HISTORY

Out of the blue

The first to publish a book illustrated with photographs, 19th-century botanist and artist Anna Atkins and her work with cyanotypes began a new era in scientific documentation, writes Rosanna Morris

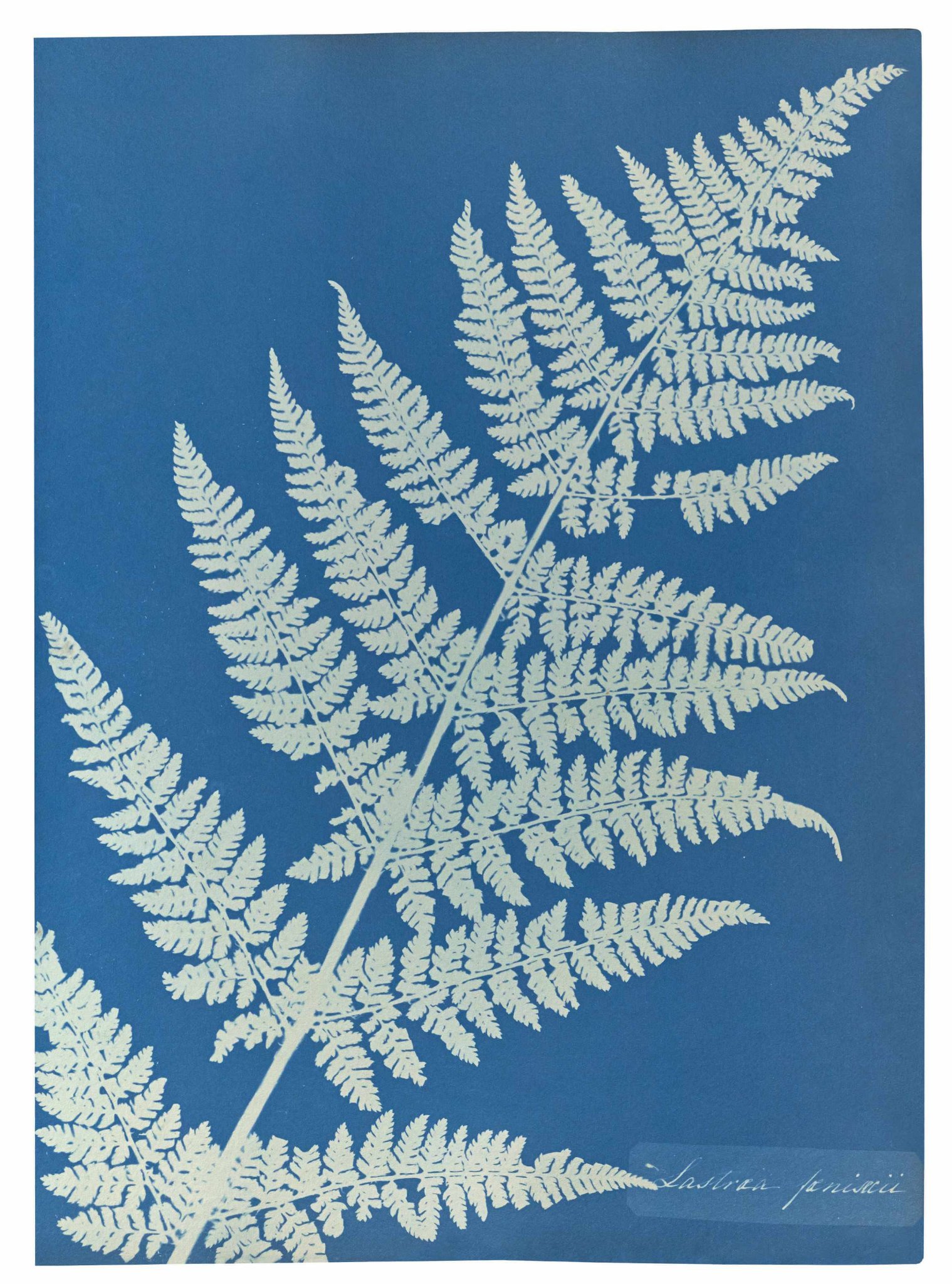

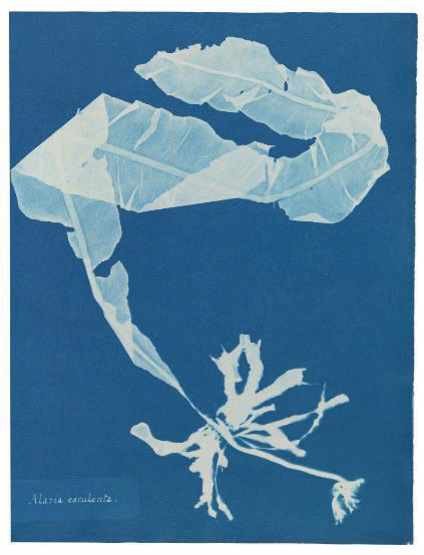

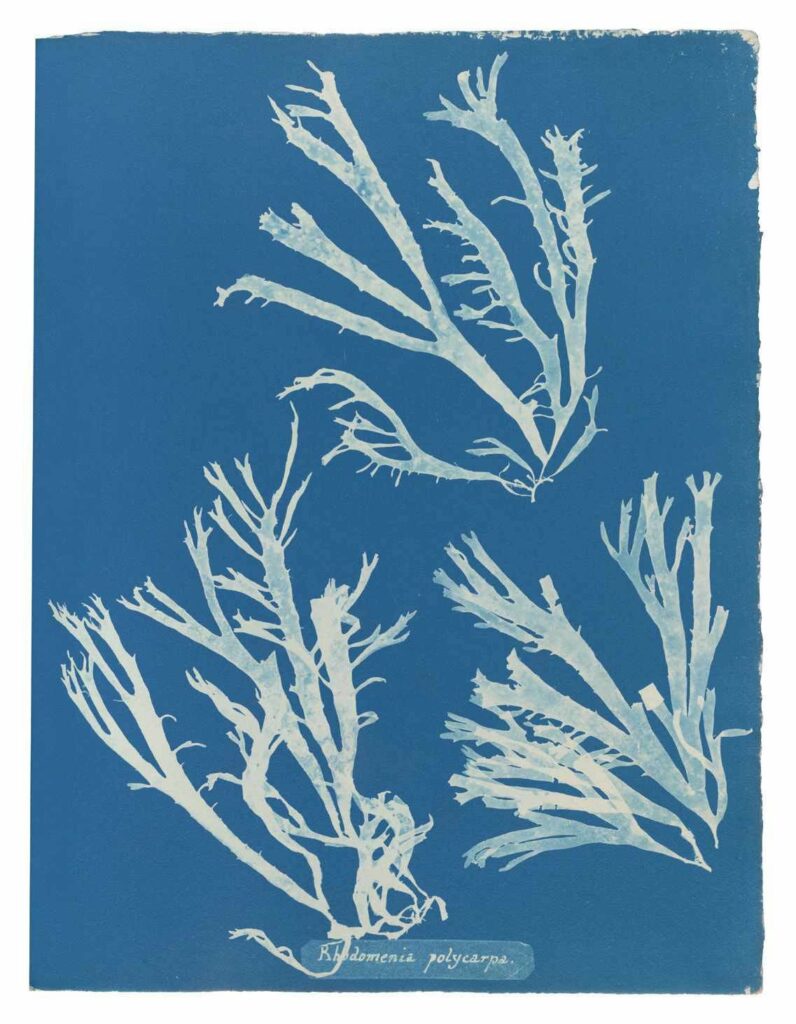

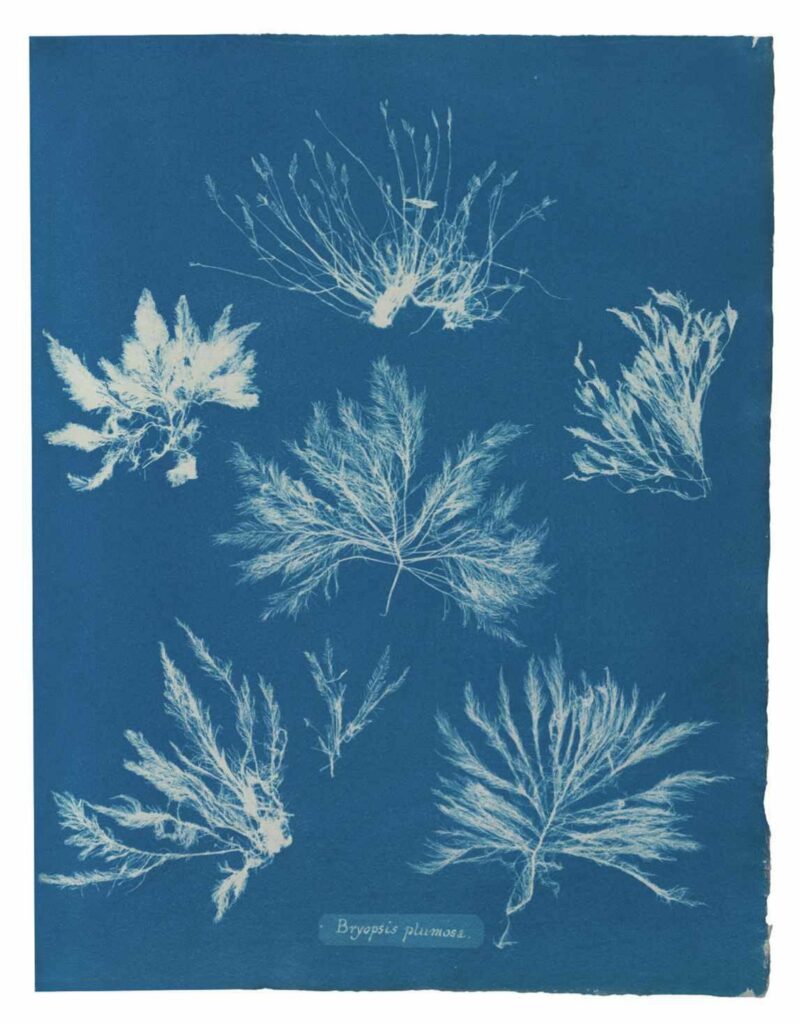

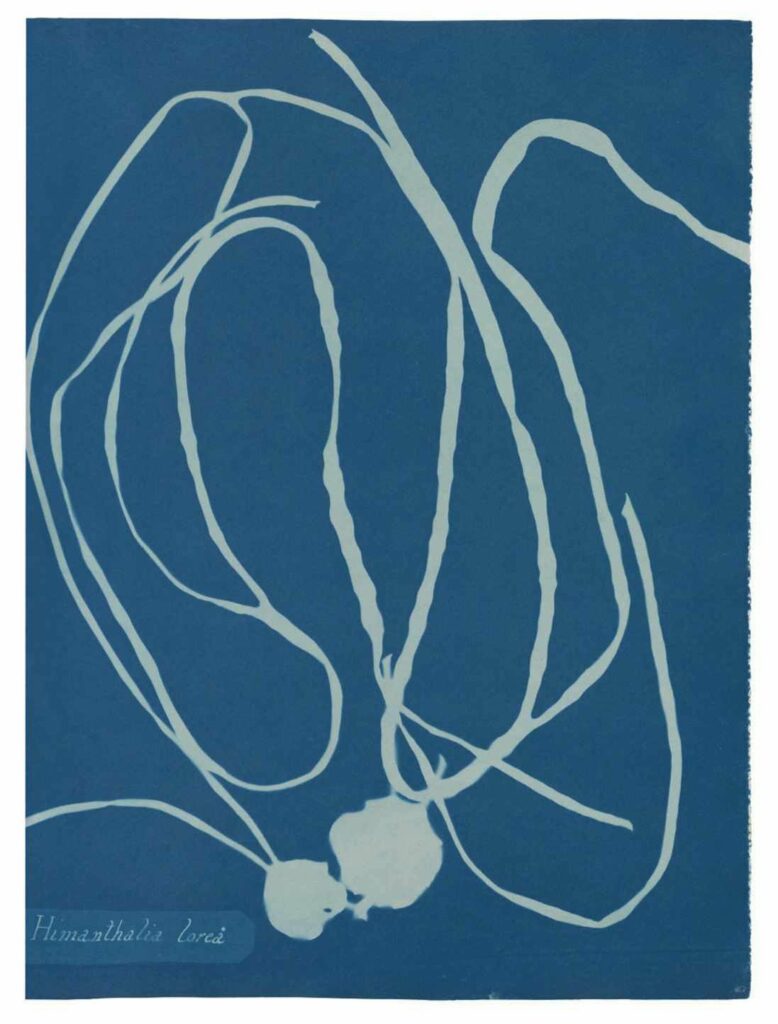

During the pioneer age of photography, when Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot were unveiling their inventions, a woman named Anna Atkins published 15 copies of a book entitled Photographs of British Algae. The albums had striking Prussian blue covers and inside contained page after page of beguiling, ghostly white silhouettes of algae and seaweed captured against the same rich blue pigment.

It was 1843 and a book of this kind had never been produced before. Not only was it the first photographically illustrated book, but it was also the first publication to explore the technical and artistic possibilities of the cyanotype, invented by chemist Sir John Herschel a year earlier. It brought together photography and botany – two major subjects of the Victorian age – and the results were scientifically accurate and intensely beautiful.

In the foreword of her unsigned book, Anna penned: “The difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects so minute as many of the algae has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves, which I have much pleasure in offering to my botanical friends.”

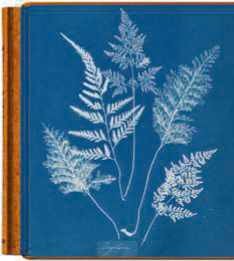

This seemingly high-tech cyanotype involved a simple photochemical process. Salt loaded with iron was spread on to paper, an object arranged on the paper, then exposed to sunlight, which caused a chemical reaction. A negative outline of the object would then become visible when the paper was submerged in water and the paper oxidised. The method was easy to master, and is still a popular artistic medium today. But in the days before cameras, creating these photograms must have felt like magic. And what Anna produced in the succeeding 10 years was extraordinary: several volumes and thousands of impressions of plants using this technique.

SCIENTIFIC UPBRINGING

Anna was born in Tonbridge, Kent, in 1798 and lost her mother when she was a few months old. She was brought up by her father George John Children, the son of a landowner and banker. John was interested in mineralogy and chemistry and was deeply immersed in the scientific community. His profession had a profound influence on Anna. A fellow and later secretary of the Royal Society, he allowed Anna to sit in on society meetings where the latest scientific findings were discussed. Their home was an inspiring place of experimentation, and John gave Anna lessons on the basics of chemistry. John went on to work for the British Museum. In 1825, Anna married John Pelly Atkins, a prosperous merchant and a friend of her father’s. They lived between the country house Halstead Place in Kent and London. Her husband encouraged her love of science and their comfortable income allowed her to broaden her interests in botany.

Anna was particularly interested in British algae and, like many affluent Victorians, she loved collecting and classifying species. This obsession with botany coincided with revolutionary advances in photography that occurred almost simultaneously. The beginning of January 1839 saw Louis Daguerre showcase his Daguerreotype in Paris, then weeks later, William Henry Fox Talbot, a friend of Anna and her father, presented his paper on developing his own photographic process to the Royal Society. Early adopters, Anna and her father ordered a calotype camera, but the calotype process was complicated. When a book on British algae was published in 1841 without visuals, a frustrated Anna set about creating her own, and when Sir John Herschel, another family friend, invented the cyanotype in 1842 and sent a letter to Anna’s father explaining it, she jumped at the chance to experiment.

Anna collected specimens from the ponds around Kent and the coast, then pressed and dried them at Halstead Place. To create a cyanotype, she would place a plant on to the paper prepared with iron salts and set it into a frame, holding the plant against the paper with glass. In her garden, she would install prepared frames on wooden shelves and expose them to the sun long enough for the sunlight to trace the plant outlines on to the paper. Anna worked in her outdoor laboratory for 10 years, also capturing flowers, feathers, lace and ferns, creating around 10,000 images – the most extensive, consistent application of the cyanotype process.

During this time, she produced two major works – Photographs of British Algae (1843–1853) and Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns (1853), the latter produced in collaboration with her friend Anne Dixon. They were not commercially distributed, and Anna didn’t sign the books, instead giving them to museums and her friends.

OUT OF THE SHADOWS

During her lifetime, there were no exhibitions or public demonstrations of cyanotypes and after she died in 1871 at the age of 72, Anna’s achievements were almost lost to history. Halstead Place fell into ruin during the Second World War and was demolished in 1952.

“After she died in 1871 at the age of 72, Anna’s achievements were almost lost to history”

Thankfully, Anna was eventually recognised due to the work of Larry Schaaf, the American photographic historian and director of the William Henry Fox Talbot Catalogue Raisonné at the University of Oxford. Schaaf discovered her work in the 1970s while a professor at the University of Texas. He was intrigued by two unsigned 19th-century photographic prints he found in the Gernsheim Collection of photography and the archive of Sir John Herschel. He eventually tracked down copies of the algae book. Through his research he proved that Anna was behind the first photographically illustrated book; she had issued her first volume eight months before William Henry Fox Talbot released the first part of his book The Pencil of Nature.

In recent years, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the New York Public Library have held landmark exhibitions on her. And this year, a new book on her seminal works has been published, bringing together Photographs of British Algae and Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns in their entirety.

Anna did not seek recognition for her contributions, but she did prove that documenting plants photographically could be both scientifically important and artistically pleasing.

Anna Atkins. Cyanotypes by Peter Walther is published by Taschen, £100.

Rosanna Morris writes about art, design and craft. She lives in Somerset and can usually be found scribbling or walking her English pointer Elma.

MAKE YOUR OWN CYANOTYPE

YOU WILL NEED

• Pre-coated cyanotype paper (available from cyanotype.co.uk)

• Clear tape

• Plants, such as leaves and flowers

• A sunny day

1 Collect a selection of leaves and flowers. Ask for permission to take plants if they’re not from your garden and ensure you stick to the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland’s code of conduct with regards to wildflowers. bsbi.org

2 Arrange your plants on the paper how you would like to capture them and consider the outline they will make. Flatten the plants against the paper to ensure the images are sharp.

3 Secure the plants to the paper using thin strips of tape.

4 Tape your paper on to a window with the plants facing outwards, or lay your paper outside with the plants facing up.

5 Expose the paper to sunlight for 3 to 30 minutes, depending on how bright the light is.

6 When ready, remove the tape and plants and dip the paper in cool water. Leave to air dry and over a few hours the print will oxidise to its final colour.