Discover Assynt

Embark on a walking, fishing and wildlife-watching adventure among the mountains and lochs of this enchanted region of northern Scotland

It isn’t catching my first brown trout that I’ll remember best. It isn’t the otherworldly cragscapes. It isn’t the birdsong or the convivial evenings in the local harbour bar. It is a single distant view across a serene loch.

I was sitting in a rowing boat far out in the water when I spotted snake-like heads above bejewelled necks: three majestic divers patrolling like ships of war. Something about their primordial poise, their utter sense of belonging set against the rugged, distant loch shore is fixed in my memory.

They were black-throated divers, birds I had never seen before. In a landscape I have long dreamed about but that had taken me almost 50 years to get around to visiting.

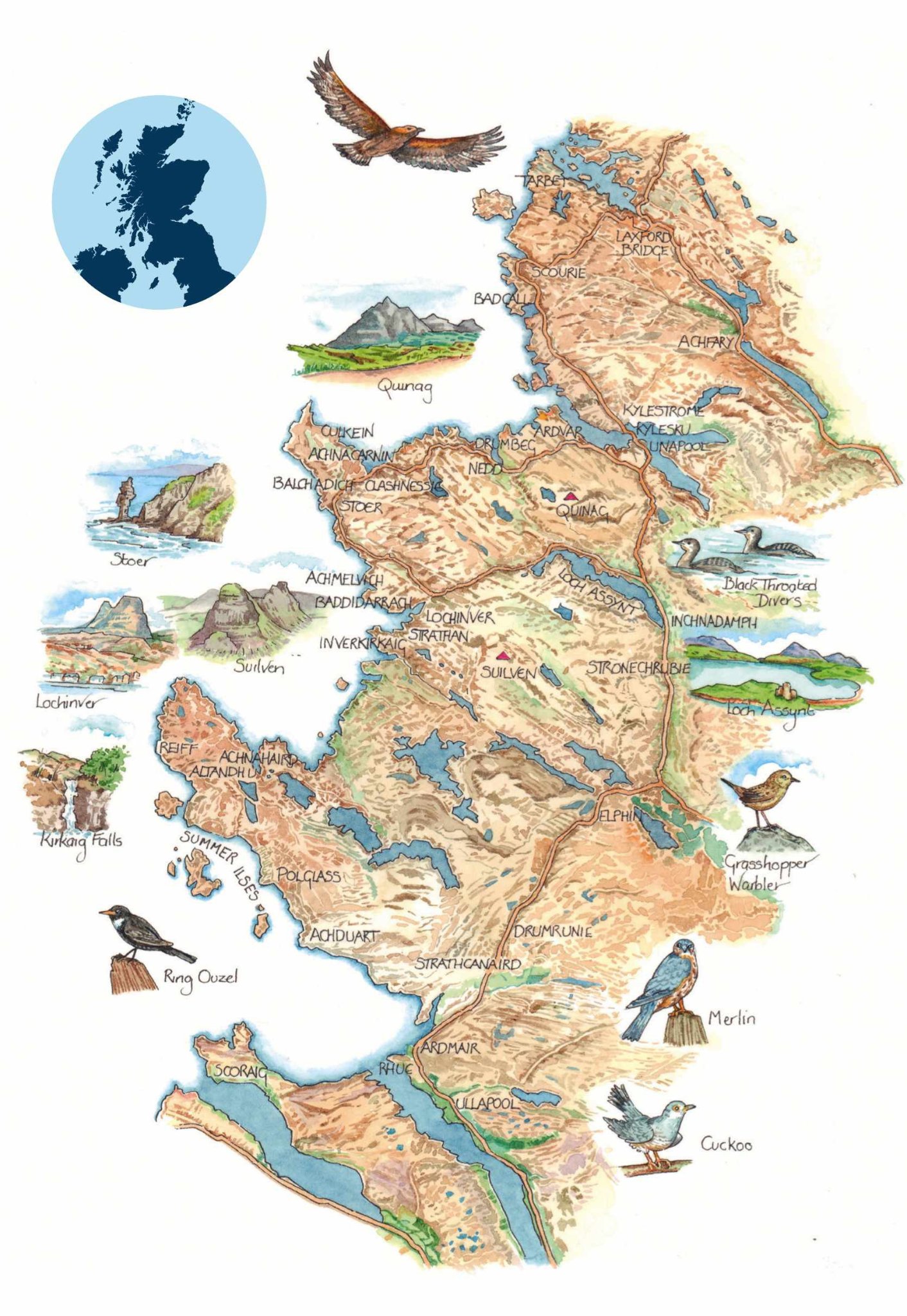

It was my friend Gavin who signed me up for adventure in Assynt. He is a fly fisherman and seeker of places far from human bustle. Much delayed by Covid, I finally made it there, arriving on a June evening. The last two hours of road, from Inverness to Lochinver, over firth, through forest, under mountain crag and, finally, along the shores of Loch Assynt, felt like a release. Settlements dwindled along the way, the peaks rose and the sweeping road became a Top Gear presenter’s fantasy.

Assynt and Coigach is a rugged region of Sutherland just north of Ullapool. It harbours hundreds of lochs, legendary mountains and coves of silver sand. And a tiny human population. The human story is a big one, however. Like much of Scotland, the land is divided among a handful of major landholders after suffering unforgiveable clearances in the 18th and 19th centuries. But fortunes were partially reversed in 1993 when the Assynt Crofters Association bought the North Assynt Estate, enabling “ordinary people who live and work on the land to have some control over their own economic future” (see box, page 22). While crofting continues, tourism is an important source of revenue, especially from those who come to fish the lochs for brown trout. And that was our chief reason for coming there.

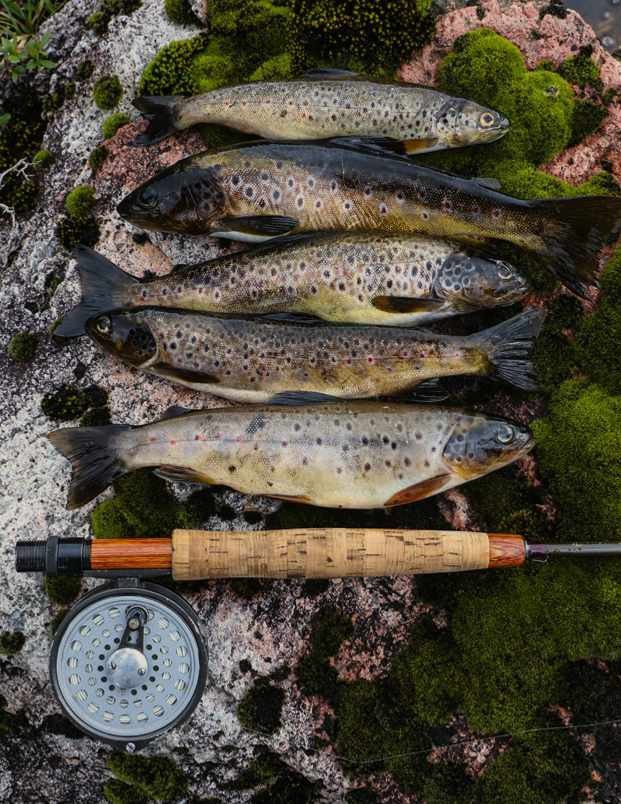

I am not a good fly fisherman. It is a balletic art of rhythm and timing and release. A good proponent, such as Gavin, can cast so the line and fly kiss the water’s surface, tempting the shy fish. But I was drawn by the prospect of taking a boat on to a remote loch and exploring at diver-eye level. In Assynt, you buy a fishing pass and hire rowlocks so you can use the boats found on the shores of the larger lochs. This done, you follow the relaxed instructions: “Park by the side of the road and walk for an hour or two along heathery, rushy tracks to reach the loch.” These walks are thrilling, the nature hit overpowering. Grasshopper warblers reel from scrub, orchids bloom in their thousands among countless unfamiliar wildflowers. A merlin might shriek from a crag, hunting meadow pipits. And, all the time, cuckoos. I’ve never heard so many. Loch Crocach was where we saw the divers. It is a huge body of water, with fjord-like bays and studded with wooded islands. With Gavin and another friend, Joel, we rowed and fished and pottered ashore for lunch. And sometimes we just drifted across the loch. Every raven sparked us into eagle-goggling mode. Assynt has several pairs of golden eagles but they are recluses. Cuckoos serenaded us the whole day from the islands. And we did catch some fish – me, not many. The wild ‘brownies’ are incredibly beautiful bars of ancient silver-gold, each with a unique spotted pattern. We took a small number home for our supper. Fried in butter, they were utterly delicious.

GO FISHING

Fly fishing is a fascinating way to experience Assynt. The act of fishing seemed to immerse me even deeper in the landscape. I was lucky to have a friend and mentor to show me the fly-fishing ropes, provide me with some kit and take me to the best locations. Fly-fishing kit is the simplest set-up of all. You just need a rod, line (flyline and leader line) plus the fly. We largely used wet flies, which sink beneath the water rather than rest on it.

If I were heading to Assynt on my own, I would contact expert fly-fishing guide Stewart Yates; assyntflyfishing.com

FREEDOM TO ROAM

Like most of Scotland, the landscape is open to wander. It’s a deep feeling of surprising relief to explore off-track, untrammelled by footpaths or assaulted by “keep out” signs and hostile fences. One special day, under moody skies, we walked in from the small township of Stoer deep into an area of crags and heather and lochs, where water and land dance around each other. It felt mildy dangerous: Loch nan Lub, Garbh Loch Mòr and Loch Poll Dhaidh, eerie, beautiful places that seldom see people. Surrounding crags occasionally part to reveal the bigger peaks – Quinag, Canisp, Suilven. But the feverish shape of the lochs and the sheer brooding presence of wilderness made me feel small. It’s hard to express just how impressive our forebears must have been to eek a living out here – though there is little sign of any human activity, save for an occasional sheep.

As the afternoon turned its thoughts towards evening, we heard the deliciously chilling “whau-oooo” of the black-throated divers. It felt like a warning, a reminder to us to check map and compass and keep an eye on time and weather.

“The feverish shape of the lochs and the brooding presence of the wilderness made me feel small”

DAWDLING AMONG WILDFLOWERS

On that walk, we fished. But the best walk I’ve taken in Assynt was without rod in hand when we set out to conquer Suilven. This mountain is actually small, just 731m (Pen y Fan in my Brecon Beacons home is 886m) but has a ferocious Sphinx-like appearance and you climb pretty much all of those 731m in one go. Even before you start, it’s a twoand-a-half hour walk through Glencanisp to the foot of Suilven; an undulating stroll from the wooded sanctuary of Glencanisp Lodge, where redpolls and siskins hog the birdfeeders. Burns and shallow reedy lochs flank the path, with the great peaks of Canisp and Suilven ever-present, their heads drifting in and out of cloud. I dawdled among the wildflowers and strange calls of sandpipers and greenshanks and curlews. No doubt there were eagles watching us.

The final climb up Suilven is a steep, rough stair. You need to use your hands. It took me about 30 minutes, but there’s no respite at the top of the ascent. I arrived on a narrow ridge, a void opening up to reveal a breathstealing vista south of lochs, peninsulas, islands and distant mountains, including the sawn-off silhouette of Stach Pollaidh. I swooned with vertigo that was only partly assuaged by the arrival of two ring ouzels, calling loudly around my head.

“Forced from the land, people faced either starvation or virtual slave labour for landowners”

Suilven’s peak requires a further clamber and negotiation of tight ledge. I struggled. It was a long way down. But the peak itself is a cricket pitch-sized plateau and the place to lunch, gawp and try not to think about the climb down. There is a curious drystone wall, built here some 160 years ago and still standing proudly. Called the ‘famine wall’ or ‘destitution wall’, it is a bleak reminder of the Clearances. After being forced from the lands, people faced either starvation or virtual slave labour for landowners in return for food, often working on projects with no purpose, such as this bizarre, mountain-top, wall-to-nowhere. It does, at least, offer climbers a respite from the elements.

COMMUNITY OWNED

Much of the landscape that I’ve described in this article is part of the 8,500-hectare North Assynt Estate, which was bought in 1993 by the Assynt Crofters’ Trust. Previously, it has been in the long-time ownership of the Vestey family, before it was sold to a Swedish property company in 1989. The company went into liquidation and the future of the land became a major worry for the local crofters. They banded together and fought a highly effective campaign to raise money to buy the land – for £300,000 – within six months. The land is now managed by a committee directly for the benefit of the local community and includes farming, tourism, fishing and a hydro-power plant, which was installed in 2000. The Assynt Crofters’ Trust’s actions have been a model for other community buy-outs in Scotland and beyond.

OUT OF THE WILD, INTO THE WARM

Climb down we did – as the weather began to close in. The eight-mile walk back to Lochinver was quite the reward. It’s safe to say our conversation was less sparkling – and my wildlife spotted less acute. But the sense of achievement was worth the pain.

The weather does close in often in Assynt. Even on a mid-June day. We spent a day walking up the excitable River Kirkaig to reach the beautiful Fionn Loch; the Falls of Kirkaig along the way are among the most spectacular in Scotland. It began raining, swelling the falls further. And when you spend five hours in the rain, there are no boots or waterproofs that can keep it out. There comes a point where you simply can’t get any wetter and we ploughed on. But even on a spring or summer’s day, wet and wind can spell problems. We scuttled back to Lochinver, glad of the birches, hazels and oaks that offered blissful respite further down the glen.

Sometimes it feels as if the rain and wind exist purely to exalt that moment when you step inside a bar or café at the end of the day.

It’s never a bad idea to grab a celebratory dram in the aptly named Wayfarers’ Bar in Lochinver. It’s where some of the locals, offshore workers, salmon farmers and others gather – offering some insight into how people make ends meet here.

After a day in the wilds, Lochinver is a metropolis, a warming haven where red deer wander down the main street and eiders patrol the harbour. The local Sutherland accent is soft and lilting, a satisfying contrast to the rugged surrounds. Once settled in, I found it exquisitely difficult to peel myself away and off to bed.

In two extended visits, I have scratched only the veneer of Assynt. But it has broadened my idea of what Britain really has to offer. I’m telling you all of this in the hope you will visit, immerse yourself in landscape, help the local economy and report back on what you find. And may that distant speck in the mountain-propped sky be a ‘goldie’.

Fergus Collins is editor of BBC Countryfile Magazine and host of the Plodcast.

He is looking forward to a third visit to Assynt this spring and uncovering more of its secrets.

NOW EXPLORE ASSYNT FOR YOURSELF

Where to stay, visit, eat and drink by Fergus Collins

STAY

We used Scottish Cottages and found inexpensive accommodation near Lochinver even in high season, such as An Sealladh. scottish-cottages.co.uk/highlandsandislands

Go to Discover Assynt for wider options for B&Bs, campsites and hostels. discoverassynt.co.uk/holidayaccommodation-assynt

BUDGET

Achmelvich Beach Youth Hostel

Sits beside a beautiful sheltered beach with a limited number of rooms. From £31 per night B&B. Dog friendly. 01571 844 480

Lochinver Bunkhouse

A modern, cosy hostel in the heart of Lochinver with an onsite café. 01571 844 598

GETTING TO ASSYNT

Unless you live in Inverness, Assynt is a long way. You can fly to Inverness from London or Bristol (easyJet) and then hire a car. It’s a pleasant two-hour drive from Inverness to Lochinver. Or take the Sleeper train from London Euston to Inverness. sleeper.scot I’ve driven from Manchester to Lochinver – ajourney of shared driving that takes, conservatively, nine hours when you add stops for food and leg stretching. Alternatively, take a campervan and make the journey part of the adventure.

PODCASTS

You can hear four podcasts that Fergus recorded in Assynt. Find the BBC Countryfile Magazine Plodcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and all good podcast providers and listen to the following episodes:

108 Taking a boat on to Loch Crocach.

115 Climbing Suilven.

151 Foraging and fishing in Assynt.

166 Exploring Handa Island.

WET DAYS IN ASSYNT

Ullapool

Settled comfortably on a peninsula in Loch Broom, this lovely town has a grand variety of eateries, bars, cafés and shops to while away a drizzly day. Tweed and whisky rub shoulders with some good food shops. A pint while watching the ferries is a hugely recommended pastime. The birdlife is never dull. Don’t be seduced by the prices in the estate agent’s window.

ADVENTURES FURTHER AFIELD

Handa Island

Managed by the Scottish Wildlife Trust, this small island offers a thrilling day trip to see vast seabird colonies, seals, wildfowl and colonies of skuas across the inland moors.

Achiltibuie peninsula

Just south of Assynt and Crocach is a ruggedly gorgeous and remote peninsula with stunning beaches, such as here at Achnahaird.

WHERE TO DRINK

Wayfarers’ Bar, Lochinver

Right on the harbourside, this is a friendly, no-nonsense bar with 100 single-malt whiskies. Food is solid and filling, perfect when you need to dry off outside and wet your inside.

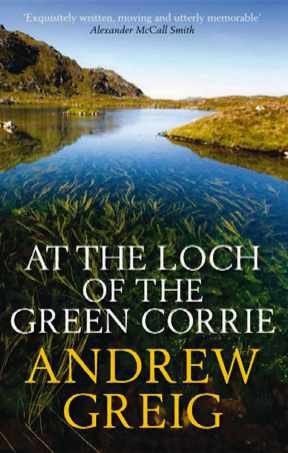

WHAT TO READ

At the Loch of the Green Corrie

by Andrew Greig

An angling adventure in Assynt, a memoir of friendship and a celebration of the poetry and life of Norman MacCaig, who loved this landscape.

WHERE TO EAT

Lochinver Larder

Lochinver has fine eateries but this is my favourite. Lochinver Larder’s magnificent pies won ‘Best Scottish meat pie’ in the British Pie Awards 2022. They are delicious – all of them. Take them into the hills for a picnic treat. lochinverlarder.com

Kylesku Hotel Bar

This lovely hotel sits at one end of the Kylesku Bridge and offers an unbeatable view over Loch Glencoul and a great place to sample local seafood. We watched seals, peregrines and divers from the veranda. kyleskuhotel.co.uk

Seafood Shack, Ullapool

Worth queuing for. The menu changes daily but the unbelievably delicious seafood served with charming informality is refreshing. It’s not a 100% authentic experience unless you eat your lunch in drizzle. seafoodshack.co.uk