Crime and punishment / Amazing lives

William Douglas

The infamous bushranger

Hard drinker, bandit, prize-fighter and reader of skulls. Meg Foster unravels the myth of “Black Douglas”, whose life of crime across 19th-century Australia made him a target of lynch mobs and the popular press

In May 1855, hundreds of Victorian gold miners moved to lynch a gang of alleged murderers and thieves. The Alma goldfields in the Australian colony of Victoria saw between 100 and 400 diggers set out to punish a nefarious criminal, named Black Douglas, and his brothers in crime. They knew Douglas as a dastardly goldfields’ entity, a black colonial bogeyman accused of a slew of serious crimes including violent robbery and (though all evidence suggests he wasn’t guilty) the murder of a white woman on the diggings at Avoca. The lynching was averted after a policeman convinced the miners it was in their best interests to bring in Douglas and his men to face British justice (Douglas was sentenced to two years’ hard labour). “It will give very general satisfaction to the public to be informed that the career of this notorious criminal and his mates in crime has sustained a check,” declared one report.

Douglas was renowned as a “bushranger” – a bandit who robbed to survive and hid in the Australian bush on the run from the law. While some white bushranging men gained assistance and local fame for their criminal deeds in this period, appearing as colonial Robin Hoods to some of their working-class supporters, Douglas was cloaked in infamy. The miners did not concern themselves with the details of Douglas’s life, or verifying the heinous stories told about him. They knew Douglas by reputation as a black man and a criminal, and that was enough for them. But Douglas’s time on the goldfields was just one small part of his epic life story. And there is far more to his tale than immediately meets the eye.

Black Douglas was American. Born William Douglas, in Philadelphia in 1817, he entered the world with some luck on his side. Douglas was one of the first generations of black Americans to have been born legally free from slavery and enforced labour, as Pennsylvania was an abolitionist state. It had ushered in the first state enforced programme of emancipation in the world with the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780. Philadelphia, in particular, was known as a hub for runaway slaves and a centre for free black thought and culture. From the late 1820s, Philadelphia was home to thriving black literary societies that provided their own schools and education. This was a remarkable feat considering that, at this same time, reading was viewed as a seditious skill for enslaved people in the American south.

“Douglas was cloaked in infamy but the gold miners did not verify the heinous stories about him”

This is not to say that Douglas had an easy life. Racial hatred grew as the 19th century progressed. Many citizens of Philadelphia began to fear and resent the new free black population of which Douglas was a part. Douglas undoubtedly experienced racism and may have predicted its increase. This might have been why he left. By 1835, William Douglas was living in England.

The most likely way that Douglas could have journeyed thousands of miles from North America to Britain was as a seafarer, perhaps working for his passage on board a trading vessel. Douglas was described later in life as a cook/ servant, and he may have occupied these roles on a ship – they were, after all, common occupations for someone of Douglas’s race and youth.

In some ways, seafaring would have offered Douglas more freedom and equality with his peers than he found on land. Men were more likely to be employed according to their skills rather than their ethnic origins, although this didn’t mean ships were free from the grip of racism. Ships relied on hierarchy and absolute obedience to one’s superiors. Crew members with more power could arbitrarily punish members lower down the ladder and could use racial slurs to demean their lessers.

Hard hand of justice

If Douglas was indeed employed on a trading vessel, it wasn’t for long, for soon he was working as a labourer in England. And it was here that he first encountered the hard hand of British justice.

In January 1835 at the age of 18, Douglas was brought before the Rye Quarter Sessions in Sussex. Alongside a man named John Smith, he was accused of stealing two woollen coats, the property of a Charles Taylor. Caught red-handed in the act of the theft, the odds were not in Douglas’s favour. He and Smith were found guilty and sentenced to seven years’ transportation to New South Wales. The verdict was expected. The sentence was not.

Although transportation was a common punishment in early 19th-century Britain, in Rye it was far from the norm. Rye had control over its criminal justice system, but it usually sent those accused of serious offences to the Sussex Assizes. Douglas and Smith were tried and punished severely in Rye to serve as an example of the government’s robust stance on crime, and as a deterrent to any like-minded criminals.

The next leg of Douglas’s international journey was coerced, as he was shipped across the world to the Australian colony of New South Wales as punishment for his crime. Life in the colonies was not to his liking. During his six years in New South Wales, Douglas received 336 lashes and spent 12 months working in irons for various misdemeanours and crimes, from being absent without leave and neglect of work to assault. By 1841 it seems that Douglas was so unsatisfied with convict life that he tried to leave it. In 1841, he bolted into the bush to become a bushranger.

“After serving his sentence, Douglas was one of hundreds of ex-convicts who flocked to the gold rush in Victoria”

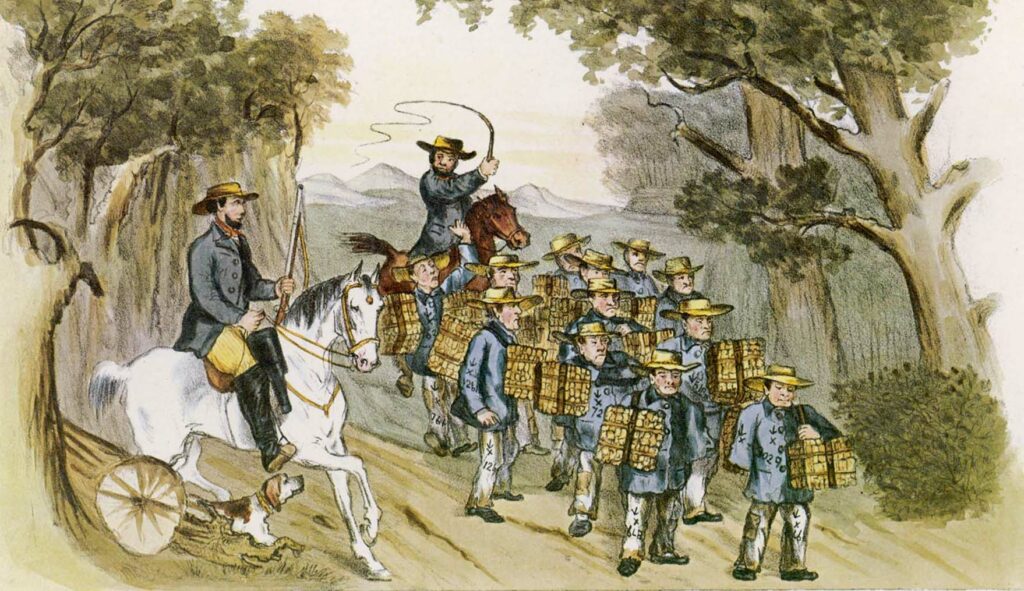

Despite goldfield rumours to the contrary, this was the one and only time in Douglas’s long life that he committed bushranging crime, and it was incredibly anticlimactic. Douglas and an accomplice named John Wood held up a cart at Seven Mile Hollow, robbed it of “blankets, some tea, sugar and other property”, according to the Sydney Herald, and were captured soon after fleeing the scene. The Sydney Monitor noted: “[The man in the cart] recognised Wood, but Douglas, who is a man of colour, had a black handkerchief over his face, but [the] prosecutor knew him to be a man of colour by his hands.”

For this crime, Douglas was tried and sentenced to be transported again; this time to the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land (present day Tasmania). Van Diemen’s Land was a place of secondary punishment – a site to send convicts who had committed new crimes in the Australian colonies. It was designed to both instil fear in offenders and to reform them through a coercive system of labour. The work was incredibly varied – from clearing land to providing domestic service for private settlers – but given Douglas’s record, it’s likely he would have been employed in heavy physical labour. Convicts’ situation would improve if they served enough time with good behaviour, but if they resisted the system, they were punished.

William Douglas chose resistance. In his nine years on the island, he was punished for 32 separate offences ranging from misdemeanours like drunkenness and obscene language, to serious crimes like riotous behaviour and assault. Douglas remained a recidivist despite the fact that in Van Diemen’s Land he received punishments of 49 months and 14 days’ hard labour. He also suffered eight bouts of solitary confinement, totalling some 60 days in isolation.

Taller and longer

But in Van Diemen’s Land, Douglas not only made a name for himself as a criminal. He was also a renowned prize-fighter. Although prize-fighting was illegal in Van Diemen’s Land at the time, these matches drew large crowds, and champions held a great degree of local fame. The moniker “Black Douglas” actually originated here, in the ring, as William Douglas’s prize-fighting name. One news report described him as 13 stone and “much taller and longer in the reach than his antagonist” – which meant the punters were “inclined to be sweet upon him”.

Douglas was not to stay in Van Diemen’s Land forever. After serving his sentence, he was one of hundreds of ex-convicts who flocked to the colony of Victoria during the gold rush of the 1850s. There, he became known as the “infamous Black Douglas” and was regularly referred to as “infamous” and “notorious” by newspapers. There’s no evidence he ever looked for gold himself, and instead he made his money from illicit pursuits such as sly grog-selling.

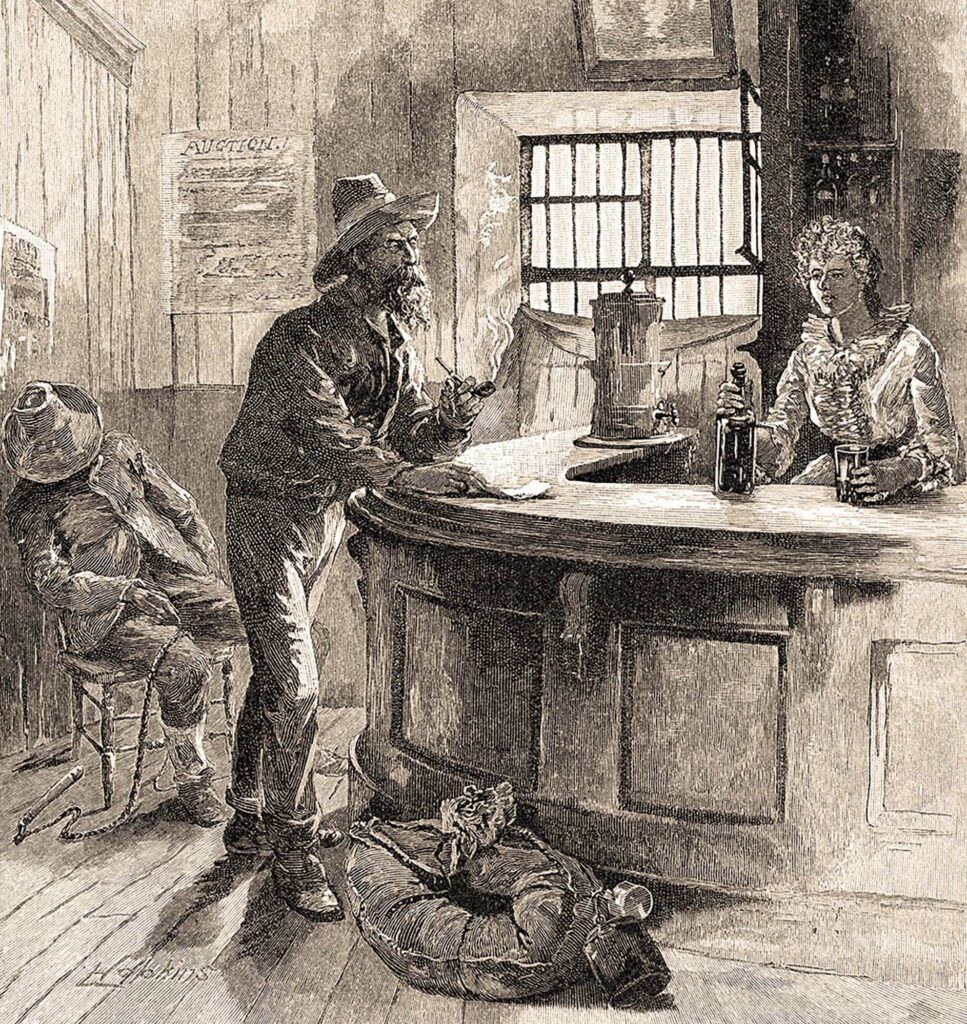

Douglas became a symbol of endemic crime on the diggings. Most of the diggers were white men, though the diggings also included Chinese, Maori and indigenous peoples, as well as white women. The white male miners were shocked and discomforted by the fact that people they believed to be their inferiors could find success on the diggings. A story casting a black man as a villain who murdered a defenceless white woman made sense to them and restored their ideas about racial and gendered order. But rumours of murder and high-stakes robberies were just that: rumour. In reality, William Douglas was a petty criminal, who was most often convicted for alcohol-related offences on the diggings. In 1853, his own words, rarely heard, appear in the historical record. At a court hearing he “complained that police were always pouncing on him and that he had a bad reputation without a cause”.

After his goldfield adventures in the 1850s, Douglas was constantly in and out of gaol for vagrancy and drunk and disorderly conduct. He died in Bendigo gaol in 1892 from old age and senile debility.

Douglas lived his life in prison, on the streets, in benevolent institutions, or in the pub. A pub may not appear to be an obvious place to challenge colonial ideas about race, but it was here, late in life, that Douglas became a phrenologist – a turn of events briefly recorded in his anonymous obituary. Phrenologists believed that by “reading” a person’s skull, they could divine details about their character and intelligence. Phrenology was also intimately intertwined with racial science, as white phrenologists used their “studies” to justify white people’s place at the top of the racial ladder. And yet, at the same time, Douglas, a black man in a pub, was “reading” white people’s skulls in exchange for a pint.

Meg Foster is a research fellow at the University of Cambridge and author of Boundary Crossers: The Hidden History of Australia’s Other Bushrangers (NewSouth, 2022)

PODCAST

How gold changed the world

Stephen Tuffnell explored the history of gold rushes on our podcast. Listen here: historyextra.com/gold-rushes-qa