Life lines

Healthy hedgerows teem with wildlife – and absorb greenhouse gases that cause climate change. Anna Turns celebrates these unsung wonders of the countryside and learns how to keep them flourishing

“Like green veins, hedgerows can act as corridors teeming with native wildlife”

Tom Hynes shoulders his toolbag and sets off from his Devon farmhouse. On the winding country lane, he pauses and points out a tiny plant growing in the hedgerow bank. Dog’s mercury, at first glance, seems quite unremarkable, until Tom explains that these plants favour well-established woods and are a subtle sign that the hedgerow contains remnants of ancient forest dating back more than 400 years.

Yet more treasures lie within this landscape near Winkleigh, north of Dartmoor. Through the wooden five-bar gate, Tom steps into a narrow acre of pasture, marked out by hedgerows that have grown here since the 12th century. “This is a seriously old hedge – it’s a culturally important connection to our past,” explains Tom.

Dressed in sturdy welly boots and old work clothes, Tom is here to carry out annual maintenance before these hedgerows of willow, hazel, field maple and blackthorn burst into leaf in spring. He last laid this section 30 years ago; each winter he restores a different hedgerow on his 20-hectare farm. For Tom, hedges are more than artefacts. He firmly believes that the highly skilled craft of hedgelaying holds the key to protecting biodiversity, capturing carbon and adapting to the climate crisis. He would love to see more hedgerows maintained in this traditional way. In fact, he says, the planet depends on it.

WHY SAVE HEDGEROWS?

Like green veins that run throughout the British countryside, hedgerows can act as corridors teeming with native wildlife. In a study made in 2011–2013, the Devon Hedge Group’s Rob Wolton identified an astonishing 2,070 species, mainly insects, in one 85-metre stretch of hedge at a nearby Hatherleigh farm. Small woodland birds and dormice nest among the nooks and crannies, and badgers, foxes and rabbits navigate through these sheltered highways to reach nearby woodlands. Bats feed on the insects living among these linear nature reserves, barn owls hunt along the high banks for small mammals and the berries and fruit growing on the shrubs provide food for other creatures throughout the seasons.

Tom unpacks his tools from his bag and lays them out on the damp ground. There’s a triangular bow saw, an axe, a traditional billhook used for cutting and a huge mallet made of solid elm, known as a beetle. He begins by neatly cutting into the smaller willow stems with his axe, using a swift, easy rhythm.

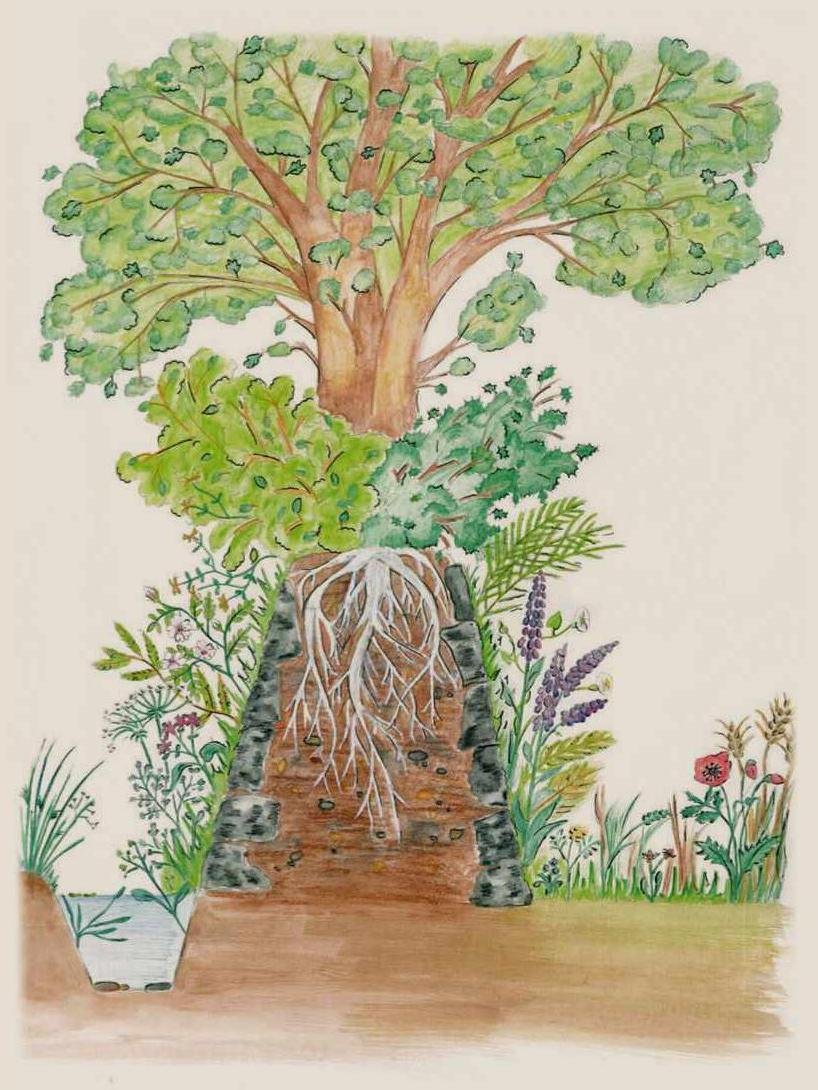

ANATOMY OF A DEVON HEDGE

Nationally, hedges vary depending on the landscape and purpose. Devon hedges, used mainly to contain flocks of sheep, are distinctive, with a bank that is either stone-faced or turf-faced sloping up from the ground and sometimes a ditch along the bottom. A diverse mix of shrubs and trees grow on top of these earthy banks, from hazel, ash and oak to blackthorn, willow and even apples, with a flower-rich margin at the base. The top bank of a Devon hedge can be up to three metres wide with space in between the hedges along either side. It’s along these structurally complex three-dimensional highways full of intertwined branches and regrowth that so much native wildlife shelters, feeds and travels.

Neglected hedgerows develop gaps – making them an unsuitable habitat for many animals that need the cover and protection of a dense hedge to avoid predators. Tom explains: “Hedges are a fantastic way of connecting wildlife across those spaces, so joining up that network is really important.”

There’s a spill-over effect, too, with bees, butterflies and other bugs pollinating adjacent crops as well as the bluebells, primroses, foxgloves and shrubs within the hedge.

“Farmers should be really proud of wildlifefriendly hedges and we, the public, should show our appreciation for their efforts in looking after these wildlife habitats,” he insists.

Well maintained hedgerows also provide some amazing ‘ecosystem services’ that benefit humans in unexpected ways. For example, they naturally slow the flow of water down slopes, reducing lowland flooding. For farmers, they help maintain soil health and reduce erosion. And for the planet, they have the potential to absorb millions of tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere, helping to slow climate change (see box below).

Here in Devon, the lanes and fields are lined with an incredible 33,000 miles (53,000km) of hedges. “In terms of wildlife and history, we’re definitely the best place in the country for hedges,” says Tom, proudly.

AN UNCERTAIN FATE

Tom is a founding member of the Devon Hedge Group, set up 28 years ago to raise awareness of the significance of this farmland habitat. The group was formed at a time when hedgerows were under threat, as many farmers dug them up or neglected them. More than half of the UK’s hedgerows have been lost since the Second World War. In 1997, legislation was introduced to forbid the removal of countryside hedges without planning permission.

The good news is that many hedges can recover from neglect. Regular hedge-laying is the best form of rejuvenation. From September to late April, stems can be partially cut near the base, then folded down to horizontal positions. From these stems, vertical shoots sprout in spring, winding upwards to thicken the hedge. Without the shade of dense woodland habitats, a huge mix of shrubs, wildflowers and wildlife can thrive.

“We want wild and messy hedgerows, nothing too manicured,” explains Tom. “That’s particularly important within an intensively farmed landscape, where modern rye grass fields are a monoculture that’s of no value to wildlife,” he adds.

DEVON’S DISTINCT STYLE

Styles of hedge-laying vary from region to region and Devon hedges look distinct. “We’ve got this unusual combination of the bank at the bottom, covered in stone or turf, with planting on top, so hedges looking like ours are fairly unique,” explains Tom.

He points out that Devon has not lost as many hedges as other regions because it remains a pastoral landscape, but in the east, where it’s more arable, fields are now much bigger. Some farmers worry that wider hedges and taller hedge trees cast shade on to crops or might get in the way of tractors. But hedges may benefit cattle. Dairy cows that get a chance to cool off during hot weather in the shade cast by trees in hedgerows produce more milk, according to Tom.

The Devon Hedge Group and other conservationists are calling for financial schemes that ensure hedge-laying becomes a regular part of farm management. “If we allow sympathetic management of our hedges so that they lock up carbon, and let them grow upwards not outwards, they won’t impact agricultural activity,” says Tom.

Hedges cost money to maintain. Tom wants Defra (the Department of Food and Rural Affairs) to incentivise farmers to grow more hedges and encourage people to learn to lay them: “Hedges are one of the easy options for tackling climate change without us all starving. We need more support for farmers to do the right thing.”

Currently, most hedges get cut by flails – a machine fitted to a tractor. Tom explains that flails aren’t all bad – they’re quick and easy to use, especially for roadside hedges, while efforts can be rotated, too, so just one tenth of a farm’s hedges could be laid once every 10 years. “[Flails] are an economic method of cutting hedges and I’d be happy to see most farms perhaps flailing half their hedges and laying the other half on rotation.”

Hedge management is certainly a compromise. Tom wonders whether farmers might enjoy planting more fruit trees in hedges so they’re more obviously productive: “That’s more like farming,” he adds. “Where they’re not intensively managed, hedges are such an important part of the countryside, and diversity is the secret.”

“As a hedgelayer, my job is to make it look neat and tidy as well as make it stockproof,” adds Tom, as he tidies up his newest section of hedge, cutting off stray branches and checking the trunks stay firmly in place. “It’s a sociable way to keep fit, get outdoors, and above all, it’s creative and constructive.”

HOW TO RESTORE A HEDGE

1 Cut through at the base of the ‘steeper’ or stem so it’s thick enough to stay alive, yet thin enough to bend without breaking. Once it feels ready to ‘give’ and release, gently bring the trunk down towards the centre of the hedge with any messy brush on the inside edge. If you’re right-handed, lay to the left; if you’re left-handed, lay to the right.

2 Using a bowsaw, cut off the remaining ‘heel’ that remains sticking up once wood has split. Once cut at an angle downwards to keep water away from the open cut so it won’t rot, the stem shows white wood, which is where regrowth comes from.

3 Offcuts of hazel branches are cut into Y-shaped ‘crooks’ that hold steepers down on to the bank. The main section of the crook is about 90cm long, with a short arm about 20cm long. Sharpen the thick end using a sharp billhook so it looks like a pointy pencil.

4 Each crook needs to be knocked into place and driven in to give the Devon hedge its structure. With the short section of the crook on top, use the beetle mallet to knock it in and secure the hedge.

5 Following destruction by animals, rain or tree fall, any gaps must be filled so the bank stays level with the steepers. Casting up involves tidying up the bank and replacing soil on the top of the bank.

Anna Turns is author of the book Go Toxic Free and an environmental journalist who specialises in climate, pollution, marine issues and our connection with nature.

HOW HEDGES FIGHT CLIMATE CHANGE

According to Defra, England’s hedges already store nine million tonnes of carbon. Hedgerows reduce greenhouse gas emissions by absorbing atmospheric carbon during photosynthesis, and storing it both above ground – in the hedgerow itself, dead wood and leaf litter – and below ground, in dense woody root systems and soil. A hedge’s ability to store carbon varies depending on how it is managed, plus the density, type, height and age of any bigger hedgerow trees within it.

Now, the Climate Change Committee recommends extending the national network of hedgerows by 40% by 2050 – that includes planting and restoring more hedges, as well as allowing them to grow wider and taller, with potential to store an estimated additional 1.9 million tonnes of carbon.

A new pilot project called the Hedgerow Carbon Code, which is run at a demonstration farm in Leicestershire by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, aims to quantify the carbon capture potential of hedgerows, develop a standard for best practice in terms of hedgerow management and generate independently verified hedgerow carbon credits to incentivise land owners to plant and manage hedges.

FIND OUT MORE

Devon Hedge Group was founded in 1994 to raise awareness of the importance of Devon’s hedgerow heritage and to help conserve these diverse habitats. devonhedges.org

The National Hedgelaying Society runs training sessions and competitions, plus the website has a useful ‘find a hedgelayer’ search tool. hedgelaying.org.uk

Hedge Link helps you find hedgemanagement contractors, download school resources about hedges, or for National Hedgerow Week. hedgelink.org.uk

Devon Rural Skills Trust runs hedgelaying courses nationwide. drst.org.uk

The Healthy Hedgerows App for farmers and land managers is free to download and a great source of help and advice. apps.apple.com/gb/app/healthyhedgerows/id1566113735

Useful books include Hedges and Hedgelaying: A Guide to Planting, Management and Conservation by Murray Maclean, A Natural History of the Hedgerow by John Wright, and Europe’s Field Boundaries by Georg Muller.

COUNTRYFILE CELEBRATES THE ANCIENT ART OF HEDGE-LAYING

Watch Britain’s best hedge-layers compete on Countryfile

In a quiet corner of Oxfordshire, just outside the English market town of Wallingford, battle commences. In a fierce competition, 100 hedge-layers from all over the country go chainsaw to chainsaw to see who will be crowned the 2022 National Hedgelaying Champion. In front of 1,000 spectators, and with regional styles to primp to perfection, who has what it takes to cut the perfect hedge?

Throughout this episode, John Craven whizzes to and fro among the competitors in his special ATV with a particular focus on the defending supreme champion; the hotly tipped pretender to the crown; the woman going for glory; and the youngest competitor. He also hops off to have a go at a Midland bullock (a particular regional style of hedgelaying), and meets with judge Robin Dale to check in on the rules.

John also discovers the crucial role hedgerows play in our countryside, as outlined in this article. There’s now a push to grow more hedges as they become recognised for the countryside champions they truly are. And they’re a particular favourite of our new King.

Apart from bragging rights and prizes, the National Hedgelaying Competition is a showcase of an important rural tradition. Delving into the Countryfile archives, John celebrates other examples of our rural craftsmanship and heritage. Catch the 2 January 2023 episode on iPlayer: bbc.co.uk/iplayer