Slow worm wonder

We should cherish the little legless lizard in our gardens, as much for their extraordinary lives as for the help they offer in removing pests, says Kevin Parr

The slow worm is curiously named. While it might not be the swiftest of movers, Anguis fragilis is no slouch, and no more a ‘worm’ than it is a snake, for which it is often mistaken. Instead, it is a species of lizard that has evolved without legs.

A fondness for burrowing into loose soil and nosing through dense cover or long grasses has made the use of legs redundant, but the presence of bony plates called osteoderms beneath the scales hinders their ability to slither with great speed or ease. Instead, they rely on camouflage or, more usually, the use of cover. Slow worms are cold-blooded but rarely bask in direct sunlight, preferring to hide beneath logs or rocks or within rotting vegetation where they take warmth from their surroundings.

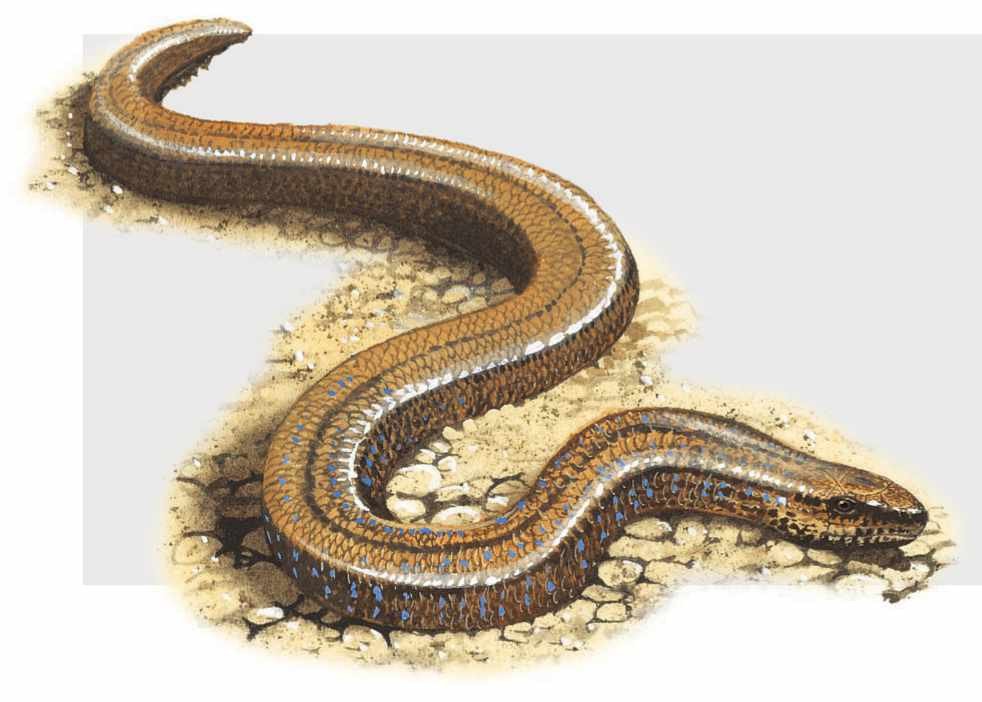

Despite their rather secretive existence, slow worms are probably the most frequently encountered British reptile. They are often found in gardens, particularly by compost heaps or leaf piles, and a tendency to stay still if discovered enables us to get a closeup view. Females are normally darker, with dark stripes along the sides, whereas the paler males develop blue spots that are vivid in spring when they are looking to breed. Both sexes grow to a length of around 50cm and the scales are smooth and dry to the touch.

“They can taste airborne chemicals to identify predators, prey and potential mates”

Whereas a snake’s eye is fixed open, with the covering a part of the skin, a slow worm, being a lizard, has eyelids and is able to blink. The eyes themselves are small, a likely reason for the alternative name of ‘blind worm’, and while they function perfectly well, the slow worm is also reliant upon its dark, notched tongue as a sensory organ. It can ‘taste’ airborne chemicals to identify the presence of predators, prey and potential mates.

SPRING FEVER

The hormonal stirrings of spring can spark less docile behaviour than might usually be associated with the slow worm. Males, wearing their lapis lazuli blue spots, will show increased aggression to one another as they compete for a mate, while the mating process itself may appear excessively violent. During a process that may last several hours, the male will grab the female’s head or neck in its mouth as the two copulate – abehaviour familiar in other lizard species. The female may subsequently carry the scars of conception as she carries the developing embryos.

Slow worms are ovoviviparous, which means that they hatch from eggs while still inside the body. This method is advantageous in a cooler climate as the female is able to better regulate the temperature of the young as they develop, whereas egglaying reptiles such as grass snakes and sand lizards are limited in their British range by the climate. A female slow worm may carry up to 12 young that are born in late summer and emerge inside a thin embryonic membrane which they then burst out of. A baby slow worm is an incredible thing; around 4cm long and with dark sides and glistening gold (or sometimes silver) backs. It has a thin dark line running along the back and a dark spot on the top of the head. Immediately independent, it will usually remain close to the place of birth to hibernate through its first winter.

The diet of a slow worm is varied and includes spiders, snails, caterpillars and worms, with a favoured prey being slugs which, once found, obviously require little effort to catch. Such a preference is a delight for gardeners and certainly a reason for slow worms to be encouraged into vegetable patches and allotments.

THREATS AND DEFENCES

Slow worms are predated by snakes, mammals such as hedgehogs and badgers, raptors such as kestrels and buzzards, and a variety of other birds, including corvids, pheasants and even blackbirds. They are often caught and killed by domestic cats. If threatened, they can release foul-smelling discharge from the anal gland as a deterrent, while they also have the ability to ‘drop’ their tail (hence the Latin ‘fragilis’ meaning fragile). This is known as autotomy, from the Greek meaning ‘self-severing’, and is used as a last-resort distraction. The tail, once dropped, continues to wriggle, drawing the attention of the predator while the slow worm flees. Autotomy occurs in many lizard species, and although it causes stress, the animal will grow a shorter and blunter replacement tail.

Such methods, coupled with a partially subterranean lifestyle, reward slow worms with striking longevity. They hibernate underground through the winter months and are slow growing, so a mature lizard may well be more than 20 years old. In captivity, they have been recorded as living for more than 50 years; an individual at Copenhagen Zoo was kept for 54 years and was of unknown age when first collected.

THE SLOW WORM FACT FILE

• The slow worm (Anguis fragilis) is a legless lizard – not a snake (or worm) – and has small eyes with lids and very little neck definition.

• The slow worm sheds its skin in parts and will leave a ‘roll’ rather than a complete skin as a snake will.

• A slow worm rarely basks in direct sunlight, and is more often found beneath logs, bark, metal sheets or buried in vegetation.

• Males are pale brown/grey with blue spots in spring. Females have dark brown sides and sometimes a thin, dark line along the back.

• The tongue is dark and shorter than that of a snake with a notch at the end rather than a deep fork.

Although the potential for long life may seem a benefit to any species, it can also create a false impression of population stability. If recruitment is poor, then a species might not be known to be struggling until a point where time catches up with the older individuals and numbers crash. Slow worms thrive in scrubland and areas with dense cover, habitats that are increasingly scarce. But their ability to live alongside humankind in gardens and suburbia might prove vital in the future. The relationship between people and slow worms has not always been convivial, though. Their snakelike appearance led to historical persecution, a fact reflected in literary portrayal. The 17th-century poet Robert Herrick referenced a ‘slowworme bite’ in The Night Piece, to Julia, while William Shakespeare alluded to the slow worm’s venomous character several times, with the witches in MacBeth using ‘blind-worm sting’ in their potion.

A slow worm is a placid creature though, and of no threat to humans or pets. Instead, with a quiet approach, encounters can be treasured: let’s slow down for the slow worm.

SNAKE OR SLOW WORM?

Slow worms are easily distinguished from our snake species

WELCOME THE SLOW WORM TO YOUR GARDEN

Gardens can provide excellent slow worm habitat and very little work is required to encourage them. They love to hide beneath wood piles or discarded metal sheeting, so rather than tidy everything away, leave a few scraps where they lie. Ensure wood piles are tucked away from the threat of falling feet and, if they are lifted, replace them carefully so that nothing might get trapped underneath.

Slow worms will often bury themselves in compost piles, so be watchful whenever turning or removing compost. Placing a square of old carpet or rubber car mat on top of the pile will offer slow worms a place to shelter and let you know if any are about.

Care should be taken when grass cutting as slow worms will not always be quick enough to evade the blades of a mower. Scan an area before beginning a cut and try to leave lawn edges or specific areas long. Slow worms enjoy the safety of deep, dense grass.

Slugs and snails make up a large proportion of a slow worm’s diet, so avoid the use of slug pellets or chemical fertilisers and insecticides. By attracting greater invertebrate diversity, you will provide food for slow worms and other animals such as hedgehogs.

Kevin Parr is an angler, nature writer and naturalist with a particular passion for reptiles. His new book, The Quiet Moon: Pathways to an Ancient Way of Being (Flint, £14.99) is out now.