PHOTOGRAPHY SPECIAL: MACRO

The art of photographing flowers

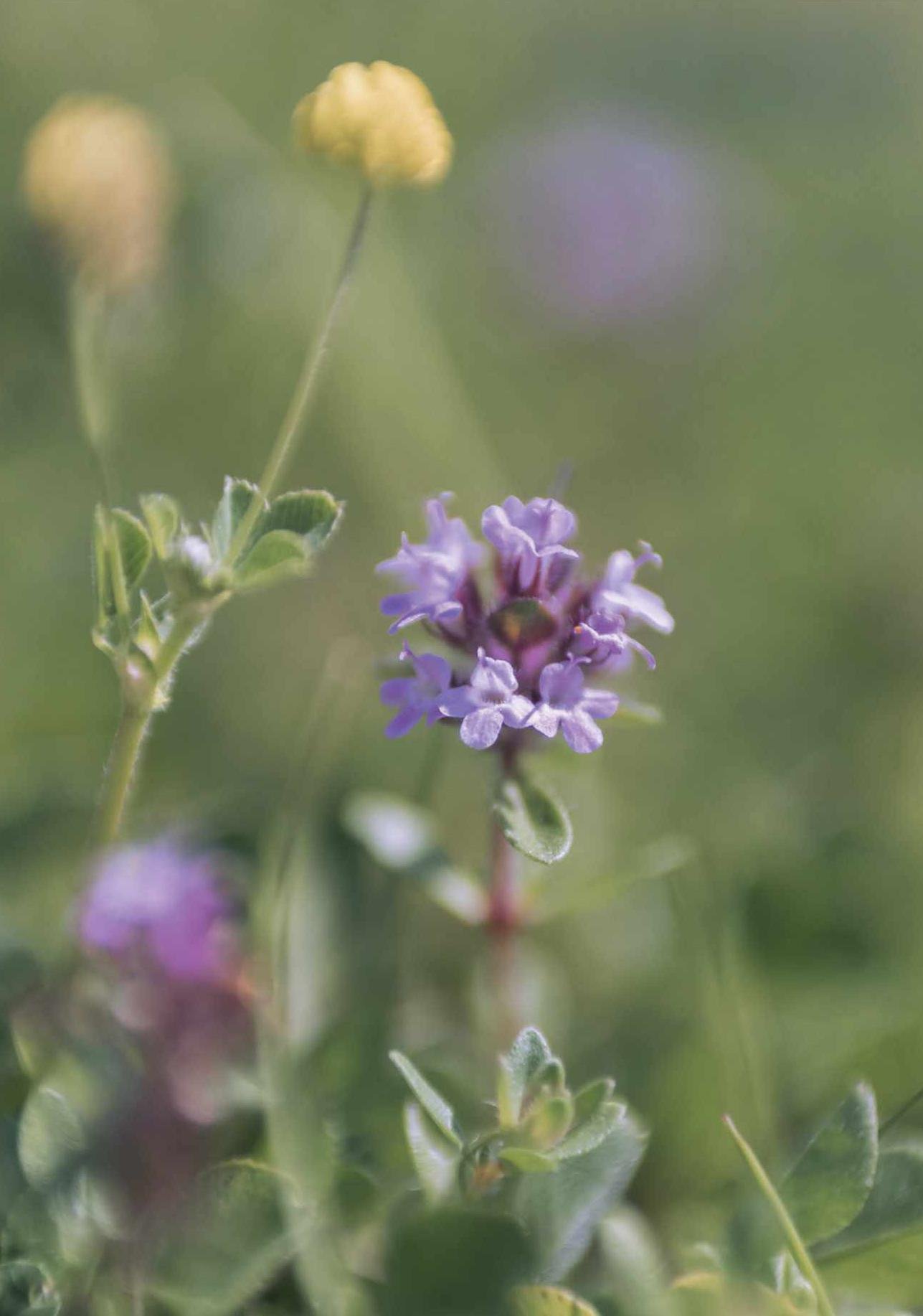

Jo Stephen’s ethereal images celebrate the beauty of wildflowers – and remind us how vital it is to protect them

It’s a sunny early summer’s day and I am sitting in a meadow listening to the chirping of grasshoppers and crickets, the songs of skylarks and stonechats and the buzzing of insects flitting between the wildflowers.

Time almost seems to stand still as I watch the daisies and grasses sway in the breeze through the camera viewfinder. Whatever is going on in the wider world, all the worries that I carry around with me, all slip away in this moment of simple connection and stillness. It is then that I release the shutter and take my photograph.

WHY FLOWERS?

Wildflower photography accounts for a large body of my work. While I also enjoy creating images of habitats and wildlife, it is our native plants that really capture my imagination. There is an incredible diversity of form, colour and texture within the botanical realm, which is a joy to explore and capture as a photographer.

Plants are fundamental to life on the planet – their ability to turn sunlight into energy and create the atmosphere we breathe and the food we eat never ceases to amaze me. We are so connected to the wonderful world of plants.

As organisms that are unable to run away when in danger, or to travel to find a mate, plants have evolved with amazing and beautiful adaptations to meet these needs. The myriad flower forms and colours designed to attract pollinators are some of the most delightful, but travel to the heaths and there are glistening sundews ready to trap small insects in their bejewelled leaves and coconut-scented gorse with exploding seed pods. In the woods, pale, ghostly plants such as bird’s-nest orchids and toothwort, which don’t produce green-coloured chlorophyl to photosynthesise, parasitise the roots of trees and steal nutrients. I find the diversity, resilience and adaptability of wildflowers incredibly beautiful.

I have always loved photography and nature. The two came together in earnest following a serious illness almost a decade ago. During my recovery, I would walk in the fields and woods around the village with my camera, and wildflowers became the subject of most of my imagery.

“I would walk in the fields and woods around my village with my camera”

I live in a little village outside the market town of Blandford Forum in Dorset. On the edge of the Blackmore Vale, it’s an area characterised by arable and dairy farming, forestry and chalk downlands with the river Stour meandering through the valleys fed by small chalk streams. I create almost all my work within a few miles of my home, and each walk still brings new discoveries and encounters, even in the depths of winter. Photographing in the same places, following the seasons through the years, has given me a connection to the land as well as a sense of belonging.

Staying local enables me to keep the carbon footprint of my photography to a minimum and by revisiting sites I can discover plants that may have gone unnoticed before, or I even notice the absence of certain wildflowers.

CONSERVATION BY CAMERA

I think of myself as an artist – but also as a nature conservationist. I want to do whatever is in my power to help see nature protected and restored. I believe that unless we get to know the natural world around us, we won’t fight to protect it. I think sharing imagery of wildflowers acts as an invitation to get to know them better, and often others respond by sharing images of the wildflowers they know.

Photographing plants is a great way to get to know them, learn their names and begin to build an understanding of their habitats and their roles in different ecosystems. A lot has been written about both ‘plant blindness’ (our inability to recognise many of the plant species around us) and ‘nature deficit disorder’ (our lack of connection to nature). Wildflower photography addresses these issues and fosters a love of the botanical, which I hope promotes conservation.

As summer drifts into autumn, it is time to encounter late-flowering species such as autumn lady’s tresses, a beautiful native orchid that grows on the chalk downlands and ancient hill forts here. It’s also one of my favourite times to walk in the local ancient wood pasture, where the last of the harebells and field scabious will still be in bloom under trees laden with berries, hips, nuts and fruits, and the colourful grassland fungi will be starting to appear, too.

HOW TO PHOTOGRAPH FLOWERS

1 Shoot from ground level to create intimacy with your subject. This invites connection and illustrates the niche a wildflower occupies.

2 Create a shallow depth of field by using a wide-open aperture; I like to shoot between f/1.8 and f/3.5. This will separate your subject and blur the background (known as bokeh).

3 Soften images by holding found objects, such as fallen leaves and petals, up against your lens to act as a filter. Or create interesting effects by holding ferns or leaves up to your lens as they will cast shadows in the blurred background of your image.

4 Shoot through foliage for creative blur effects. To maximise this, I often shoot towards the sun at about a 45° angle through foliage. Shooting after rain, or with the morning dew on the ground can create bubbles and rainbows.

5 Use selective focus to sharpen the details you wish to draw your viewer’s eye to.

Jo Stephen is a nature photographer who lives in rural north Dorset. Her work is informed by her love of the wild. jostephen.photography