ANNIVERSARIES

Helen Carr highlights events that took place in April in history

23 APRIL 1349

The prestigious Order of the Garter first gathers

Edward III founds an elite club to celebrate war and encourage his nobles to fight in France

Honi soi qui mal y pense” – “Shame on him who thinks evil of it”. Emblazoned on heraldry across the centuries since 1349, this is the motto of the Order of the Garter – the oldest and most prestigious order of knighthood in Britain. The first wave of members of this elitist fraternity established by Edward III included his eldest son, Edward of Woodstock, later known as the Black Prince, alongside major English nobles who had fought during the first phase of the Hundred Years’ War.

The fraternity met annually, with the first gathering held on St George’s Day, 23 April 1349. The members each wore a blue robe with a golden garter on the left shoulder, and convened in St George’s Chapel, the “temple of chivalry”, at Windsor Castle. There the Knights of the Chapel were separated in two, with one faction led by the king and the other by the Black Prince, possibly representing teams in royal tournaments, or opposing sides in battle.

The Order of the Garter was Edward III’s contribution to the glorification of war, particularly recent victories at the battle of Crècy and the capture of Calais. Commemoration and pageantry became a major part of the Edwardian agenda, promoting his martial ambitions. His reign was steeped in Arthurianisms: he installed a “Round Table” at Windsor, and in 1344 some of his men swore an oath to search for the Holy Grail.

Through the establishment of the Order, Edward also elevated Saint George as an icon of war and of Englishness. His creation of the Order – membership of which was highly desirable – aimed to promote chivalry and incentivise war for the leading nobility of the realm, with the mythical figures of Arthur and Saint George spurring them on.

The tradition continues with the annual Garter Day procession each June, in which the king and the Order’s Knights proceed to St George’s Chapel, sporting velvet robes and plumed hats.

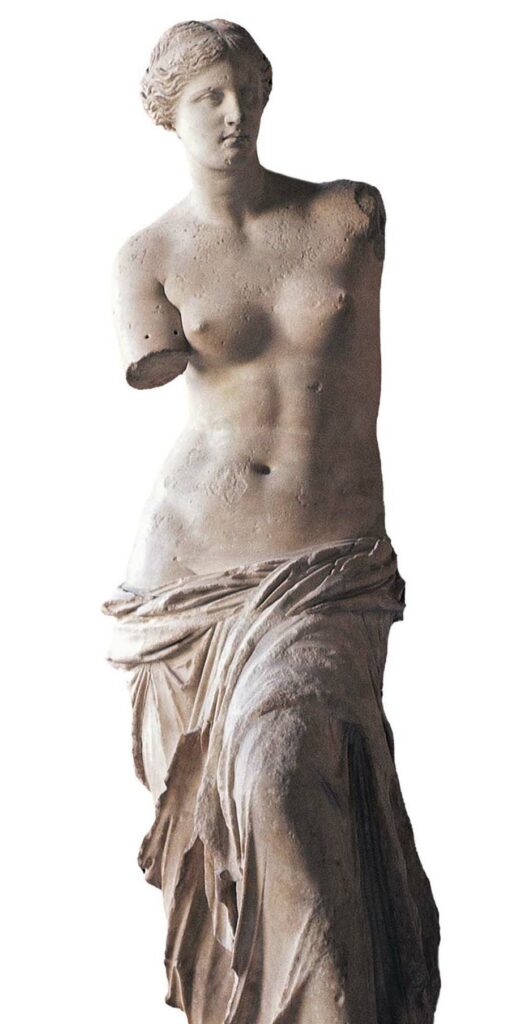

8 APRIL 1820

The Venus de Milo is discovered by a Greek farmer

The marble figure of an idealised woman reappears two millennia after its creation

Apeasant farmer clearing stones from scrubby land, a rock removed to reveal a long-hidden wonder, an icon reborn. That’s the most commonly told account of the discovery of the Venus de Milo, one of the most revered artworks in history – though, as with her identity, the truth is rather less than certain.

In 1820, Milos – a small island in the Cyclades between Athens and Crete – was part of the Ottoman empire, though subject politically to the French. According to the most widely recounted version of the story, on 8 April, Yorgos Kentrotas uncovered a niche holding a statue carved from Parian marble. Seeking help to recover his find, Yorgos alerted French naval officer Olivier Voutier, whose ship was docked nearby and who himself was looking for antiquities. He recognised the fractured find – the armless torso of a woman, swathes of fabric draping her hips – as something special, and the French ambassador was persuaded to buy the statue for 1,000 francs.

The following February, the so-called Venus de Milo reached the Louvre, where she was presented to Louis XVIII – though the king was so obese that he could not immediately access the room in which she was displayed.

The identity of the figure, carved in the second century BC, is still debated. She may be the sea goddess Amphitrite, worshipped on Milos. However, a fragment of a hand holding an apple suggests that she depicts Aphrodite – or Venus, to the Romans.

15 APRIL 1912

In the early hours of the morning, as the band plays on, the “unsinkable” Titanic goes down off Newfoundland, having struck an iceberg just before midnight. Some 1,500 people will perish.

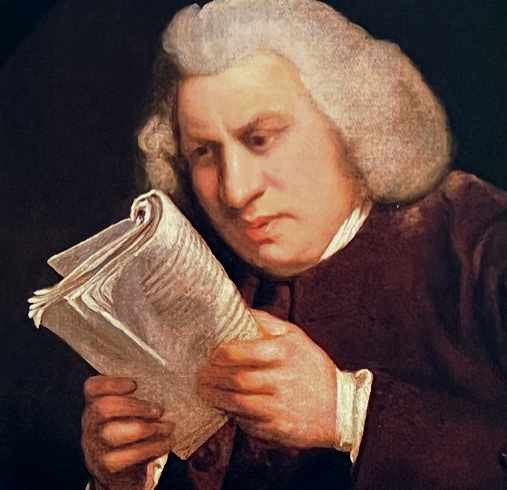

15 APRIL 1755

Dr Samuel Johnson publishes his magnum opus, the result of eight years’ diligent work: A Dictionary of the English Language.

14 APRIL 1775

The first abolition society in North America is established in Philadelphia. Membership of the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage is dominated by Quakers.

13 APRIL 1598

The Edict of Nantes ends France’s wars of religion

Promises of religious freedoms bring to a close almost four decades of bloodshed

The second half of the 16th century was a bloody period in France. For decades, tension had been building between the country’s dominant Roman Catholics and Huguenots. Those adherents to a Calvinist brand of Protestantism had grown in influence, particularly in southern and western France. In 1562, this friction sparked an outbreak of violence, launching nearly four decades of religious conflict that divided the nation and quickly descended into civil war. Covert murders and daylight massacres were committed by both sides – most infamously in the form of the horrific St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in Paris in 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were slaughtered by Catholics.

The dynamic changed fundamentally with the accession in 1589 of the first Bourbon monarch, Henry of Navarre. He was, though, crowned Henry IV of France only in 1594 – after he converted to Catholicism, having been raised as a Protestant. By then, a more tolerant and amiable approach to religious differences had been diplomatically formulated in an effort to end the conflict. And on 13 April 1598, Henry signed the Edict of Nantes, in that city of the Loire region. The 92-article edict, which decreed civil unity and religious toleration on both sides, succeeded at least partly in restoring religious harmony and bringing an end to the bloodshed. By its terms, Huguenots would be free to worship publicly, but only in 200 specifically named towns and on land owned by Huguenots. They were, though, allowed to worship in their own homes nationally, were given the right to education, hospitals and inheritance, and could own property and trade freely.

Even after Henry’s conversion to Catholicism, some people continued to harbour doubts about his true faith. Sceptics suggested that his efforts to promote freedom of worship were indications of residual Protestant leanings, and continued to object to the edict’s terms. This simmering resentment had dire consequences for the monarch. In 1610, Henry was assassinated by François Ravaillac, a Catholic zealot.

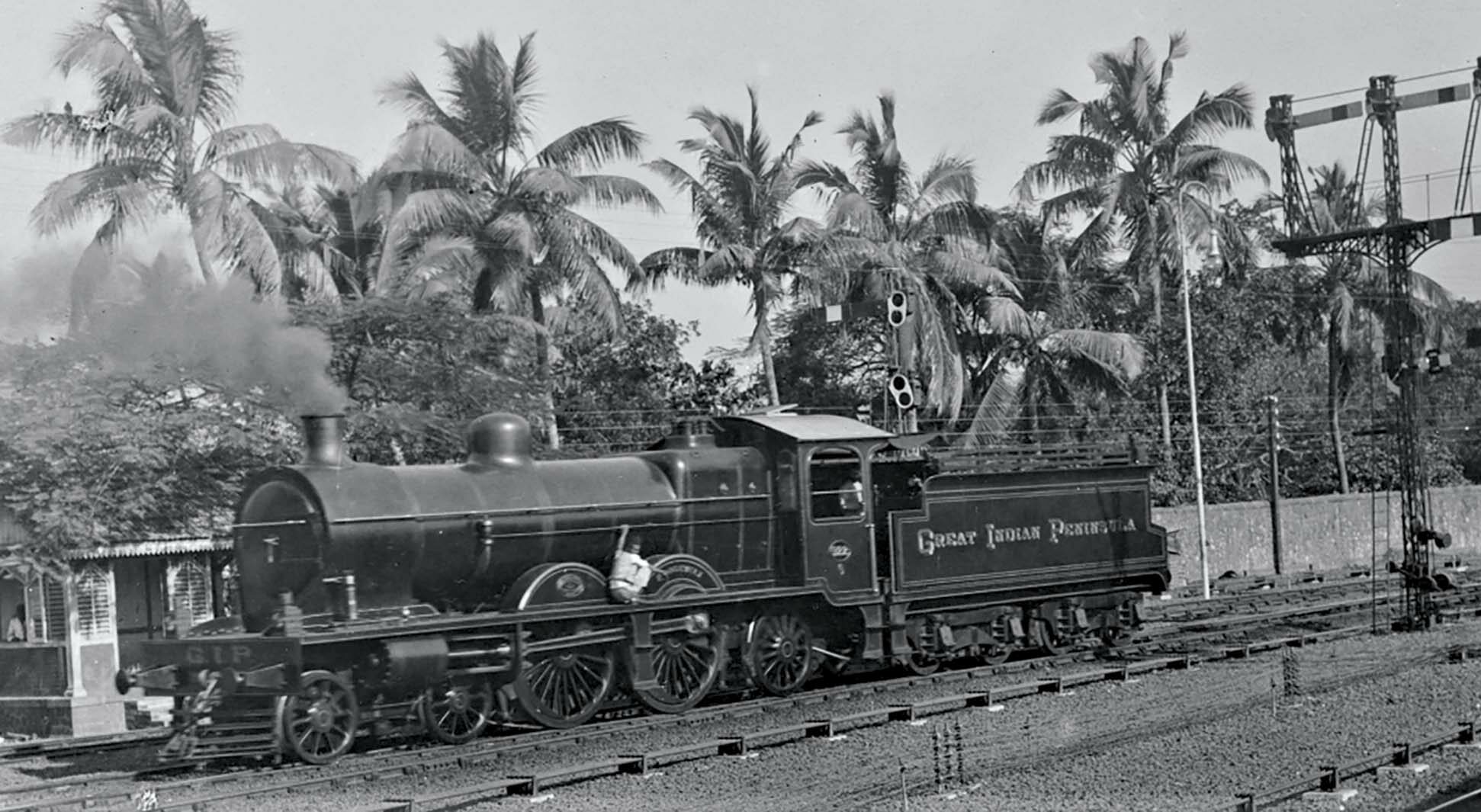

16 APRIL 1853

The first passenger train in India chugs out of Bombay

Three steam locomotives haul 500 passengers on the inaugural 21-mile journey

A powerful wind blew across the 100-metre-long platform at Bori Bunder train station in Bombay (now Mumbai). Clouds of dust whipped through the air, stinging the eyes of the throng of “European ladies and European and native gentlemen” who had gathered on the platform in the early afternoon of 16 April 1853. They had come to witness the departure of the first passenger steam train on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway – and, as it would later transpire, the birth of what became one of the world’s largest railway networks.

At 2pm, those 500 lucky passengers invited to embark on the momentous journey were ushered into the 14 stationary carriages, and three huge black locomotives named Sultan, Sind and Sahib began to build up steam. At 3.35pm, as a 21-gun salute was fired from the ramparts of Fort George, the train chugged away on the first passenger railway journey in India – indeed, in all of Asia. Along the entire 21-mile journey to Tannah (now Thane), taking just under an hour, the train and its excited passengers were cheered by thousands of spectators lining the route.

The event caused quite a stir, and not only in India, where Britain’s empire was at its peak. That pioneering train journey made headlines in the broadsheets of the imperial capital, too. A newspaper report claimed that the inauguration of the first passenger railway on the subcontinent was even more significant than British “victories in the east, which seem tame and commonplace”. It went on to assert that “the opening of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway will be remembered by the natives of India when the battlefields of Plessey, Assaye and Gujarath have become the mere landmarks of history”.

Today, this seems a tasteless comparison, measuring industrial development against acts of violence committed during Britain’s colonisation of India. Nonetheless, the advent of this Great Indian Peninsula Railway paved the way for one of the most extensive and successful railway networks in the world.

Helen Carr is a historian and writer. Her latest book is The Red Prince (Oneworld, 2021)