COMMENT

Michael Wood on… The history carried in our landscapes

“Destroy a river and you also lose its past, part of our collective memory”

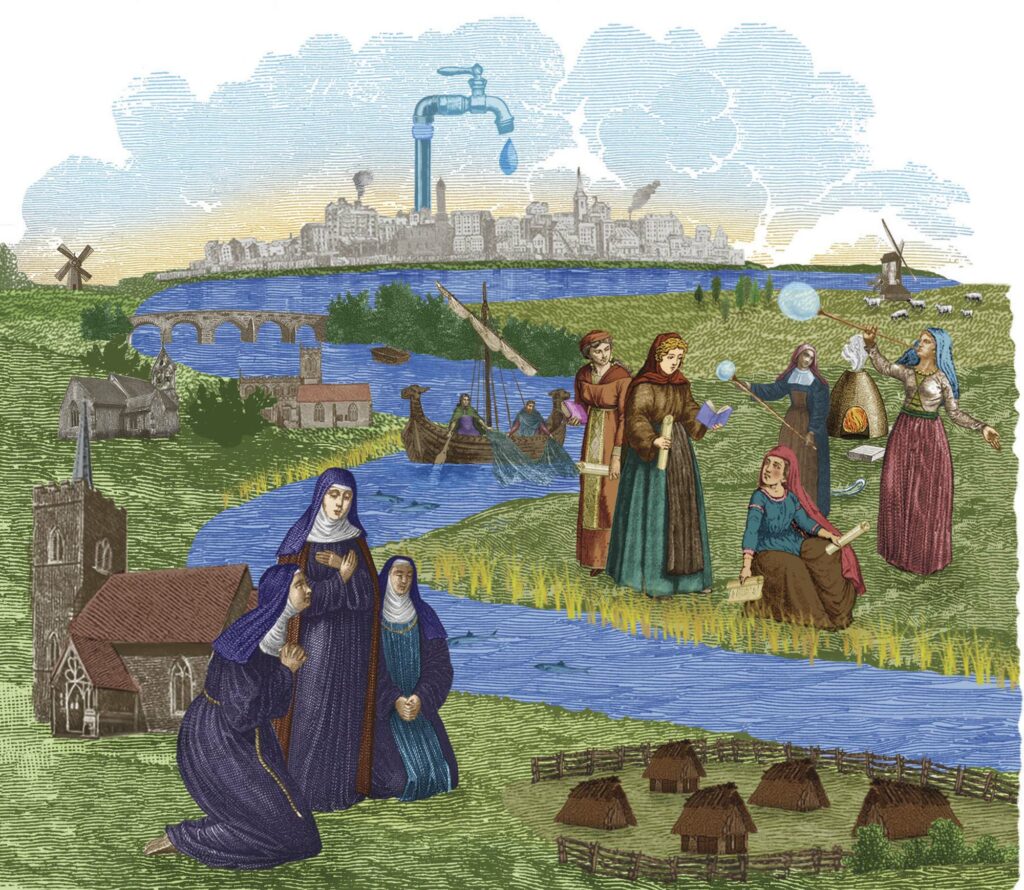

The other day, I took the District Line to Barking for an urban history walk along one of London’s forgotten rivers, the Roding. This waterway flows into the Thames at Barking Creek, near the site of a famous seventh-century Anglo-Saxon nunnery. Close to the tube station, Abbey Green Park today marks the site of the monastic enclosure that was sold off to Henry VIII’s cronies for building stone. Little remains above ground, but excavations have picked up signs of medieval craft activity, a water mill, glassmaking – traces of what for nine centuries was a centre famous for female learning.

Just beyond the abbey gardens, you reach the Roding. The river rises near the Suffolk border, on the plateau where Stansted Airport now stands, and flows down under the M25 and along the North Circular Road to the Thames, a distance of more than 30 miles. Walking its banks to Ilford and Wanstead, you pass medieval churches, a mosque, a Sikh gurdwara, a Hindu Durga temple – our entire history unfolding in one landscape.

In ancient times, the river wasn’t called the Roding. In its lower reaches it was known as Hyle (as in Ilford), from an old Celtic word meaning something like “the trickling stream”. But this is one of those rare cases where a river takes its modern name from the settlements on it, rather than the other way round. Farther upstream, in the hills above Ongar, eight villages (originally nine) are still known collectively as the Rodings – in old dialect, Roothings – the largest group of same-name villages in Britain. The name means the settlements of the “people of Hrotha”, who was presumably the chief of an early group of Saxons who settled the area after the fall of Rome, perhaps in the sixth century. So the territory of today’s eight parishes was the land of the Hrothingas. Such archaic “inga” names represented small tribal groupings in the age before shires and kingdoms. Traces of others survive elsewhere: the Stoppingas around Wootton Wawen in Warwickshire, the Feppingas in Worcestershire. So even now our landscape preserves memories of people who lived here long before England existed. Here is an idea to hold onto: the locals are the people of the river, but the Roding is the river of the people.

In medieval documents, we can glimpse the lives of the Roding people – the Saxon small holder Saemaer, with his water meadow, his 10 cattle and his beehives; the “certain freewoman” with her priest, her eight farm workers and her two slaves on the eve of the Conquest in 1066.

Our urban walk along the Roding, though, casts a dark shadow over what we will be passing down to our descendants. In this once-beautiful landscape, the river has been abused, its very existence threatened. Channelled into concrete underpasses, strewn with rubbish, polluted with chemicals, dumped with garbage by developers and builders, its life has been thoughtlessly and relentlessly squeezed. At Ilford – where in medieval and Tudor times there was an abundance of good water, a watermill and even a fishery – there have recently been sewage outfalls into the river under the North Circular Road.

So it has been left to a heroic group of local volunteers and activists, the River Roding Trust, to try to save the Roding and its landscape. On weekends, they fill black bags with rubbish thrown into this once-lovely river that, with its rich meadows, has been the “common stream” sustaining and enriching life along its banks for so many centuries. They have taken developers to court over the right to walk the riverbank. In the fightback, they are planting new trees, stands of willows and riverside shrubs and flowers. Guerrilla gardening, indeed!

The health of our rivers is vital to everyone. If you love history, it is even more pointed, for in our landscapes are carried all our histories. Destroy a river and you also lose its past; it is akin to losing part of our collective memory. We live in times of the degradation of landscapes across the world, caused by poverty but also by the deliberate actions of the rich and powerful. And in Britain these disasters threaten not only our environment and our physical and mental wellbeing but our history, too. The volunteers working to save the Roding riverscape, taking our common duty to nature seriously, deserve our heartfelt thanks – for doesn’t nature, too, have rights? I imagine Hrotha and his folk are looking down approvingly.

Michael Wood is professor of public history at the University of Manchester. He has presented numerous BBC series, and is the author of several books including The Story of China (Simon & Schuster, 2021). His Twitter handle is @mayavision