Tall and elegant, the English elm once graced our countryside in its millions, until disease struck it down. But all is not lost. Conservationists now hope the elm will be reborn, thanks to the work of scientists and volunteers, discovers Rob McGowan

Chiffchaffs chirped, Pevensey Castle’s blue and yellow flags fluttered in the spring sunshine, a breeze rustled the bare branches of a stand of tall trees – and all seemed well in this corner of Sussex.

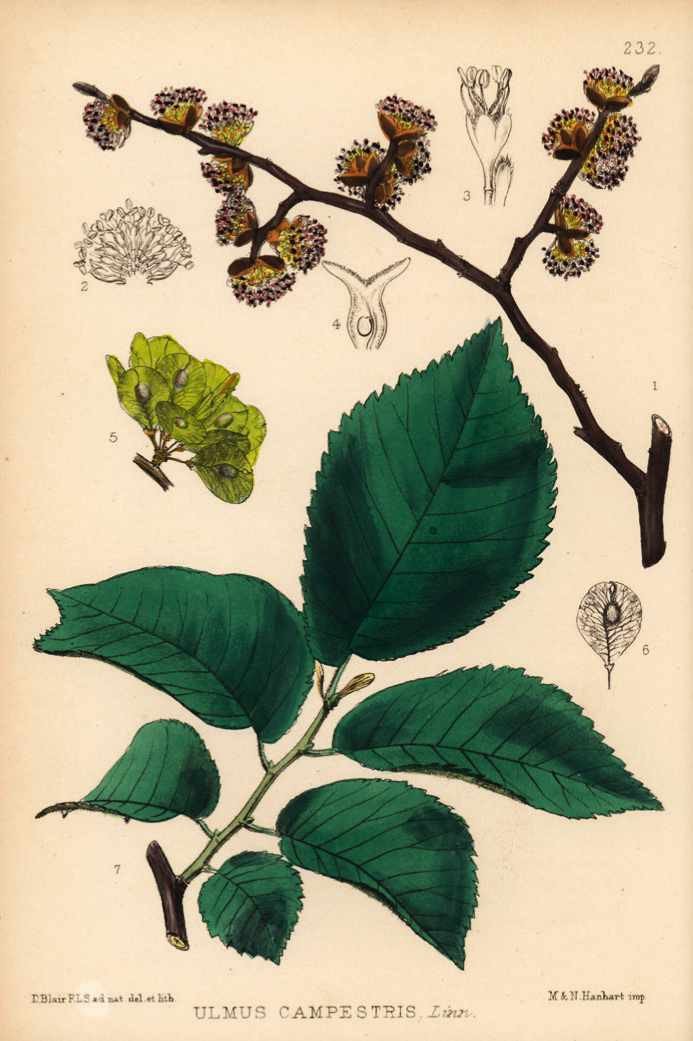

Those tall trees are English elms, Ulmus procera – an iconic species that once stood sentinel across Britain’s lowland landscape, their straight, slender trunks and billowing, thundercloud-like canopies immortalised by countless artists and poets. In folklore, elms often had a sinister, rather Gothic reputation, as they were associated with death, partly because of their habit of suddenly shedding branches.

For centuries, elm wood was prized for its toughness and beautiful swirling grain, and fashioned into everything from flooring to furniture, cartwheels, tools and coffins. Because elm holds its shape and strength when waterlogged, it was often used in ships’ keels, lock gates and water wheels. Elms were also renowned for the ecosystems they supported, including 80 species of invertebrate, notably the white-letter hairstreak butterfly and myriad moths.

“Their billowing canopies have been immortalised by countless artists and poets”

However, the elms that framed Salisbury Cathedral in John Constable’s famous 1823 landscape are long gone, decimated by waves of Dutch elm disease (DED). By the late 1970s, around 25 million trees had perished and the species had largely slipped from the collective memory. But not entirely. Like Asterix’s Gaulish village, the English elm clung on, unheralded, in a few areas. Parts of East Sussex remained a stronghold: a slice of coast and countryside between Brighton and Pevensey. The combination of sea breezes and the largely treeless South Downs may have created an area that the elm bark beetle, which spreads the disease, could not access in large numbers.

THE PLAGUE RETURNS

Anthony Becvar is a tree health officer at East Sussex County Council (ESCC); a large part of his job has been to protect the elms, which are now globally significant. During the winter of 2011, Becvar and his colleagues set out in search of the remaining mature elms, walking for miles along footpaths and byways. They counted about 14,000 and plotted them on a map. Since then, however, the team has had its work cut out. Dutch elm disease has burst into the “control zone”, entering from the north, Becvar thinks, and moving along the Ouse and Cuckmere valleys, facilitated perhaps by a succession of unusually warm springs.

Becvar says the elms haven’t been re-mapped and he’s reluctant to Diseased elms reveal themselves in late spring, when new leaves appear brownish and curled. Initially, the ESCC team would fell diseased trees as soon as they were spotted so they didn’t decline and become breeding grounds. But with greatly reduced budgets, ESCC has prioritised felling trees considered to be in an ideal condition for beetles to breed.

“As the disease is endemic,” Becvar says, “we are never likely to eradicate it. However, my main task is to ensure a population of healthy elm continues within the control zone. By removing trees suitable for breeding beetles, we hope their population diminishes enough to allow regrowth to a point where there will always be a healthy mature population. I am optimistic that this is possible if enough time and money is spent seeking out diseased trees and removing them in a timely fashion.”

“Diseased elms are daubed with ominous orange spots, then dismembered”

THE MIGHTY HAVE FALLEN

The rasp of a chainsaw, shouted commands, the grating of branches hauled along driveways, the grind and deathrattle of woodchips clattering into a trailer’s housing. These have become familiar sights and sounds across Eastbourne in recent years, as tree surgeons battle with the fallout from two microscopic fungi: Ceratocystis ulmi, cause of Dutch elm disease, and Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, the cause of ash dieback. Their wind-borne spores have decimated swathes of ash woodland at the edge of town and beyond.

Victorian town planners favoured elms in seaside resorts such as Eastbourne, Seaford and Brighton, as they thrived on the chalky, alkaline soils and were known to be tolerant of salt-laden air. More than a century later, mature elms still line many of the broad streets.

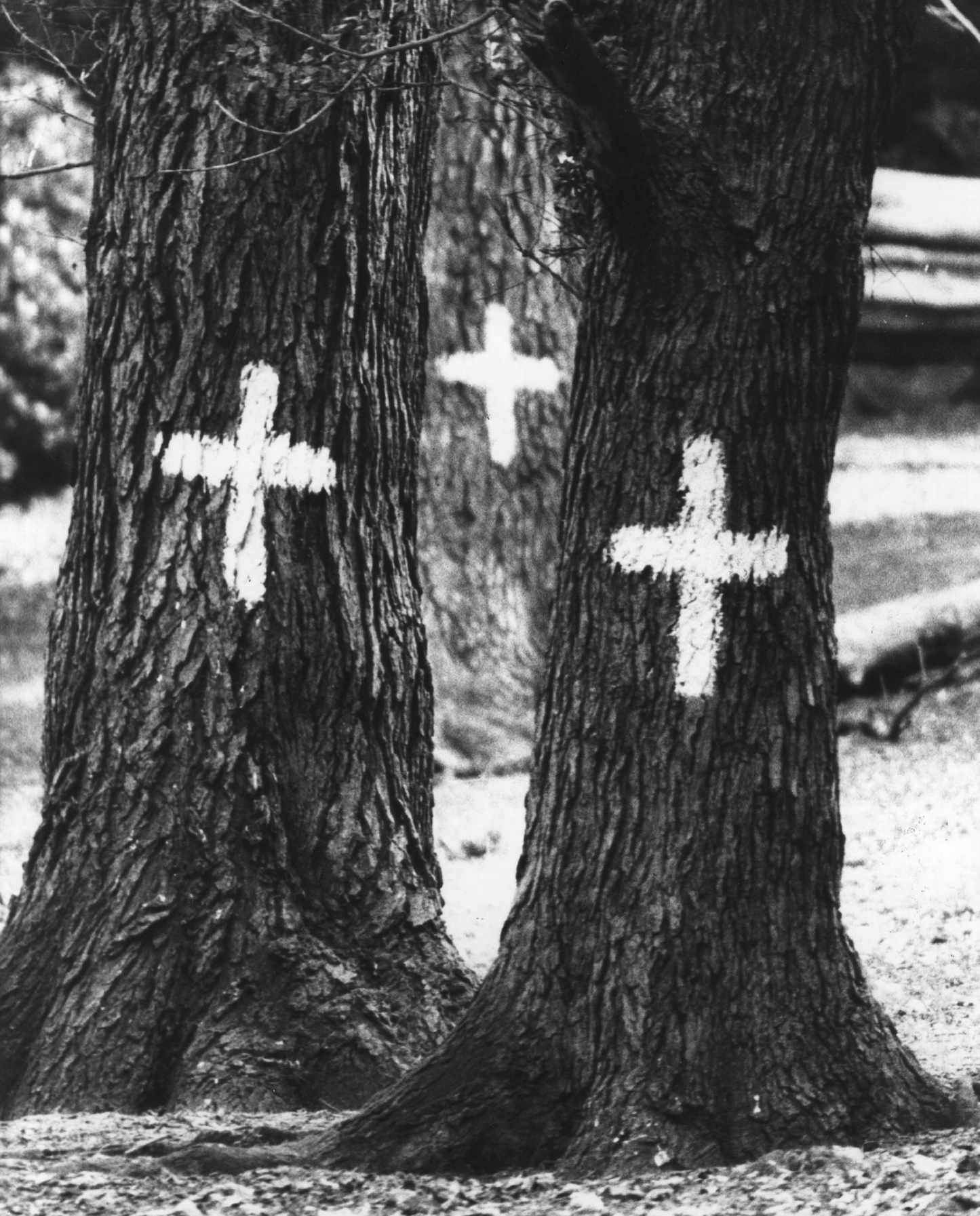

The elms are probably living on borrowed time, though. In Eastbourne, diseased street elms are daubed with ominous orange spots, then dismembered – boughs and branches sliced off and de-barked. For a while, a towering trunk will remain at the roadside, before being sliced again, leaving a stump – scored vertically and ‘girdled’, with conducting tissues severed to prevent the fungus reaching the root system. Some suburban roads are now adorned with dozens of elm stumps, at times to the dismay of residents. Removing them is apparently more costly than felling the bulk of the infected tree. In places, locals have placed flower baskets atop the stumps, or invited sculptors to get imaginative.

In Brighton, which has long taken pride in its large and diverse collection of around 17,000 elms and a strictly enforced “cordon sanitaire” since the 1970s, the local authority is also dealing with a resurgence of DED. The death in 2019 of one of the famous ‘Preston Twins’ – elms that graced the city’s Preston Park for more than 400 years – was widely mourned.

HOPE FOR A NEW GENERATION

But all is not lost. When 50 elms had to be felled at Coldean Wood in 2021, Brighton and Hove Council swiftly replaced them with elms of new disease-resistant varieties.

The long-term future of elms will clearly rely on trees that are resistant to DED. Efforts have been underway to propagate disease-resistant hybrids for many years, with varying degrees of success. Most of the hybrid cultivars have Asiatic ancestors – such as the Himalayan elm – that are naturally resistant to DED. But environmental conditions in Asia are often very different to those in southern England.

“More than 11,000 saplings were planted on the South Downs this winter”

Andrew Brookes has taken on the painstaking task of testing which hybrids will prove to be resistant and thrive in English conditions by growing them at five sites near Portsmouth. A butterfly conservation specialist, he was especially keen to discover which of the cultivars would prove to be a viable habitat for the rare white-letter hairstreak butterfly. “It’s a slow process,” he says, “with occasional advances, but also tragedies and setbacks.”

A Dutch/French hybrid elm known as Lutece, now propagated in the UK, ticks many of the boxes: disease resistance, insect habitat, tolerance of waterlogging and drought, and resemblance to the native elm. Brookes is also enthused by the elm variety ‘Ademuz’, derived from a highly resistant natural European elm recently discovered in Spain. But he points out that it has become almost impossible to acquire because of new import regulations, linked to attempts to prevent the spread of the destructive bacterial disease Xylella fastidiosa, which affects various species, including olive trees.

FRESH START FOR THE ELM?

A fine spring morning, with wide skies and a commanding view to the English Channel. A group of volunteers are wielding sharpened spades, slicing into the crumbly, chalky soil of a hillside above Eastbourne, and planting hundreds of trees. A local charity, Treebourne, is overseeing the mass planting of a range of saplings in urban and rural settings, including hundreds of the disease-resistant New Horizon elms, grown in the UK by Hillier Trees. Supplied by South Downs National Park, the elms are part of its ambitious Trees for the Downs campaign, now in its third year. More than 11,000 saplings were planted this winter, which will rise to a total of around 100,000 new trees in five years.

Freshly planted, these whip-thin saplings tremble in the breeze. Could they be the beginning of a resurgence of the elm, not only in this enclave, but well beyond? Experts are cautiously optimistic that, with luck, these elms may be the beginning of a comeback.

The elm plague

First recognised in France after the First World War, Dutch elm disease reached England in 1927 and swiftly killed thousands of elm trees. The microscopic fungus blocks a tree’s vascular system, causing leaves to wither, branches to wilt and usually death within a year. It is spread by tiny (3mm) elm bark beetles, Scolytus scolytus, which burrow beneath the bark of newly deceased elms to lay eggs – and in so doing gather fungus spores. Emerging in spring, the young beetles fly to nearby healthy elms to feed, infecting them.

The original epidemic mysteriously declined in the 1930s, but a second one took off in 1967, emerging from shipments of rock elm from Canada. This time, elm bark beetles carried a far more virulent strain of the fungus and within a decade around 90% of the distinctive English elm – some 25 million trees – had perished.

Rob McGowan is a journalist and editor based in Eastbourne, who has a background in geography and environmental economics.