The Chamberlains and Cadburys

The first families of the second city

The story of modern Birmingham is dominated by two clans, whose radical views and fierce commitment to public service forged its distinctive identity. Richard Vinen traces the rise of the Chamberlains and the Cadburys

Workshop of the World. Chocolate Capital. Venice of the North. Just plain “Brum”. Birmingham, now Britain’s second-largest city, has attracted a host of nicknames but one distinctive identity, forged in large part by the actions of two families – the Chamberlains and the Cadburys. These dynasties dominated Birmingham’s industry, politics and society across the 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet, guided by faith, philanthropy and public service, they wielded enormous influence at a national and global level, too.

During the later Middle Ages and Tudor era, Birmingham had grown from a modest market town into a prosperous urban centre known for wool, leather and metalworking. At the start of the 18th century, it was home to around 15,000 people. Over the following decades, Birmingham played a leading role in the industrial revolution, with a corresponding boom in its population, which topped 73,000 by the end of the century. Among those thousands drawn in to this burgeoning Midlands powerhouse were the Chamberlains, who would go on to spawn a British prime minster, and the Cadburys, whose surname became known as a global brand.

The impact of these families is revealed vividly in the words of one young woman writing in the 1880s. Twenty-four-year-old Beatrice Potter (later known as an influential sociologist under her married name of Webb) had fallen in love. She had been bowled over by the power of her paramour’s personality, but she was shrewd enough to see that he was more than an extraordinary individual. He represented a whole milieu, one that showed little interest in the trappings of the elite and was fired by a fierce commitment to social activism. “He is supported by the powerful clan to which he belongs,” observed Potter. “They stand far above the town society in social position, wealth and culture; and yet they spend their lives, as great citizens, taking an active and leading part in the municipal, political and educational life of their town… There is one eternal refrain: Birmingham society is superior in earnestness, sincerity and natural intelligence to any society in the United Kingdom!”

The object of Potter’s affections was Joseph Chamberlain – a former industrialist and Liberal politician who, from 1873–76, had been mayor of the city where he’d made his fortune and his reputation.

Chamberlain arguably had a greater impact on the evolution of Birmingham than any other politician. He came to the city in the early 1850s at the age of 18, to make his fortune in industry; having done so (in the family’s screw-manufacturing business), he threw himself into public life. He purchased the gas companies on behalf of the council, improved the city’s water supply, was a driving force behind the construction of Birmingham’s main shopping thoroughfare, Corporation Street, and was responsible for a large number of civic buildings. In short, while mayor, Chamberlain pioneered a new level of activism in municipal government that caused an American journalist to describe Birmingham as the “best governed city in the world”. He entered parliament, first as a Liberal and then – after his opposition to home rule for Ireland caused him to break with prime minister William Gladstone in 1886 – as an ally of the Conservative party.

Though the most senior office that Joseph Chamberlain held was that of colonial secretary, he transformed British politics – partly because he developed a model of rightwing populism that continues to shape politics today. Joseph’s eldest son, Austen, served as foreign secretary in the 1920s. His younger son, Neville, became prime minister and is remembered best – or worst – for the Munich Agreement with Hitler of 1938.

Joseph Chamberlain arguably had a greater impact on Birmingham’s evolution than any other politician

The model dynasty

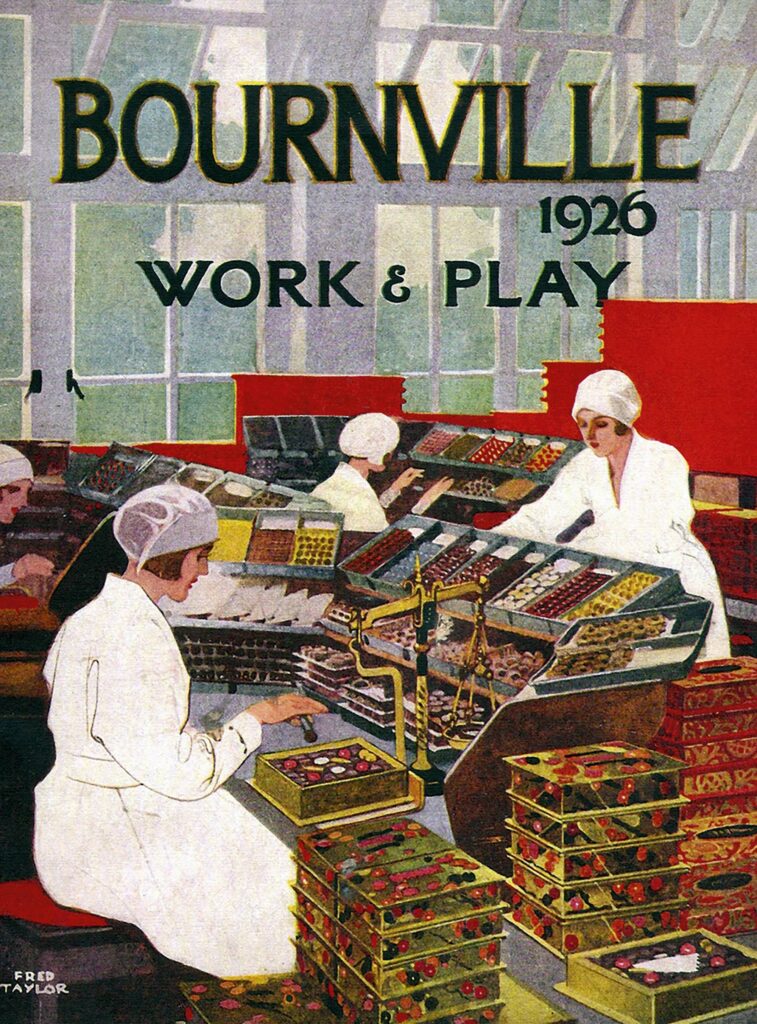

The Cadburys had been in Birmingham since the late 18th century. They were less politically active than the Chamberlains, though two served as mayor of the city. The Cadburys’ reputation sprang from their success as chocolate manufacturers. In the interwar period, the Cadburys reckoned that 90 per cent of the entire British population ate chocolate – a fact that made the family brand enormously profitable.

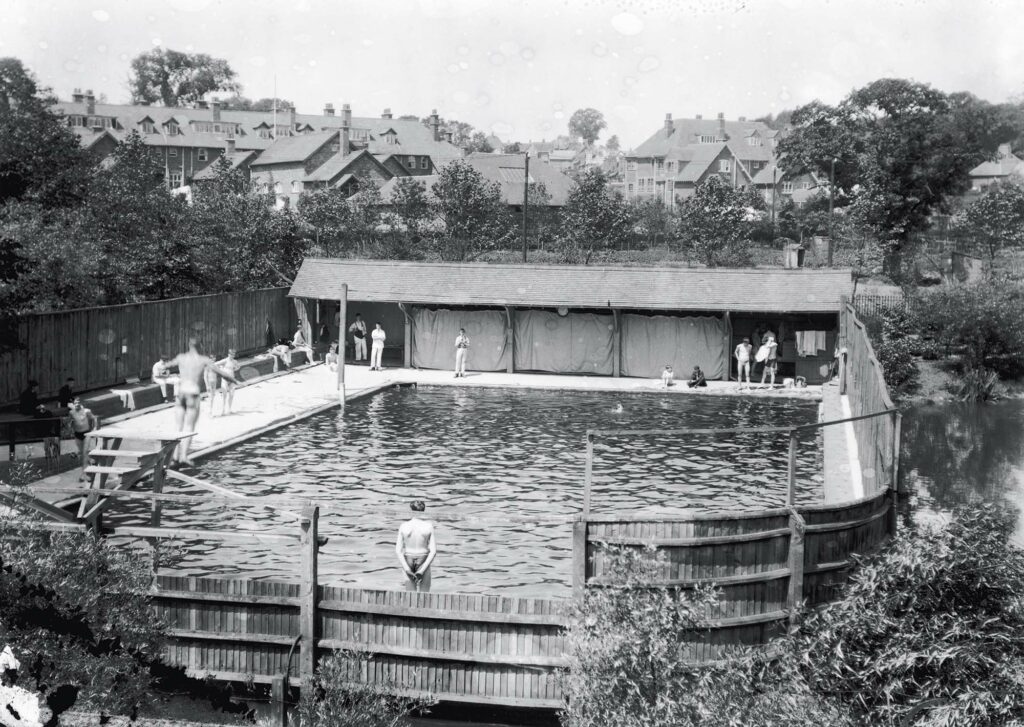

The Cadburys also became famous for philanthropy. The model village they had constructed in the south-west Birmingham suburb of Bournville was not only designed to accommodate the workers at their factory, but to offer them access to open spaces and community services. Replete with a lake, parks, a bowling green and a lido, it became a blueprint for model villages across Britain.

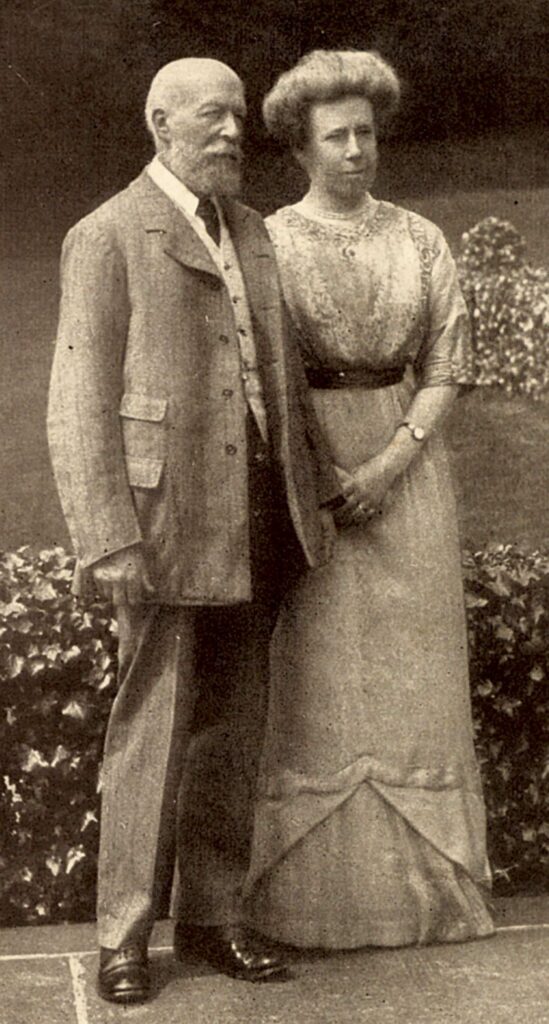

These two great Birmingham families had much in common. They were, for a time, neighbours. When Joseph Chamberlain built the house he named “Highbury” in Moseley in the south of the city, Richard Cadbury – the second son of John Cadbury, founder of the chocolate business – moved next door.

(Neville Chamberlain, already displaying the snobbery that would often mark his attitude to his native city, referred to the Cadbury house as “the cocoa palace”.)

Both families were closely associated with the suburb of Edgbaston, because it is here that they lived for much of the 19th century. Edgbaston was owned by Lord Calthorpe but, strangely, aristocratic ownership sat alongside bourgeois power: the area became the great centre for Birmingham industrialists, who found in it a place where they could enjoy semi-rural tranquillity while remaining, as one of the Cadbury family recalled, “within smelling distance” of the factory.

Birmingham had no real native aristocracy, and its dominant families – unlike industrialists in other parts of the country – felt no deference to noble families and, most importantly, showed no desire to emulate aristocratic lifestyles by purchasing country estates. When the Cadbury family acquired large swathes of land around the Lickey Hills south-west of the city centre, rather than seeking to establish themselves as country gentlemen, they simply gave it to the city of Birmingham.

The position of the Chamberlains and the Cadburys was also underpinned by religion. The former were Unitarians (Protestant dissenters who believe in the unity of God rather than the holy trinity); the latter Quakers (who hold that each human contains something of God). Both of these denominations were small but they wielded an influence that reached beyond their numbers. Their followers were often prosperous and imbued with an extraordinary intellectual and cultural self-confidence. Though the two faiths between them amounted to less than one in 20 of Birmingham’s population, they accounted for more than half of the town councillors on whom Joseph Chamberlain could depend for support.

Exclusion from the English religious establishment went hand-in-hand with distance from the establishment in a more general sense. Unitarianism had, at least in theory, been illegal before the early 19th century and, until later that century, nonconformists were effectively excluded from ancient universities and English public schools. But the institutions that counted for the British ruling class meant little to the Birmingham notables. Joseph Chamberlain allied with Conservative aristocrats when it suited him but never regarded them as his superiors. And he laughed at the idea that he might accept an aristocratic title for himself.

Radical views

Both the Cadburys and the Chamberlains took positions that were – by the standards of their time, and sometimes even by the standards of ours – extraordinarily radical. Though he eventually allied with Conservatives who regarded the defence of church and crown as the key to their politics, Joseph Chamberlain had been an open republican in the 1860s, and seems to have become an atheist after the death of his second wife, Florence, in 1875. As for the Cadburys, their sympathy for pacifists survived the climate of hysterical militarism that swept Britain in 1914.

Political radicalism, though, eventually took the two families in different directions. Despite Joseph’s earlier liberalism, by the end of the First World War, the Chamberlains were, to all intents and purposes, Conservatives. They took Birmingham with them. Between 1931 and 1945, every single one of the city’s 12 MPs was from that party.

The Cadburys did not follow Joseph Chamberlain when he broke with the Gladstonian Liberals. Cadburys and Chamberlains then maintained a wary stand-off – disagreeing with each other but avoiding direct confrontation. In 1921, William Cadbury (then lord mayor of Birmingham) told the government that his Quaker principles prevented him from helping to organise ex-soldiers to protect strike breakers. The cabinet, chaired by Austen Chamberlain in the absence of the prime minister, merely passed this duty to the mayor’s deputy.

Both the Cadburys and the Chamberlains were, by the standards of the time, incredibly radical

The politics of the Cadbury family were more discreet than those of the Chamberlains. Often, they operated a division of labour. Women of the family were active in public life while their husbands and brothers occupied themselves with the more mundane business of making money. Dame Elizabeth, the great matriarch of the family, was particularly important. In 1923, she even dared challenge the motor manufacturer and Conservative MP Herbert Austin in his own King’s Norton constituency.

As the Chamberlains moved to the right, some members of the Cadbury family drifted to the left and joined Labour. This was particularly important, because the Cadburys came to provide a refuge for leftwingers in the Chamberlainite citadel. The Cadbury factory tolerated trade unionists at a time when almost every other factory in Birmingham was looking for excuses to sack union activists. When Dame Elizabeth’s stepson George Cadbury sat as a Labour councillor in the 1920s, six of his colleagues were employees of his family company. Bournville, which accounted for less than one in 30 of Birmingham’s population, contained a quarter of its Labour councillors.

Diverging paths

The political system associated with the great Birmingham families came crashing down in 1940. The name of Chamberlain, which had counted for so much in the city’s politics, became a liability because of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s association with appeasing Hitler following the Munich Agreement. Labour, which had not won a single parliamentary seat in the city since 1929, gained most of them in 1945. The trade unions could suddenly call the shots in the full employment of the war economy.

The Chamberlain family almost evaporated. Its members moved to London and, with surprising frequency, to the political left. The two best-known descendants of Joseph Chamberlain – Harriet Harman and Lady Antonia Fraser – are both quintessentially metropolitan figures.

The legacy of power

There are two general lessons that we might draw from the stories of the Chamberlain and Cadbury families. The first relates to the frequently advanced suggestion that Britain suffered from the absence of a “bourgeois revolution” – that its middle class was weak, deferential and desperate to assimilate into the landed aristocracy. The Chamberlains and the Cadburys would have laughed at such an interpretation. Between the 1860s and the 1940s, Birmingham – more than anywhere else in Britain – illustrated the power of an autonomous middle class. It is no accident that some of the city’s grandest public buildings were modelled on those of Venice, because Birmingham really did sometimes seem like an Italian city state – a place in which a merchant class ran their own affairs with little regard for monarchy or nobility.

Another interpretation, though, might contrast the two families. The Chamberlains rose and fell quickly – the period between Joseph Chamberlain’s first election as mayor and his son Neville’s deposition as prime minister lasted less than 70 years. Joseph was a volcano of a man: aggressive, mercurial and prone to take extraordinary risks. He often talked of both commerce and politics as if he were describing a military campaign in which his opponents were to be broken. His sons were always painfully conscious that they lived in their father’s shadow. Neville compared himself to Hamlet being haunted by his father’s ghost.

The Cadbury family produced no comparable great figure. Sir Adrian Cadbury, George’s grandson, was behind a 1992 report on corporate governance that suggested that no single person should exercise too much power in a company. The overall ethos was that individual ambition should be subordinate to the interests of the family and the business.

More than any British city, Birmingham illustrated the power of an autonomous middle class

The Cadburys stayed in Birmingham for decades after the Second World War, modernising the company through flotation on the stock exchange and a succession of mergers. Yet their political influence waned. Politics and business were now becoming full-time occupations, and the Cadburys increasingly focused on the latter. Despite that, they retained a nostalgia for their family’s radical roots. Sir Adrian occasionally took time off from his duties with the Confederation of British Industry to write letters to the communist historian Eric Hobsbawm, who had taught him at university.

Eventually, Cadbury family control of the company ended when it was sold to an American buyer, though the Bournville works remain. Now that Dunlop tyres and the Longbridge car factory have both closed, it is almost the last vestige of Birmingham’s industrial past. You can still find Chamberlain Square in the city centre – but the chocolate factory is the real monument to the great Birmingham families.

Eventually, Cadbury family control of the company ended when it was sold to an American buyer, though the Bournville works remain. Now that Dunlop tyres and the Longbridge car factory have both closed, it is almost the last vestige of Birmingham’s industrial past. You can still find Chamberlain Square in the city centre – but the chocolate factory is the real monument to the great Birmingham families.

Richard Vinen is professor of history at King’s College London. His latest book is Second City: Birmingham and the Forging of Modern Britain (Penguin, 2022)