Crake expectations

How could a farmland bird with an extraordinary call, which was once as familiar as the blackbird, have been driven from all but the outer fringes of the British Isles? James Fair investigates the case of the vanishing corncrake

CORNCRAKE FACT FILE

• DIET: A wide range of invertebrates, including many different types of insects, spiders, slugs and worms.

• BREEDING SEASON: They arrive back in Britain in mid-April, producing their first brood of chicks by late May to mid-June. Females will then have a second brood, and even – if time allows – a third.

• EGGS: Females typically lay between six and 10 eggs.

• FLEDGING: Incubation takes up to 19 days. Chicks are looked after for 14 days after hatching and fully fledge after 34–38 days.

• LIFESPAN: They are short-lived birds – most will only make it back to Britain for one breeding season. Some calling males have been recorded for three years.

If you were asked to compile a list of birds celebrated in British culture, what would you say? Nightingale, skylark and robin perhaps? Owl or swan, possibly? My guess is that you wouldn’t think of the corncrake, but it’s there, like an occasional faint streak in a stick of rock.

The 19th-century English poet John Clare eulogised the strange and ubiquitous call of the corncrake in The Landrail, while there is a more lascivious Scottish folk song about the meeting of two young lovers on the banks of the River Doon in Ayr, where “the echo mocks the corncrakes among the whinny knowes”. Stanley Baldwin, pillar of the establishment and Prime Minister on three occasions in the 1920s and 30s, described “the corncrake on a dewey morning” as one of the sounds of England, along with “the tinkle of hammer on anvil in the country smithy and the scythe against the whetstone”.

So, in the early 20th century, corncrakes were virtually as common in the countryside as blackbirds are today. However, by the 1980s and 90s – just 60 years later – they had disappeared, “among the most spectacular changes in range of any British bird species”, according to the UK’s foremost corncrake expert, Rhys Green, emeritus professor of conservation science at the University of Cambridge.

But let’s start at the beginning: what are corncrakes and what’s special about them? Why did they disappear and are we doing anything to bring them back?

“Corncrakes are renowned for their call, usually described as a rasping ‘crex crex'”

SECRETIVE AND ELUSIVE

Corncrakes are small, slightly dumpy birds, the size of a song thrush. They are part of the rail family, which includes coots and moorhens, and they come to Britain from Africa to breed, and for this they require pastures with tall vegetation in which to hide and feed. They are unremarkable to look at, though I say that with slight misgiving because I have only ever caught the backside of one retreating into cover at dusk. They are mainly renowned for their call, usually described as a rasping sound, ‘crex crex’, from where it gets its Latin name Crex crex. Personally, I find it more helpful to imagine someone playing a washboard.

The machair grasslands of the Inner Hebridean island of Tiree are the corncrake’s stronghold, and you have got a high chance of hearing one there between May and August, especially if you catch up with RSPB conservation officer John Bowler. To be honest, familiarise yourself with the song and you won’t need him. Nevertheless, it is John who introduces me to the mysterious world of the corncrake – what we know of it, anyway. They are ground-nesting birds, but unlike most waders, they do it in total secrecy. It’s only really through the declamations of the crexing males that we know they are around at all, and even their arrival (April) and departure (usually in September) is largely unseen.

“We do know they arrive and leave by night,” John says. “A colleague was counting seabirds one night, and they came towards him, flying like bricks. He wondered what these fat little birds were, then they dropped down on the headland and he could see they were corncrakes. That’s the only time I’ve heard of people seeing them flying in from migration.”

They are masters of staying out of sight. During a week on Tiree at the height of the breeding season, I heard the call every day, but saw not a twitch. If I’d known, I would have followed the advice of Rhys Green. “Go to a place where there are males singing at night,” he tells me. “Then stand and watch during the day by a piece of suitable cover, such as yellow irises. The males fight each other, and when they do, they flutter up into the air, scrabbling at each other. The have got very sharp claws, and they are fighting over a female.”

MACHAIR, A RARE GRASSLAND HABITAT

Machair is usually described as grassland growing on lime-rich shell sand and it is unique to north-west Scotland and Ireland. Some experts say it’s really defined by the traditional rotational farming (or crofting) system in these areas, that includes both pasture for livestock and growing of crops, such as barley.

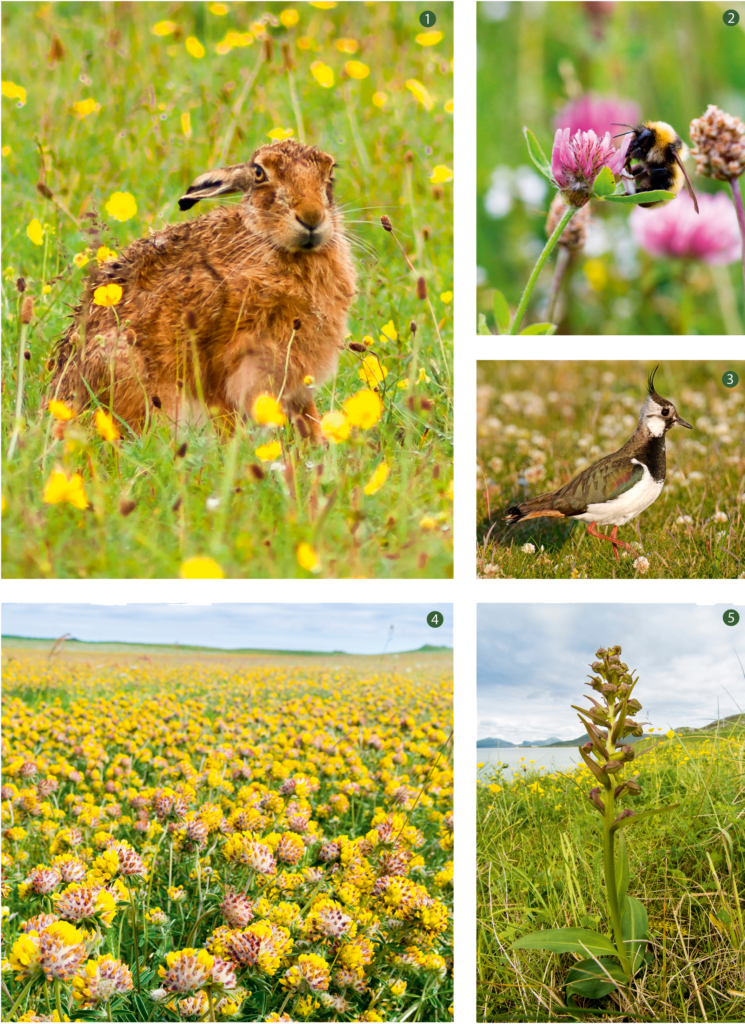

Species found on machair:

1 On Tiree, brown hares graze on the flower-rich grassland.

2 Invertebrates, including great yellow bumblebees (pictured), are attracted to the nectar-rich grasslands of the machair.

3 Many breeding waders nest on machair. Lapwings (pictured) particularly love it, but redshanks, oystercatchers and snipe are all abundant.

4 Machair is typified by high plant diversity. Earlier flowering species include yellow primroses, meadow buttercups and, later, bird’s-foot trefoil and kidney vetch.

5 Machair can be rich in orchids, including early marsh, Hebridean spotted and frog orchids (pictured).

UNCOVERING THE MYSTERY

Until Green started radio-tagging corncrakes, we knew next to nothing about them. Now we understand how British corncrakes migrate to the Congo Basin via West Africa (unlike many continental corncrakes, which overwinter further to the south and east) and also how they behave when they are here, but it’s taken months of fieldwork and a lot of ingenuity to discover this much.

Green describes how he used to tag the females and then try to find their nests for his research. By triangulating the signals from the tags, he would work out exactly where they were and he realised that, for 10 minutes every hour or so, they leave the nest to feed. Green used that small window to move in to inspect it.

“It’s unbelievably difficult to find them,” he says in obvious admiration. “They are dug down into the ground and they choose the thickest pieces of vegetation.” During one study, it took him three separate attempts to locate the nest. “I hadn’t got the place wrong, I knew where it was within one metre, but I still couldn’t find it,” he says.

To understand what has caused their precipitous decline, we must go back to a research paper written in 1944 by an ornithologist called Tony Norris. Norris showed, through correspondence with people throughout Britain (“mainly vicars”, says Green), that corncrakes started disappearing from the south-east of Britain in the 1880s and 90s and that it coincided almost perfectly with the introduction of mechanised mowing machines. Norris worked out that not only were the mowing machines killing chicks as they cut the grass for hay, farmers were using them earlier in the year, depriving corncrakes of the time they needed to fledge their chicks or have second broods.

ROAD TO RECOVERY?

Slowly, but surely, the bird disappeared, until they were only left in those parts of the country where farmers had not advanced the grasscutting dates as much as elsewhere. This was particularly true in the machair grasslands of islands such as Tiree and much of the Outer Hebrides, because farmers allow it to grow long for hay or silage, and it provides perfect cover for corncrakes. But still, until the implementation of a subsidy system in the 1990s, corncrakes continued to decline, even in the machairs. Then, farmers were paid to hold off cutting their grass, thus giving the females more time to raise their chicks and even have a second brood.

This isn’t working perfectly, Green warns, because the Scottish Government has reduced the funding. He hopes the data he, John Bowler and other conservationists have collected over the years is sufficient proof that you can protect corncrakes if you do the right thing – and that subsidies will increase again.

It might be a small, unremarkable bird that is rarely seen, but many writers over the centuries have heard its strange rasping call and it has filled them with a sense of wonder. What or who is this mysterious bird, they all seem to be saying; what is it doing here? Today, you must travel far to share that experience, but in the flower-filled machair of Tiree, Coll or the Outer Hebrides, you can still hear the corncrake call and travel back in time to when – in the words of John Clare – it was “but a summer noise among the meadow hay”.

Listen!

James Fair heads into the wilds of Tiree in search of the corncrake in episode 172 of the BBC Countryfile Magazine Plodcast.

James Fair is a journalist with a passion for wildlife and the environment.

He specialises in investigating political, controversial issues such as badger culling and the links between grouse shooting and persecution of birds of prey.

WHERE TO SEE CORNCRAKES

TIREE, INNER HEBRIDES

This is the corncrake’s British stronghold, with around 300 calling males found throughout the island. The pastures between Balemartine and Balephuil in the south are recommended.

COLL, INNER HEBRIDES

Listen for the bird at Coll RSPB Nature Reserve, which is towards the south-west of the island.

NORTH UIST, OUTER HEBRIDES

Balranald RSPB Nature Reserve, on the west coast, is managed using traditional crofting techniques, and the small fields around the visitor centre attract corncrakes.

ISLE OF SKYE

The RSPB advises that areas around Trotternish and Waternish are best for hearing corncrakes, though the population on the island is still quite fragile.

WELNEY WWT, NORFOLK

A captive-breeding and reintroduction programme managed by Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust and Pensthorpe Conservation Trust is having some success. At least six males were recorded at Welney in 2022.