INTERVIEW / PETER FRANKOPAN

“Climate is a factor that underpins all of human history”

Peter Frankopan talks to Rhiannon Davies about his pioneering new book exploring how humanity’s complex relationship with the natural world has altered over the millennia

PROFILE

Peter Frankopan is professor of global history at Oxford University, and Stavros Niarchos Foundation director of the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research. His bestselling Sunday Times number-one book, The Silk Roads (Bloomsbury, 2015), was followed by The New Silk Roads (Bloomsbury, 2018)

Rhiannon Davies: In The Earth Transformed you argue that the history of humanity is inextricably linked to the history of the environment. Why is that?

Peter Frankopan: Well, I’m not the first person to make that point. The Abrahamic faiths – Christianity, Judaism and Islam – all have an origin story rooted in the Garden of Eden. The point of the Garden of Eden is that if you obey God’s commandments, you have plenty. You have optimal climate conditions; you have ecologies that give you everything you need. But when you transgress and you eat from the forbidden tree, you’re punished by being kicked out of the Garden of Eden and forced to live in a dangerous world. Though other global religions don’t have exactly the same story, there are certainly similar ideas about humanity’s relationship with the natural environment, and how fundamental it is to our existence.

Your book is wide-ranging in scope, going back to the dawn of time. Let’s begin with a brief visit to prehistory, to the start of the Holocene [a geographical epoch that began almost 12,000 years ago]. Why do you believe that this was a watershed moment for humanity?

Around 50,000 years ago, long before the Holocene, our subspecies – Homo sapiens sapiens, or modern human beings – started to spread out across the continents, displacing Neanderthals and other hominins. It will be no surprise to anybody who’s studied history that the places that were colonised first were the areas that often spring to mind when we think about early human history: the Nile; Mesopotamia; the Indus Valley; and along the Yangtze and Yellow rivers in China. As those societies grew in size, they became more complex, and the challenges and opportunities that arose required new kinds of solutions. For instance, what do you do when your growing society has hunted all the large mammals around you to extinction?

Then, around 11,700 years ago, there was an uptick in global temperatures following the last ice age, marking the start of the Holocene. This was also the moment when our ancestors started to behave in slightly different ways. They were testing which technologies worked and which didn’t, and how to pass on those successes to future generations – such as the spread of metallurgy across Asia, around 6,000 years ago.

However, there’s a caveat here. In the book, I always try to be very careful to say that nothing happens solely because of climate change, though climate is always a factor that underpins everything. For instance, it goes without saying that local environmental conditions dictate what we can grow. In Britain, for instance, we’re quite good at farming wheat and cows, but we’re not very good at growing pineapples. It stands to reason that people are shaped by their ecological opportunities.

You compare the experiences of settled societies and nomadic societies in navigating environmental change. How have their responses differed over the centuries?

I carry a torch for nomadic peoples – mobile groups – partly because of the work I’ve done on the peoples of Central Asia. Typically, in written sources, from Herodotus and early thinkers right up to the present day, nomadic peoples are denigrated by all sorts of writers, who tend to be metropolitan and city-based. They often think that the way mobile groups live – because they don’t live in cities – is primitive and unsophisticated.

In fact, though, mobile groups are extremely adept at understanding their ecologies – if they don’t, their flocks die and their way of life disappears very quickly. Mobile groups have also contributed hugely to the way of life of city-dwellers: historically, nomadic people have provided sedentary groups with protein, dairy and textiles, such as leather and wool, in exchange for goods like grain.

We also tend to think that if you don’t write down histories on a page, but instead rely on oral traditions, as lots of nomadic groups do, then you’re a bit-part player. But we need to think about how to integrate the histories of non-sedentary and mobile peoples into global histories, and how to learn from indigenous populations about surviving in nature. For example, over many centuries the Bushmen of the Kalahari have become fantastic at working out which plants work best as medicinal remedies – and now pharmaceutical companies are claiming this knowledge as their own.

Coming back to the experiences of settled societies and nomadic societies, from an environmental perspective the trend towards city living does present some key problems. More than 200 years ago, only 3 per cent of the world’s population lived in cities; by the middle of the 20th century, that number had jumped to around 30 per cent. It doesn’t take much to realise that this shift has hugely increased demands for energy, food and water in those places.

It’s also difficult to build cities with sanitary conditions that don’t help spread disease. And, as we all learned during the Covid-19 pandemic, the best way to protect yourself from disease is to keep away from each other. If you live in cities, that’s really quite tricky.

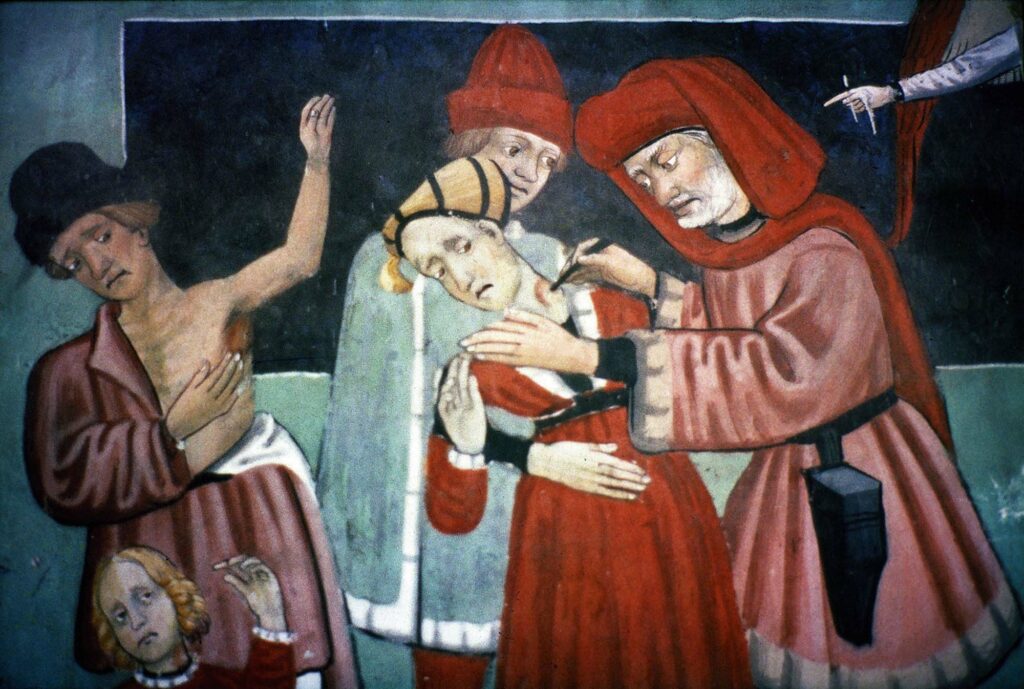

How far back can we trace a link between disease and climate?

Pathogens need a perfect storm of different factors for them to spread. Often they’re highly influenced by changes in climate, particularly changes in temperature. But climate on its own is not enough: some diseases also need vectors to distribute pathogens, such as rats or birds. Lastly, you ideally need lots of people living close together to easily spread the infection.

Let’s take plague. The most famous outbreak was, of course, the Black Death in the mid-14th century, but the disease has reared its head again and again throughout history. We find it, for example, around 6,000 years ago in the Trypillia culture of what’s now Ukraine and southern Russia, where there was a sudden population collapse, probably linked to the spread of plague.

This illustrates a wider point about globalisation. When people connect with each other and trade with each other, they take things with them that aren’t just good news or cheap goods. These networks also have a real downside, and they can in fact prove deadly.

One of the main themes that I took away from your book was the prevalence of attempts to control both other people and nature. How has that played out throughout history?

Even going back tens of thousands of years, humans have generally wanted to live in places that look nice, that are hospitable and that aren’t infested with poisonous animals or dangerous plants. We want running water and nice sunsets. But that’s meant that we have intervened in the natural environment, often very aggressively, to shape it into the ideals that suit us – and we’ve often pushed a bit too far.

One of the key issues connected to this, which we see across many civilisations, is around the availability of labour, and questions of coercing labour – be it enslavement or indenture. This has been with us for as long as we have written records, and earlier than that, too. Inequality is an important part of our human story. And it’s an important part of ecological exploitation, because if you want to grow things or if you want to rear animals, you need people to do it for you.

What were the ecological consequences of the colonisation of the New World?

The transformation of the Americas ecologically, from plant life to pathogens to humans to animals, was beyond seismic – it was epochal. Think about the human population. It’s well known that the arrival in the New World of diseases carried by Europeans – who themselves had a degree of immunity – was a disaster for indigenous peoples across the Americas. This, coupled with numerous acts of violence, devastated indigenous populations.

In addition, pigs, cows and horses – none of which are indigenous to the Americas – were introduced and became part of ecosystems. Today, Brazil is the biggest global exporter of beef. The cattle are reared – at the expense of habitats such as rain forest, which is cut down for pasture – to create beef patties that typically don’t get consumed in South America but are shipped around the globe. So the remodelling of nature, of ecologies, of working out how to do things as cheaply as we can – because that’s really what it comes down to – has long-term consequences that we should have been thinking about for a lot longer, instead of how to exploit nature and other human beings.

But consequences weren’t just limited to the Americas. We call it the Columbian Exchange, this post-Columbus moment when things were travelling across the Atlantic in both directions. Some of the things that are hugely significant in our modern world, like potatoes, hail from the Americas and have shaped global history. Economists are studying how the introduction of the potato helped reduce conflict in Europe and Asia. Potatoes are cheap and easier to grow in difficult climates than many other crops, so by cultivating them people could more easily feed themselves, meaning there was less to fight about. This led to a measurable drop in levels of confrontation.

But potatoes were far from the only crop involved in the exchange. There was also sugar and cotton, which were grown by enslaved people in the New World. Again, the question of labour becomes a pre-eminent one. Here in Europe, we have a very dark history of transporting people against their will across the Atlantic, to work in disgusting conditions to produce crops at the cheapest possible price.

How long have people understood that the actions of humanity affect the environment?

For as long as we have written sources. These questions are hugely significant in the Vedic texts of ancient India, for instance, and the early rise of Buddhism. As to why people have engaged with these ideas for so long, I think it’s partly down to the common experience of floods and droughts and lightning strikes, which troubled our ancestors and led them to want to work out why they happened. Many global religions also have means of praying for better weather – through offerings in Mesoamerican societies, for example, or sacrifices in Mesopotamia.

Focusing specifically on contemporary concerns about global warming, we tend to think about the climate crisis today as being something that’s caught up with us in the past five or 10 years. However, people have been deeply concerned about carbon dioxide emissions in the atmosphere for 200 years. The question is: why has no one done anything about it?

“We tend to think about the climate crisis as a modern worry, but people have been deeply concerned about carbon dioxide emissions for the past 200 years”

Climate change is a huge concern in 2023, but you also point to natural disasters – such as volcanic eruptions – as being particularly threatening. Why have they been so significant through history?

Volcanoes have played a major role in our past. For example, there was the Santorini eruption in c1600–1500 BC. When most people think about Santorini, they probably picture this amazing island in the Aegean, and know that it had something to do with the collapse of the Minoan civilisation in Crete. But when the volcano on Santorini erupted, it also, and probably more importantly – with my apologies to anybody living in Crete at the time – may have prompted animal movements that helped spread smallpox into human populations. The disease was devastating: from 1900 to 1980, when smallpox was eradicated, it is believed to have caused more than 300 million deaths.

Surprisingly, volcanic events have also impacted the realm of romantic literature. The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 led to months of disrupted weather and produced the so-called “year without a summer” in 1816, which was a factor in Mary Shelley starting to write Frankenstein. That year, she was among a group of English writers staying on Lake Geneva, hoping they’d have a nice summer holiday with blue skies. Instead, they were subjected to lightning storms, grey skies and freezing cold, so they challenged each other to write ghost stories. Thus Frankenstein was born.

Volcanic eruptions have sparked some of the most dramatic turning points in history – indeed, even before we established ourselves as a species. One would expect that a huge future eruption will also play a big role in the future. Whether we’re a year, 100 years or 1,000 years away from it, I don’t know. But when it comes, it will turn everything upside-down.

However, in today’s nuclear world there are other pressing threats. While I’m sitting here talking to you, someone in Moscow or in Pyongyang might decide that the time has come to take matters into their own hands – and I can promise you that a nuclear war will be even more devastating than a volcanic eruption.

I grew up in the 1980s, and my generation was convinced that we would die in a nuclear catastrophe caused when the Soviet Union and US launched warheads at each other. But even a very small-scale set of nuclear events, which doesn’t involve every single missile being lit up in its silo, can have a very dramatic impact on crops, and can cascade into deaths measuring into the tens of millions. Rather than succumbing to natural courses, I think we’re more likely to be the architects of our own downfall.

What’s the biggest lesson we should learn from the past when trying to forge a better future?

I would, respectfully, probably say that my job as a historian is simply to say what’s happened, and let people take their own lessons. The reason I’m slightly guarded is that when I wrote The Silk Roads, I assumed that people would ask me all the time about the rise of Islam, or what was going on in the exchanges with the Americas. But the only things anybody ever asked were: “What’s happening with China today, and is Putin going to invade Ukraine?”

Rather than looking ahead, I think the first point for a historian is to explain how we’ve got to where we are. I’m also keen to encourage readers to think about parts of the world that have been under-examined across different periods. From these, one can learn from things such as migrations, from disease, from what societies in bloom or under stress look like.

However, if I had to suggest any lessons to learn, I suppose there are two obvious and logical points to make. Number one: we’re in a bit of trouble. Everyone will have strong views about climate and about the data available, but we should probably be thinking quite hard about mitigation, because the ship has sailed on stopping climate change – it’s now about what happens next.

My second point is that we all rise and fall together. When dislocation happens, it’s never one pillar that fails and everything else goes on as before – we’re all in it together. Within this world of global governance, we’ve seen with Russia and Ukraine – and elsewhere on the planet, too – that the question of how we co-operate still continues to vex us. Looking at climate and the 2015 Paris Agreement [an international treaty aiming to limit global warming this century to 2¼C above pre-industrial levels], not a single one of the G20 is within the parameters that they set eight years ago. Our inability to co-operate is our single biggest Achilles heel.

The Earth Transformed: An Untold History

by Peter Frankopan

(Bloomsbury, 736 pages, £30)

PODCAST

How did climate shape the Spanish flu?

Find out by listening to the full interview with Peter on our podcast, or watch the video on our website: historyextra.com