Born to run

A glimpse of the lightning-bolt that is a running hare is one of Britain’s most thrilling wildlife encounters. Adele Brand takes us deeper into the world of this magnificent mammal

It was the ears that told me. I am under surveillance as I walk a gentle Norfolk footpath on a crisp March morning – so say those black-tipped periscopes that rise from the bright spring green of an arable field mapped by humans, planted with sugar beet by humans.

Hare, a deeply wild creature whose mere presence in Britain is a legacy of people, critiques me across the newborn crops through exquisite eyes of polished topaz. The muscles under black-flecked fur turned gold by the sunshine threaten an explosion of speed should I cross a certain, invisible line. I continue my walk with caution; the hare resumes its meal of beet.

Taking from humans, giving to humans: hares run a jerky course between these personas, cast both as our foil and as quite dependant on our favour. Foremost, of course, they have assumed a side role during Christianity’s most important celebration. It is true that eggs were painted at Easter long before the Osterhase – literally, the Easter hare – crossed the North Sea from Protestant districts of Germany, but in its own country, children were already alert for this magical animal that hid eggs in herb gardens. Oddly, the Leicestershire village of Hallaton independently acquired an ancient hare-related tradition of its own: what it calls a hare pie – which never contained any hare – was flung to a riotous crowd as an annual scramble on Easter Monday.

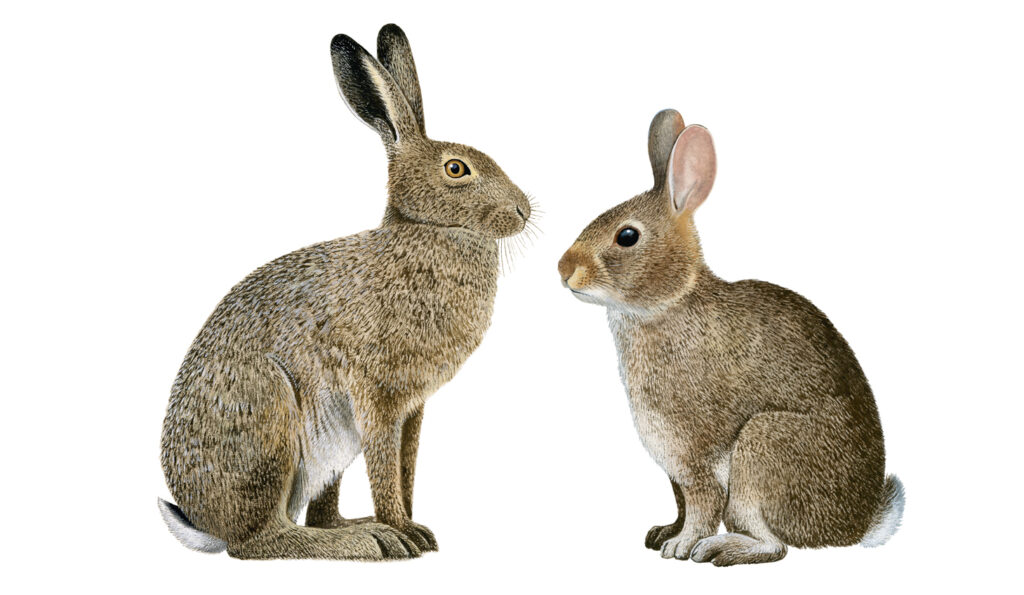

These days, rabbits have stolen the hare’s Easter thunder, and the Osterhase is known universally as a bunny. Distinguishing the real animals is easier than it seems; rabbits are small, highly sociable and dwell in extensive underground warrens. They are rounder, an easier fit for life in a burrow, and move with a scurrying hop that lacks the leggy purposefulness of their open air-living cousin’s angular kicks. But it is the hare’s ears – all 10cm of them, tipped with vivid black as if drawn with a cartoonist’s Sharpie pen – that are the unmistakable trademark.

HARES VS RABBITS

• SIZE

Hares are considerably larger than their smaller cousins and weigh up to 4kg. A large rabbit may be 2kg.

• EARS

Longer and black-tipped in hares. Rabbit ears are more rounded.

• EYES

Rabbits’ eyes are dark while hares have amber- (or topaz) coloured irises.

• LEGS

Longer back and front legs enable the hare to run at speed over long distances.

BOXING AND BITING

Many of my sightings begin with those ears. Hares watch them also; flattened back against the skull, they are a graphic warning. Not social, yet not territorial, hares have most cause to communicate in the spring. Their world is male-dominated – that is, bucks outnumber does, even as embryos. When a doe nears oestrus, a buck guards her, boxing and biting any other males who dare to approach. He urinates on his rear paws and kicks backwards to scent-mark, but the doe will fight him, too, if he courts her too soon. Mad March hares have been a staple of the English language for at least 500 years, and no doubt caught the eye of rural communities long before that.

Yet, the brown hare is not truly native. Outlasting the last glaciation near the Black Sea, it spread across Europe and Central Asia as the temperature warmed – but not to Britain, which was freshly an island and developing habitats too dense for the hare’s liking. Humans changed that equation, opening the woodlands and acquiring skills to deliberately carry other species to new lands.

But the hare stands apart from most animals important in antiquity. Neither a working animal nor eaten by Celtic Britons, it was considered sacred, and a predictor of fate: it is said that Queen Boudica hid one in her dress and released it to ascertain from the direction of its flight how successful her Iceni revolt would be.

FERTILITY AND RENEWAL

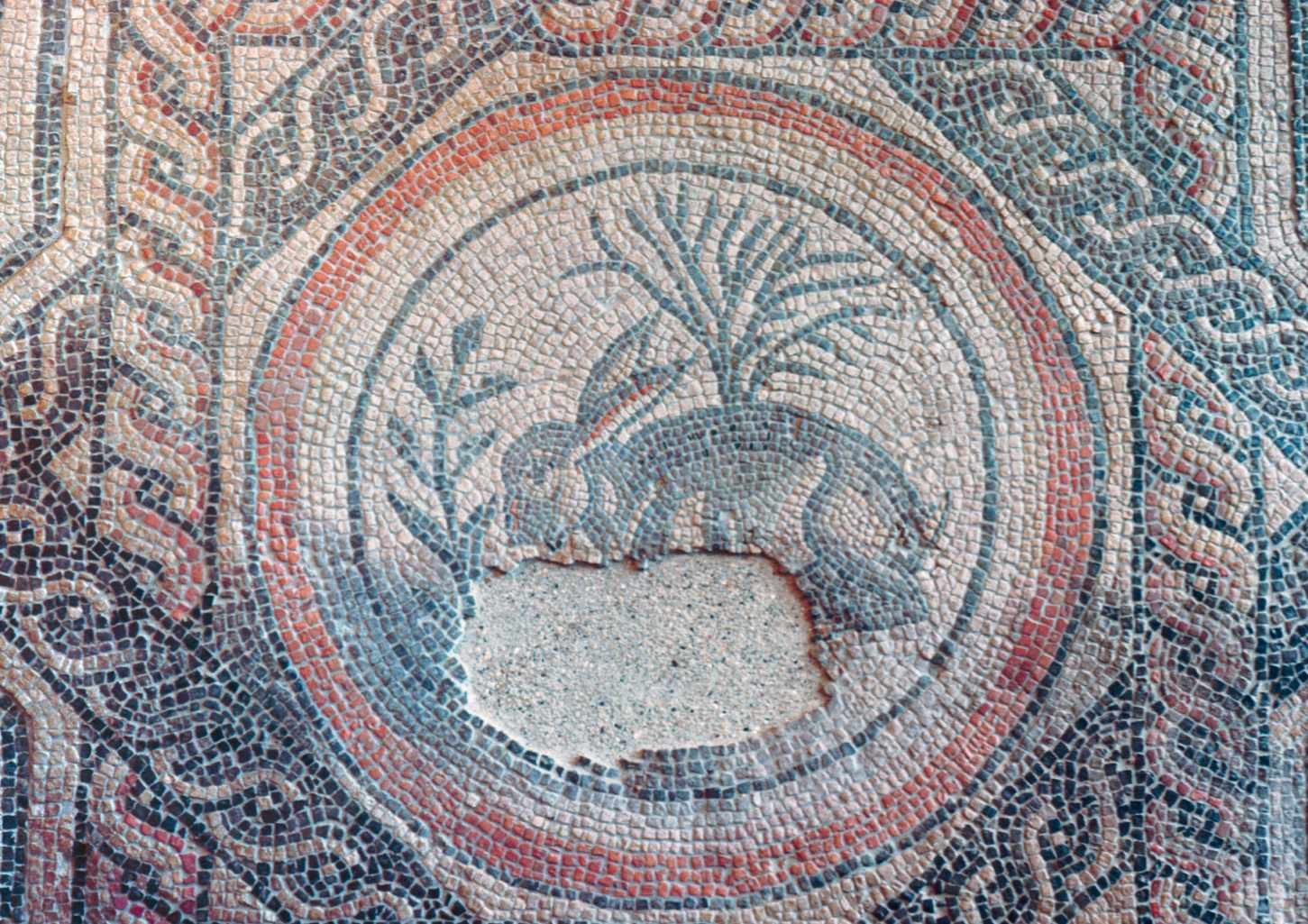

Giver, taker, good luck, bad luck – folklore has never quite decided about the hare. Samuel Pepys carried a hare’s foot which he believed cured him of colic, but death was on the minds of Derbyshire miners if a white hare stared at them while they ate; this eerie creature would lead hapless souls into the darkness, never to be spied again. Romans, despite forsaking Celtic taboos about eating hares, added the species to their own beliefs as a symbol of fertility and renewal. A grazing hare stars in a richly ornate Roman mosaic unearthed in Cirencester, a discovery celebrated in the 21st century by the colourful fibreglass hares on display in the town.

Oblivious, the real hare continues to lope with silent strides through arable fields, boxing its peers, nibbling cereal crops, leaving elongated tracks in the sand. Its top speed is alleged to reach 45mph (72kph). Leverets are born to run, literally; they weigh less than an iPhone at birth, but are open-eyed and active. The little family scatters within days, meeting up after sunset for a brief feed from the doe. They grow while the crops around them reach their own shimmering heights, and after barely a month, are weaned. Most does will not breed in their year of birth, although after that may have up to three litters a year.

It might seem that we should be neck-deep in hares. They are a farmland species, and over two-thirds of Britain is agricultural. Yet, like the animal itself, agriculture twists and turns, and its ever decreasing ability to carry nature is a matter of profound concern. Hares, so fast and stern, now flutter as a windsock pointing to the generally troubled direction of farmland wildlife.

Their distribution in Britain tells the story. Hares have acquired a south-eastern slant in these isles– the intensive sheep grazing of the southwest excludes them. Cattle grazing creates better hare habitat than sheep pasture, but arable fields remain a critical support system, especially where hare-friendly measures, such as patches of undisturbed cover, are mixed in. Like so many species, hares benefit most from a mixed agricultural landscape rather than one devoted to a specific crop.

There are other difficulties; rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus has been recorded in hares, and more commonly, poaching haunts the species. Hare coursing is a terrible business on all levels. Apart from the cruelty to hares, it causes distress to rural communities and is often linked with wider rural crime. The hare – always listening, always watching – is sadly wise to maintain what one Victorian writer called a “passion of fear”, but it is time to give it something new: a land where it can relax, at least from overt fear of us.

Adele Brand is a mammal ecologist and writer.

She is the author of The Hidden World of the Fox (William Collins, £12.99).

MEET THE PATRON SAINT OF HARES

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the hare symbol is translated as meaning ‘to exist’. Yet it is a sad irony that many folk stories about hares reflect on death, mostly at human hands. However, heroines such as the 7th century Irishwoman Melangell sometimes step into the fray. Moving to the Berwyn Mountains in Wales and living as a hermitess, she was found by a hare fleeing a huntsman, and let it take refuge in her cloak.

The prince pursuing the animal was shaken by Melangell’s piety. He spared the hare and gave her the valley as her own. She became an Abbotess, and today the small church at Pennant Melangell holds her shrine. Melangell is now considered the patron saint of hares and her pendent shows one huddled by her side.

Hear our Plodcast on Melangell available on all good podcast providers (episode no. 46).

FLEETING GLIMPSES: FINDING HARES

Elmley Marshes NNR, Isle of Sheppey, Kent

Under Sheppey’s huge skies and just 40 miles from London, hares share over 1,200 hectares with raptors, water voles and waders.

Havergate Island RSPB , Suffolk

An island of hares and birds in the River Ore, reached by pre-booked boat from Orford Quay.

Trumpington Meadows Nature Reserve, Cambridgeshire

Not far from Cambridge, this reserve supports hares, wildflower meadows and farmland birds.

Frampton Marsh RSPB, Lincolnshire

Hares and a dazzling variety of waders and wildfowl live on The Wash’s coastline.

Cley and Salthouse Marshes Reserve, Norfolk

Famous for spectacular birdlife, this reserve on Norfolk’s lovely northern coast hosts a good population of hares.

Greylake RSPB Reserve, Somerset Levels

Look out for hares and other notable species in the wet, rushy meadows of the Somerset Levels.