HIDDEN HISTORIES

Kavita Puri explores lesser-known stories from our past

“A broad reckoning with the Cultural Revolution is still far off in China”

I spend a lot of my time thinking about historical memory, about when we choose to speak – or to forget – both as individuals and collectively. I also think about how memory shifts, how it surfaces and retreats depending on the wider contemporary context, and how it evolves as it is passed down and becomes second- and third-hand remembrance.

I was reminded of this while reading an excellent new book, Red Memory: Living, Remembering and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution (Faber & Faber). When its author, Tania Branigan, was working as The Guardian’s China correspondent between 2008 and 2015, she found that the stories she covered would invariably link back to the Cultural Revolution. It was, she says, inscribed not only in China’s economics, politics and culture, but also deep in hearts and minds. “It is impossible to understand China today without understanding the Cultural Revolution,” she writes. “Subtract it and the country makes no sense: it is Britain without its empire, the United States without the Civil War.”

Branigan recounts some astonishing and harrowing stories, including those of a son who denounced his mother – leading to her death – and of a teacher suspected of being a counter-revolutionary, beaten with nail-spiked clubs and left to die on a rubbish cart in the hot sun.

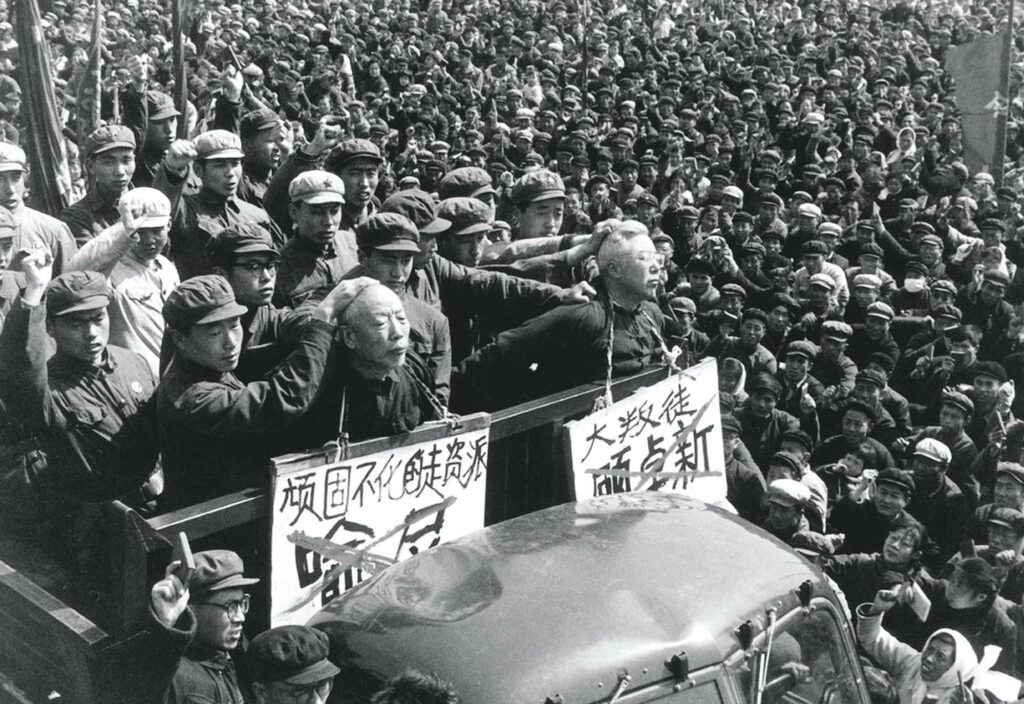

After Mao Zedong’s disastrous Great Leap Forward project to modernise China’s agricultural system resulted in famine and millions of deaths, in 1966 – in an attempt to contain dissent – he launched an all-out assault on “class enemies”. Hundreds of thousands more people are believed to have been killed in the decade that followed. “It consumed the country in its entirety,” says Branigan. “No workplace remained untouched. No household remained innocent. ‘Complicity’ is too small a word – comrade turned on comrade, friend upon friend, husband upon wife and child upon parent. You could build a career on such betrayals, until the currents shifted once more and the victims turned upon you.”

Yet hundreds of millions who lived with its consequences rarely spoke about that time – because they were not allowed to, or because they feared repercussions. If the Cultural Revolution had taught people anything, it was the need to keep one’s head down. Others kept their silence because it was too unbearable to remember. Branigan believes that the Chinese Communist Party, and those it rules, have also conspired in this amnesia.

Finally, things started to change – online and in more daring publications. Red Guards began to talk about their past, and families spoke of relatives who had been killed. A significant number viewed the Cultural Revolution with nostalgia. Others shared secrets – their fears and their guilt that had been hidden for decades.

Then, when Xi Jinping took power a decade ago, the atmosphere began to chill. “Though the Cultural Revolution’s legacy is more relevant – more evident – than ever, this book could not be written if I were to begin it today,” observes Branigan. Xi decried “historical nihilism”, and a hotline and website were set up to encourage citizens to report transgressions. Magazines such as Annals of the Yellow Emperor, which once ran groundbreaking articles on recent history, were taken over and muzzled. Archives were closed, memorials sealed.

A broad national reckoning is far off. It is hard to heal such a collective trauma. An added complication is that the party is implicated in the Cultural Revolution; its leaders may well fear that acknowledging the past may bring to the surface historical dissent or old grudges. The deep-rooted fear of speaking out prevails once more.

Yet in the absence of discussing openly what happened, what is publicly remembered and what was recorded, silence can still be felt. There may be a political will to forget that decade, but its memory cannot be erased from the people who lived through it. It will live on in ways we don’t yet know, to be passed on to coming generations.

Kavita Puri is a journalist and broadcaster for BBC Radio 4 whose history series include Three Pounds in My Pocket. She is also the author of Partition Voices: Untold British Histories (Bloomsbury, 2019)