HISTORIC CITIES

Prague in five places

The Czech capital’s streets are packed with history. Eleanor Janega selects five key sites that shed light on Prague’s storied past

1 Vyšehrad

A castle of grave importance

Legend has it that Prague was founded by a princess, Libuše, who met a ploughman named Přemysl; together they spawned the Přemyslid dynasty, which ruled Bohemia until the 14th century. By tradition, the site of their first castle was Vyšehrad (“Castle on the Heights”), south of the city centre, still defended by imposing ramparts. It was largely rebuilt in the 14th century by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, who substantially overhauled the city and sought to connect himself with these old legends. The site also encompasses the 11th-century Romanesque Rotunda of St Martin and a lovely old basilica.

The most fascinating element, though, is the great cemetery, home to many graves from the Romantic period: here lie composers Antonín Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana, and artist Alphonse Mucha, whose glorious Art Nouveau paintings are still used in countless adverts. It’s a who’s who of 19th-century Prague, revealing the romantic notions that such people had about nationality: they wanted to be connected to Vyšehrad, to be seen as Czech rather than Austrian, to be part of the ancient legend. There are also wonderful views out over the river and the city, providing a bird’s-eye view of the development of Prague over time.

2 Emmaus Monastery

Creating a cultural movement

This 14th-century edifice, also known as the Slavonian Monastery, is interesting not just because it’s beautiful, but also because of what it tells us about Charles IV’s ideas of Slavic Christianity. Deciding to make Prague a new religious capital, Charles had the city promoted to an archbishopric. He also welcomed members of various religious orders that didn’t previously have a presence in Prague to set up houses here. Notably, he invited a group of monks from the Dalmatian coastline, in what’s now Croatia, who practised the Slavonic rite.

In effect, Charles was making an important point about the Czech people, nurturing a Slavic form of very pure Catholicism to show off to the rest of the world. Though rebuilt and restored several times over the centuries, the monastery still boasts wonderful 14th-century frescoes that are worth a visit in themselves. But more importantly, it’s a powerful testament to the way that medieval propaganda worked, and the clever methods by which emperors moved pieces around in order to make themselves look great.

3 New Town Hall

Breaking religious boundaries – and windows

At the top of Charles Square (Karlovo náměstí), an easy stroll from Emmaus Monastery, looms a wonderful Gothic tower on a building with extraordinary stepped sides. This is the New Town Hall, site of the First Defenestration of Prague – a violent episode that set a trend repeated twice more over the following centuries. Here, in 1419, a mob led by a priest named Jan Želivský threw seven Catholic city councillors out of the window, marking the start of what was later known as the Hussite Wars, auguring what became the Protestant Reformation.

The beautiful building was constructed around 1348, when Charles IV founded the New Town, though the tower – which affords fine views – was added a century later.

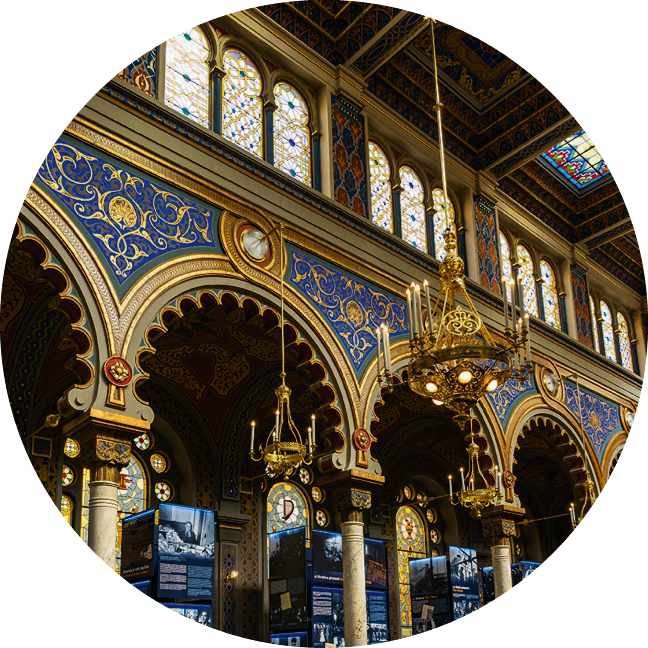

4 Jubilee Synagogue

Celebrating the beauty of Jewish Prague

Built in 1906 and designed by Wilhelm Stiassny, the building also known as the Jerusalem Synagogue is a wonderful example of Moorish Revival architecture, which specifically looked to the Ottoman empire for inspiration, blended with art nouveau decoration. The result is somewhat overwrought but absolutely gorgeous.

It has been in continual use since opening, except when it was used to store confiscated Jewish property during the Nazi occupation. Between 1941 and 1945 more than 46,000 Jews were deported from Prague, mostly to the Theresienstadt ghetto-camp from where the majority were sent to extermination camps.

The synagogue is open to the public, and – together with older sites in the Josefov district, including the Old-New Synagogue and Old Jewish Cemetery – a very important reminder of how integral the Jewish population has been to the success of Prague for at least 10 centuries.

5 National Museum

Scars of a Soviet crackdown

Scan the walls of the National Museum (Národní muzeum), at the top of Václavské náměstí (Wenceslas Square), and you can make out the traces of bullet holes from the Prague Spring of 1968, when Soviet forces brutally cracked down on attempts at political liberalisation of the hard-line communist government. It’s moving to witness the real scars left when one country is forcibly controlled by another against its will, and it’s interesting to see how cultural monuments can occupy such an important place in the psyche of a country. Czechs were hugely upset that anyone would shoot at their museum, so the bullet holes were left in the facade and a plaque installed describing the episode. When gazing at these marks, consider what it would feel like if foreign tanks rolled into your neighbourhood.

Václavské náměstí has long been an important venue for demonstrations. During the Prague Spring, students marched on the square to demand light, because there was a blackout while they were trying to study for their finals. And in 1989, dissident poet (and, later, the first president of the Czech Republic) Václav Havel addressed the crowds here after being released from prison. Whenever something major occurs, Prague residents flock to Václavské námesti.

Dr Eleanor Janega, who has Czech and Slovak roots, is a guest teacher in the Department of International History at LSE. Her new book, The Once and Future Sex, will be published by WW Norton in March 2023. She was talking to Paul Bloomfield, a travel journalist and the host of HistoryExtra’s new podcast series, History’s Greatest Cities

PODCAST

How good was King Wenceslas?

Eleanor discusses Prague on our new History’s Greatest Cities podcast series: hexpodcast.podlink.to/Cities