Hitler’s aristocratic admirers

George VI’s Nazi dilemma

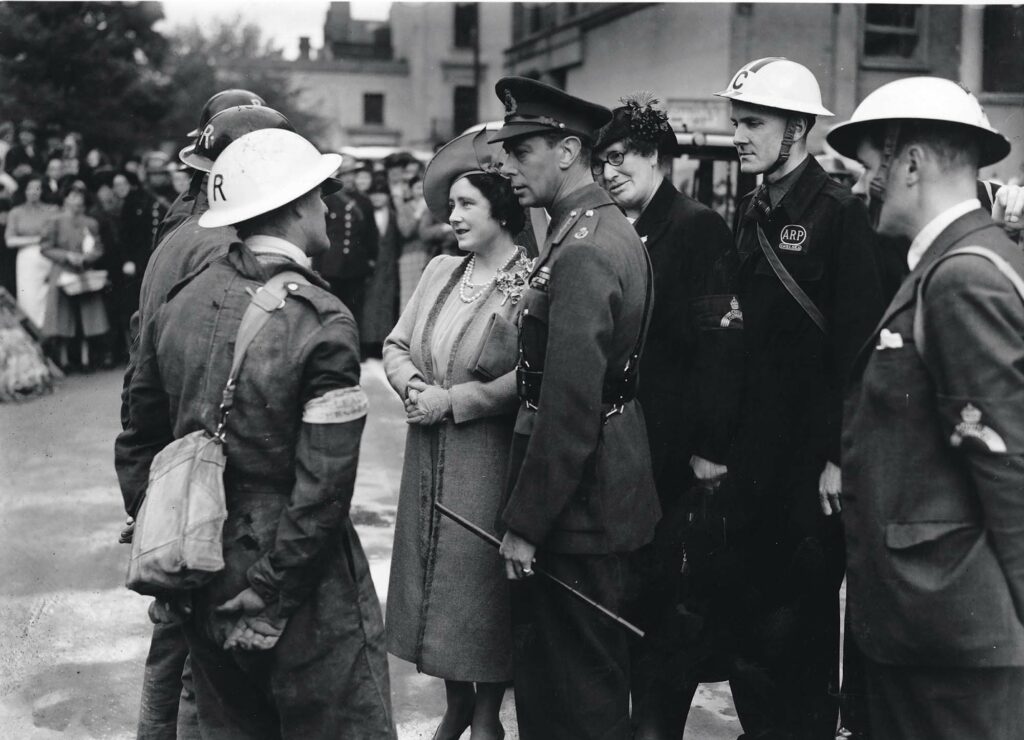

As war raged across the globe, the king had to confront admirers of Adolf Hitler uncomfortably close to home, writes Alexander Larman

“I NEVER THOUGHT HITLER WAS SUCH A BAD CHAP”

THE DUKE OF WINDSOR, SPEAKING TO LORD KINROSS, c1965

Even today, 80 years after the Second World War, these words retain the power to shock. But when the Duke of Windsor reportedly uttered them to Lord Kinross in the 1960s, few in the upper tiers of the British establishment would have been surprised by the sentiments. The former Edward VIII has been described as the “traitor king” on account of his perceived fascist leanings, of which his belief that Hitler was “not such a bad chap” was almost the least egregious.

Edward’s sympathies were well-known enough by 1940 for Winston Churchill to write an initial draft of a letter – later diplomatically toned down – to the other prime ministers of the Commonwealth that stated: “The activities of the Duke of Windsor on the continent in recent months have been causing [His Majesty] and myself grave uneasiness as his inclinations are well known to be pro-Nazi, and he may become a centre of intrigue.”

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor had visited Germany in October 1937, a trip organised by the Nazi-sympathising industrialist Charles Bedaux as a quid pro quo for having hosted their wedding at his French chateau earlier that summer. The Windsors had met Hitler, and were given a curated tour of Germany as an energetic, forward-looking country, led by a near-messianic figure.

The duke came away from the visit with a positive impression of the führer – who hosted him for a private audience at his holiday home at Berchtesgaden – and wrote a letter of thanks on 23 October in German for the “wonderful time” they had had. He stated that “the Duchess of Windsor and I would like to thank you sincerely for the great hospitality you have shown us, and for the many options you gave us to witness all that has been done for the working people of Germany. Our trip through Germany has made a great impression on us, and we won’t forget the attentiveness you surrounded us with and the warm welcome we received everywhere.”

Had he known that hosting the British aristocracy had been a Nazi speciality since Hitler’s rise to power, Edward might have felt less unique. Yet given the pro-appeasement sentiments that many of the upper classes held in the approach to war, coupled with an admiration for the British fascist leader Oswald Mosley, Edward should have known that he was among fellow travellers. That the man who used to head the empire was on the wrong side during the gravest national crisis that Britain had ever faced should have been a dreadful anomaly. Unfortunately for his country, it was not.

The reason why some British aristocrats were drawn to Hitler and fascism was not simply admiration for the well-cut uniforms. Instead, the führer was seen as a vigorous reformer who had transformed a struggling and bankrupt country in record time, through methods that might have seemed brusque, even harsh, but nonetheless had paid off spectacularly. Given that many of the British upper classes, including the royal family, had their own German links through family connections, it seemed as if what had been achieved in Germany could, and probably should, be imported to Britain, too.

This was an opinion held by Walter Scott, Duke of Buccleuch, who occupied the symbolic but important position of Lord Steward in the royal household. This was a post that had existed since at least the 15th century, and its holder was nominally in charge of royal expenditure. Previous stewards had included Robert Dudley, Elizabeth I’s rumoured favourite. It was a sinecure given to someone considered worthy of trust, but in this case, royal confidence was misplaced.

Buccleuch was a man of substance in 1939: Britain’s largest landowner, brother-in-law of the king’s brother the Duke of Gloucester, and a decorated war veteran. He was also someone who held not merely pro-appeasement views, but pro-Hitler ones. He wrote to the politician Duff Cooper in October 1938 to say: “Can any of us prove or judge in advance that it is impossible under any circumstances to trust Hitler or Germany?” and made a number of personal visits to the fatherland in the lead-up to war, where he was an intimate of many of the leading Nazis. He even hoped to attend Hitler’s 50th birthday on 20 April 1939, but was informed by a courtier that his presence would “not [be] all square with the present feeling of the king’s government”.

Hamilton had links to a Nazi agent who MI5 described as a “close associate of Hitler“

War didn’t dampen Buccleuch’s dedication to improving Anglo-German relations. On 12 December 1939, he wrote a letter to George VI in which he stated: “I can hardly presume to put before your majesty too many of my own opinions, but they are shared by a large and growing number of your majesty’s most loyal subjects, and among them many wise and distinguished citizens. I and others have felt keen disappointment that there were not efforts of a rather different nature and greater perseverance to establish a closer contact with the German leaders in the early part of last summer.”

Buccleuch suggested that war had been caused by “press campaigns, rumours, insults and propaganda”, and that the conflict had blinded the country to its true enemy, Soviet Russia. He concluded that “from continuous evidence I do not feel the nation is as united for war as is frequently stated, but naturally one does not wish to disclose any disunity”.

It was an implicit threat to royal authority, and, after initially ignoring it, the king was forced to ask Buccleuch for his resignation in May 1940. He dismissed the Lord Steward’s proselytising – “I, and the bulk of my people, feel that the Nazi regime is an evil one, and one which has so far spread nothing but misery and cruelty in the little peaceful countries which have the misfortune to be neighbours to Germany” – and ended with his own warning to Buccleuch not to cause further discord. “The queen and I know that you will do all in your power to help this country in her great need, and we do feel so sorry that your opinions preclude you from standing by us at this moment.”

The king summed up his Lord Steward’s departure on 26 June 1940 in his diary. “It was a rather painful interview as he has been ‘dubbed’ as being pro-German in his attitude towards the war and has said stupid things, but we parted amicably.”

Matinee-idol charm

Buccleuch’s replacement as Lord Steward needed to be above suspicion, and the aviator Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, Duke of Hamilton, seemed the perfect match for the role. One of the first men to have flown over Everest, he possessed matinee-idol charm and charisma. Unfortunately, no due diligence went into his appointment. Otherwise, it would have become clear that Hamilton had his own links to the Nazi party. He had attended the Berlin Olympic games in 1936 as a guest of Joachim von Ribbentrop, a former champagne salesman and confidant to Hitler who had served as German ambassador to Britain between 1936 and 1938.

This was embarrassing enough, but Hamilton’s actions were not so exceptional in the context of upper-class appeasement to be seen as remarkable or dangerous. However, it transpired in 1940 that the new Lord Steward was a correspondent of Albrecht Haushofer, a Nazi agent who MI5 described as “a close associate of Hitler and. . . on personal terms with most of the Nazi hierarchy”. When Hamilton was asked about his connections with Haushofer at an interview at the Air Ministry on 11 March 1941, he not only admitted knowing him, but had hosted him on frequent occasions during his visits to Britain. He described Haushofer as a “patriotic German”, who, along with his father Karl – who MI5 called “a man of great influence in Nazi circles” – was trying to be a restraining influence on Hitler, largely without success.

“Perhaps the post of Lord Steward is bewitched, or is it Germanised?” asked the king

MI5 remained unconvinced that Hamilton was wholly innocent: their official report stated: “Our records do not give us any positive proof of any pro-German or anti-British activities, but it is felt that it would not have been surprising if the duke had allowed himself to be used as an intermediary for these terms during the blackest period of the war last summer.”

MI5 devised a plan – although there is no evidence that it was executed – to dispatch Hamilton to see Haushofer in the neutral city of Lisbon, in order to elicit information as to the state of feeling among supposedly more moderate Nazi party members. It was perhaps no coincidence that, two months later, Hitler’s deputy, Rudolf Hess, crash-landed 10 miles south of Glasgow. Hess had been aiming for Hamilton’s home of Dungavel House in South Lanarkshire.

Hamilton was allowed to interview Hess, and was uncomfortably reminded of his previous intimacy with the deputy führer; Hess not only recalled meeting Hamilton during the Olympics, but suggested that his freelance embassy to Britain, seeking peace terms, had been suggested to him by their mutual friend, Haushofer.

Lingering suspicions

It soon became clear that Hess had miscalculated, and his belief that he could convince the king to accept a treaty was constitutionally incorrect. Yet the propaganda value that his arrival in Scotland offered Britain would be undone if Hamilton’s loyalties were at all questionable.

The secretary of state for air, Sir Archibald Sinclair, announced in the House of Commons on 22 May that “the conduct of the Duke of Hamilton has been in every respect honourable and proper”. Yet that didn’t stop suspicion hanging over both Hamilton’s relations with Hess and the wider Nazi party. The king wrote incredulously in his diary on 13 May 1941 that “I had to ask Walter Buccleuch [Hamilton’s predecessor] to leave owing to his sympathy with the Nazis. Perhaps the post of Lord Steward is bewitched or is it Germanised [?]”

Nonetheless, Hamilton could not leave his post, due to the embarrassment that a second departure would have caused. He remained Lord Steward until 1964, albeit with the lingering suspicion of his Nazi associations forever upon him.

After the Hess incident, there were no more high-profile statements of solidarity with fascists from leading aristocrats; the public humiliation, or worse, would have been too great. Yet it’s likely that many more than the Duke of Windsor continued to believe, privately, that Hitler was “not such a bad chap”.

SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL

What drew British elites to Hitler’s dark ideology?

Although many British aristocrats supported appeasement, few went so far as to express their public allegiance to Hitler after the outbreak of war. The likes of Josslyn Hay, Earl of Erroll – a supporter of the British Union of Fascists, but still a guest at the coronation in 1937 – and Viscount Rothermere, the Daily Mail proprietor who notoriously wrote the editorial “Hurrah for the Blackshirts!” in 1934, now chose to keep their counsel.

Yet silence did not mean that they had changed their opinions. Many were frustrated by a country that (so they believed) had denied them preferment. They looked at the way that the likes of Joachim von Ribbentrop had acquired power in Germany, and hoped that they might do the same.

Hitler’s highest-profile aristocratic supporters were the Mitford sisters Diana and Unity. Diana, who was married to Oswald Mosley, remained an unrepentant fascist sympathiser until her death in 2003. Late in life, she accepted that Hitler was “a monster”, who was “very cruel and did terrible things”, but also praised him as “obviously an interesting figure”. MI5 documents released in 2002 suggested that she was “far cleverer and more dangerous than her husband”.

Her sister Unity’s relationship with Hitler, who she called “the greatest man of all time”, was even stronger. Not only were they rumoured to be lovers, but she tried to kill herself at the outbreak of war with a gunshot to the head, out of grief at the situation. Unity never fully recovered from her wounds and died in 1948, aged 33.

Alexander Larman is an author of historical books and biographies. His most recent is The Windsors at War: The Nazi Threat to the Crown (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2023)

PODCAST

Why did Nazism appeal to the upper classes?

Alexander Larman will be discussing aristocratic admirers of Hitler on our podcast. Listen here: historyextra.com/podcast

LISTEN

To listen to a documentary on Edward and Mrs Simpson from BBC World Service’s Witness History, go to: bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p00fvjp1