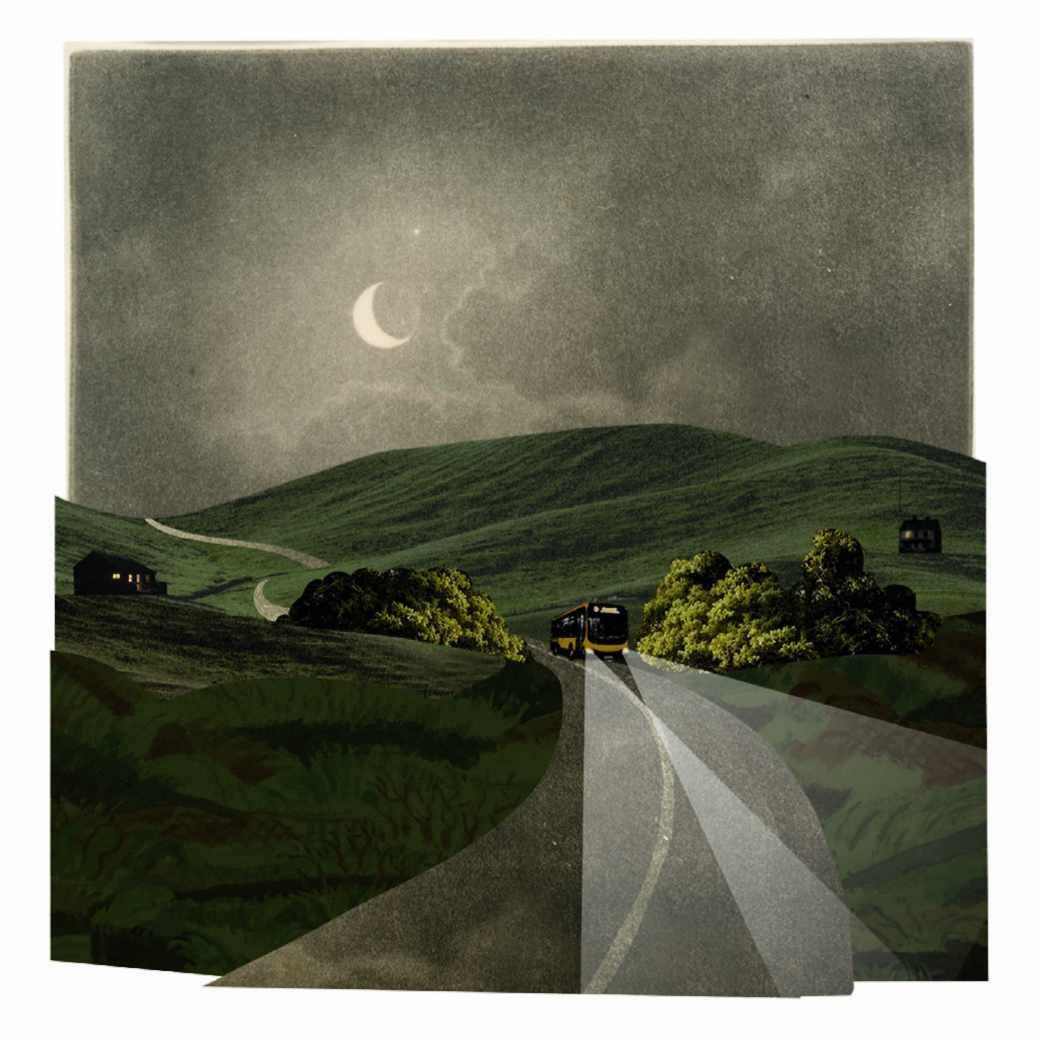

Rural buses mean independence for young and old – but they’re a dying breed

“Eleven at night and the lane is dark and quiet. There is just enough light in the sky to differentiate the outlines of trees, and my eyesight has adjusted enough to make out the paler, dusty, straw-lined edge of the road. I have my phone torch switched on, but only in case of cars.

Right on cue, a little light bobs round the corner of “the bad bend” in the road, a quarter of a mile down, and I waggle my phone light so my daughter knows not to take the short cut over the fields (she has been babysitting and is more than capable of walking home alone, but I like the walk). The walking rhythm of the light is so familiar it makes me smile. That long, loping, ‘country’ stride that covers distance effortlessly, over any terrain or incline: field, plough, long stretch of potholed lane, assuredly, even in the dark.

For rural teenagers, walking is a necessary form of transport – and a bike, even more so. For several years, my rusty old mountain bike meant my other daughter could sustain three separate jobs looking after animals at weekends. But apart from that, until you’re old enough or able to drive, independence is limited to a couple of buses a day, and only if you’re lucky to have those.

At the start of this school year, there are new faces, crisply uniformed, at the bus stop – some having walked a good way to get there, or been dropped off. It’s the start of a new journey in resourcefulness and patience, too. A learnt resilience, and the ability to read and join up bus timetables, and not be late.

But rural areas are becoming ‘transport deserts’, in thrall to the car in a vicious cycle. It’s almost impossible to live well in the countryside without a car; a recent application for new-build affordable housing was turned down because there was “no transport infrastructure for those on low incomes”.

A COMMUNITY SERVICE

For teenagers, buses are a lifeline – to friends, town, jobs, educational and cultural experiences. Many young people don’t want to learn to drive because of the expense and their environmental footprint, but it seems that is often their only option. The last bus home from town is at teatime.

But of course, this also affects others who don’t drive, particularly older people. Without a decent, cheap and connecting public transport system, so much is out of reach. Dentist and GP appointments, clinics, the cinema, meals out with friends, gym classes, a public swimming pool, talks and gatherings. These things can’t be bought online and delivered. Without access, people are cut off and disadvantaged; missing out on the chance to connect and socialise, a sense of loneliness, helplessness and isolation blooming instead. But it wasn’t always this way. It doesn’t have to be.

Mum gave up driving three years ago, but is active, revels in her independence and relies on the bus. She is the first to extoll its community values. “All life is here!” She says. “We chat, all ages. We help each other out.”

My son spent two years studying music at a Higher Education College in a town 12 miles away on a small bus, nicknamed ‘the bread van’. He shared his rides, guitar in hand, with a regular group of retirees. They asked him for tunes, shared their sweets and woke him up before his stop. In return he laughed at their jokes, helped those who needed it on and off and explained what ‘woke’, ‘scams’ and ‘pronouns’ meant.

A bus can draw a community together and strengthen it, even as it takes people to the wider world and helps spread wings. It also brings them home again.”

Nicola Chester is the author of Richard Jefferies Award-winning and Wainwright Prize Highly Commended book On Gallows Down.

Have your say

What do you think about the issues raised here? Email editor@countryfile.com