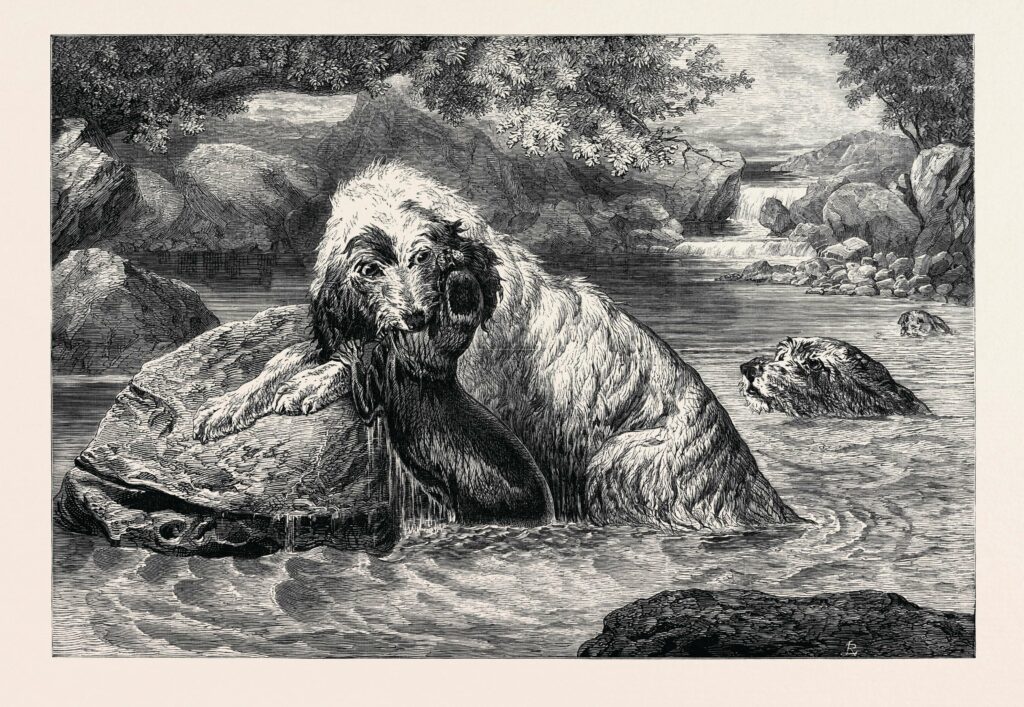

With their webbed feet, supersensitive noses and abundant energy, otterhounds were perfectly adapted to track their prey, but the dog is now disappearing in Britain. Lucap Rolant asks, can they survive?

Have you ever seen an otterhound? Appearing in many different colour combinations – wheaten, sandy, black, blue, tan, liver, grizzle and white – this playful breed is friendly, energetic and affectionate, with a bearded face and drop ears hanging down the side of its head. Its big personality matches its size, with male otterhounds weighing up to a hefty 52kg, compared to a golden retriever at around 30kg.

But despite its good looks and conviviality, the otterhound today is a rare sight and at risk of becoming extinct. Otterhound numbers worldwide are only in the hundreds. In the pandemic puppy boom of 2021, a record-breaking 349,013 puppy births were registered – but just 42 were otterhounds. And by late 2022, only 14 otterhound puppy births had been registered, compared to the most popular breed, the Labrador retriever, with 61,559 puppies recorded. Small wonder that the Kennel Club describes the otterhound as “one of the rarest of all the vulnerable native dog breeds”. So why the decline? The answer, it seems, is fashion.

Bill Lambert, spokesman for the Kennel Club’s Save Forgotten Dog Breeds campaign, explains. “There are more than 200 dog breeds in this country, each with different personalities, characteristics and needs, and yet people are increasingly opting for the fashionable or obvious choices. Sadly, it seems that TV, celebrities and social media – rather than responsible research – are normally the guiding force behind our choice of dog, and which breeds move in and out of fashion.”

The Kennel Club’s aim, says Bill, is to maintain “a rich diversity of breeds, so that people can get a dog that is truly right for them. One of the main reasons there is such a decline in popularity of these dogs is because people simply don’t seem to know of them.”

HUNTING HISTORY

The history of otterhounds is inextricably entwined with the once-traditional pastime of otter hunting. During the Middle Ages, otter hunting was popular among England’s royalty and nobility, with packs of otterhounds attached to royal households.

In those days, otters were seen as nothing more than vermin, perhaps, in large part, because they competed with humans for fish. However, these intelligent, semi-aquatic mammals were formidable opponents during the hunt, and required a versatile breed to overpower them.

Otterhounds were originally bred as otter-hunting scent hounds – dogs that hunt via scent more than sight. Their water- and weatherproof coats, webbed feet and love of swimming made them ideally suited to tracking down otters along rivers and in other wetland habitats.

According to Ayrshire writer and dog expert Robert Leighton, to outwit the otter, otterhounds needed: “A bulldog’s courage, a Newfoundland’s strength in water, a pointer’s nose, a retriever’s sagacity, the stamina of a foxhound, the patience of a beagle and the intelligence of a collie.”

In fact, breeders suspect that the otterhound’s ancestors include five redoubtable hunting breeds: the bloodhound, foxhound, southern hound and two venerable French breeds: the griffon Nivernais and grand griffon Vendéen. The Kennel Club notes “a look of French hound ancestry” in the otterhound’s head and expression. The current otterhound breed can only be traced to the early 1800s, with some speculating that Britain’s earlier otterhounds, such as the “otter dogs” referred to in Izaak Walton’s classic book The Complete Angler (1653), were in fact the now-extinct southern hounds.

MODERN CAUSES OF OTTER DECLINE

Hunting alone did not cause the decline in the otter population. Conservationists believe three other factors lay behind the decimation of otter numbers: the use of harmful chemicals by industry and agriculture was the primary cause, with loss of habitats and declines in fish populations also contributing.

After hunting was outlawed, and some of the chemicals most harmful to otters were banned, otter populations thankfully revived. However, the most recent large-scale UK survey data (from National Otter Survey Wales, published in 2021) suggested an unexpected downturn in otter numbers across Welsh river catchments. Dr Liz Chadwick from Cardiff University Otter Project (CUOP) suggests that this should be a wake-up call for otter conservation, highlighting the state of Britain’s freshwater ecosystems.

Pollution and changes in fish stocks may both be important – CUOP is researching freshwater chemical contaminants and gathering evidence to identify other potential causes for the decline. A national otter survey is currently underway in England, coordinated by the Mammal Society.

OVER AND OUT

From its peak in the Middle Ages, otter hunting continued into the 20th century – in 1953, there were still around 16 active otterhounds packs. However, resistance to the bloodsport developed in the late 19th century, when William Lisle Blenkinsopp Coulson, an army officer and prominent member of the Humanitarian League, began a letter-writing campaign to ban otter-hunting. Another campaigner was Harry Hamilton Johnston, a founder member of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire. Otters, argued Johnston, were an intrinsic part of the landscape.

The Humanitarian League campaigned against otter hunting until its dissolution in 1919; later, the League for the Prohibition of Cruel Sports (later the League Against Cruel Sports) campaigned against otter hunting. Objections to, and protests against, otter hunting continued in various forms over the decades, including direct action; hunt saboteurs would lay aniseed oil down to disrupt scent trails and confuse the hounds.

However, when chemical pollution led to the crash in otter populations across Britain and Europe in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, otter hunts were among the first to raise the alarm.

The hunts voluntarily closed in 1976, prior to legal protection for otters in 1978 and an explicit ban on otter hunting in 1981.

As a result of the ban, many hunters disbanded their otterhound packs. Some switched to hunting American mink – the mustelids that flourished in British rivers after escaping from fur farms. However, in 2004, legislation also outlawed the hunting of mink and other wild animals with dogs.

SAVE OUR OTTERHOUNDS

Unlike other hunting breeds, which managed to thrive despite losing their original purpose, with the disbanding of otterhound packs came the decline of the dogs themselves. Today, otterhounds are the rarest of British breeds, unknown to most people. But all is not lost – the Kennel Club’s Save Forgotten Dog Breeds campaign has been raising the profile of the historic native breeds most at risk of dying out.

A key campaign goal is to inform potential owners about these breeds’ personalities and needs, and how they may suit different people and lifestyles. This includes the Discover Dogs area at Crufts, the annual dog show, where people can get to know a range of rare breeds.

“Come and meet these breeds,” urges Bill Lambert, “speak to experts and owners who can tell you everything you need to know, and help us to raise awareness.”

Bill admits that otterhounds aren’t for everyone. “They are an easy-going and goodnatured breed,” he says, “but require more than two hours exercise per day, a larger space due to their size, and grooming more than once a week – so may not be suitable for the fastpaced urban lifestyles of many people.”

Nevertheless, Bill hopes there may be just enough prospective dog owners out there for whom the otterhound sounds like the perfect companion. Could that be you?

FIND OUT MORE

• Visit the Kennel Club for information on breeds and to find out which dog best suits you. thekennelclub.org.uk/getting-a-dog

• Crufts 2023 takes place on 9–12 March at the NEC in Birmingham. crufts.org.uk

Lucap Rolant is a writer from West Wales. The descendant of local princes and mariners, among others, he takes a strong interest in Welsh history, genealogy and folklore.

OTTERHOUNDS: PERFECT PETS?

If their characteristics are suitable for you and your home, you can help save otterhounds from the brink of extinction by keeping one or several. Here are some useful facts about the breed.

• Size: Large (36–52kg)

• Exercise: At least two hours per day.

• Home and garden size: Large.

• City or country? Ideally suited to the countryside.

• Lifespan: Over 10 years.

• Coat: Medium-length double coat – rough, slightly oily and weatherproof; it does shed hair.

• Grooming: More than once a week.

• Feet: Webbed