SCIENCE

Competing theories?

Patricia Fara is swept up by a novel exploration of the intertwined histories of science and religion spanning several continents and many centuries

When Samuel Johnson embarked on the daunting project of compiling an English dictionary in 1746, he aimed – as he later said – to “embalm his language, and secure it from corruption and decay”. By the time he called a halt several years later, he had been forced to acknowledge that this was an impossible task: language changes, words constantly shift, instability reigns. Or, as Humpty Dumpty informed Alice, a “word means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less”.

In his looking-glass world, Humpty Dumpty neglected to comment on one particularly slippery term: science. Its use has varied so widely that sometimes it does seem to have meant whatever its user intended. So as Jane Austen’s Mr Darcy gazed across the ballroom, an onlooker complimented him on his dancing skills by remarking: “I doubt not that you are an adept in the science yourself.”

In Magisteria, Nicholas Spencer tackles many centuries of debates over the nature of science and its complex relationships with religion. With this exceptionally thoughtful and lively book he convincingly debunks familiar stories of head-on confrontation, instead posing two questions: what (or who) is the human, and who (or what) gets to say? Fortunately, that enigmatic pronouncement, printed in bold on the press release, makes more sense when you read the book.

Magisteria is a large volume with an esoteric but imposing title that stems from evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould’s bid – now mostly forgotten – to quell the “Science Wars” of the 1990s by defining science and religion as “Non-Overlapping Magisteria”. Spencer disagrees with Gould’s model of separate spheres. The basis of his own illuminating analysis is to argue that science and religion share tortuous, messy pasts; repeatedly interacting, at times they have reinforced one another, at others opposed. Spencer imagines two rivers meandering intertwined through a historical landscape. One carries the problem of deciding who holds authority, who makes the decisions about what is right and what is wrong; the other, increasingly important after around 1600, concerns human identity and its spiritual nature. It was only when these rivers converged in the later 19th century that the unhelpful narrative of warfare was created.

Getting their hands dirty One key event occurred in 1833, when the author Samuel Taylor Coleridge berated the members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science for behaving in an unscholarly, ungentlemanly manner. Men who dug up fossils and tinkered with electrical machines did not, he sneered, deserve to call themselves natural philosophers. Thinking quickly, a Cambridge academic calmed the situation by inventing a brand-new word – scientist. It caught on very slowly: Faraday and Darwin are acclaimed as great Victorian scientists, but both rejected the label.

“The basis of Spencer’s illuminating analysis is to argue that science and religion share tortuous, messy pasts”

Despite Coleridge’s contempt, scientists had no qualms about getting their hands dirty – though they also wanted to boost their social status. Many thus set themselves in opposition to religious authorities, the traditional guardians of knowledge; naturally, the church was similarly eager to safeguard its own territory. Throughout this supposed war between science and religion, fundamentalists on both sides launched vitriolic attacks, many of them ill-informed. Like several other eminent physicists, the Nobel Prize-winner Steven Weinberg refused to acknowledge the religious dedication of Isaac Newton but recycled the facile assumption that he eliminated God from the universe. For Newton, the whole point of studying the universe was to fathom God’s intentions, whereas Wein- berg commented that “the more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless”. As a student, Newton learned that theology lay at the summit of the scholarly syllabus as the “Queen of the Sciences”; however he may have conceptualised this hierarchy, there was certainly no inevitable clash between the two domains.

Despite the subtlety of Spencer’s approach, he rather undermines his project by calling all his actors scientists, even describing Aristotle as “the greatest of ancient scientists”. This is no mere pedantic quibble: that word – so common now but relatively unfamiliar as little as 100 years ago – emerged as part of the very debates that Spencer aims to pick apart. There was no inevitability about the route from the Greeks to the future, which might have proceeded very differently. Edward Gibbon predicted that Newton would be celebrated for redating ancient dynasties, commenting that “his System of Chronology would alone be sufficient to assure him immortality”. Yet, despite Newton’s obsessive preoccupations, it would now seem strange to call him a historian or a theologian; conversely, describing him as a scientist pre-emptively excludes the commitment to theology that Spencer has set out to explore.

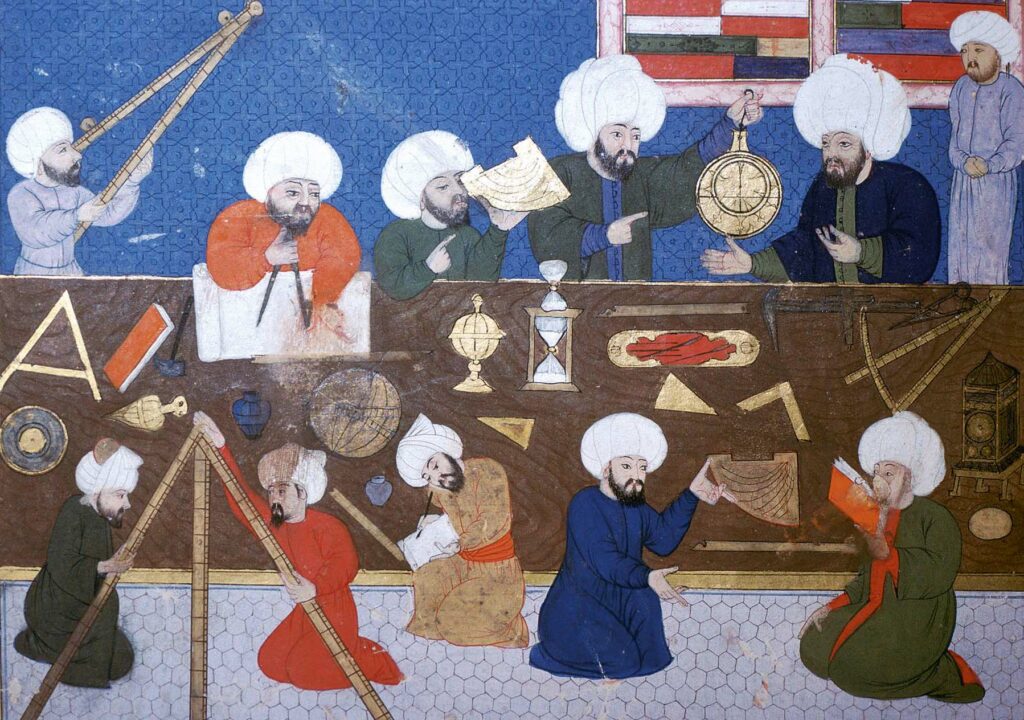

Spencer makes an impressive bid to get away from Eurocentric stories about science. Starting with the classical world, he embraces Islamic, Judaic and Christian viewpoints up to 1600. He then divides Magisteria into two further and more narrowly focused chronological sub-sections, the first continuing to the late 18th century, the second running through to current discussions of artificial intelligence, cyborgs and robots. This three-part structure ingeniously enables Spencer to paint a panoramic picture while also depicting individual episodes in greater detail. The result is a book that is gripping to read and unified by an insightful interpretative framework.

Magisteria opens with the most famous myth about scientific martyrdom in the face of religious obstinacy – the elderly man who eventually confesses his errors to a papal tribunal but stumbles away muttering: “Yet still it moves.” As Spencer demonstrates, the matter at stake was not so much Galileo Galilei’s insistence that the Earth revolves around the sun, more the Catholic church’s determination to maintain its reputation and resist encroachments on its power. A devout Christian, Galileo wittily articulated one way of thinking about the relationship between religion and science: “the intention of the Holy Spirit is to teach us how one goes to heaven, not how heaven goes.”

Patricia Fara is a historian of science and emeritus fellow at Clare College, University of Cambridge

Magisteria: The Entangled Histories of Science and Religion

by Nicholas Spencer

Oneworld, 480 pages, £25

All products were chosen independently by our editorial team. Below is an affiliate link, and we may receive a commission for purchases made. Please read our affiliates FAQ section underneath the Letters page to find out more.