MEDICINE

Mind games

Andrew Scull is entertained by a critical but witty examination of early psychoanalytical practitioners and their self-absorbed patients

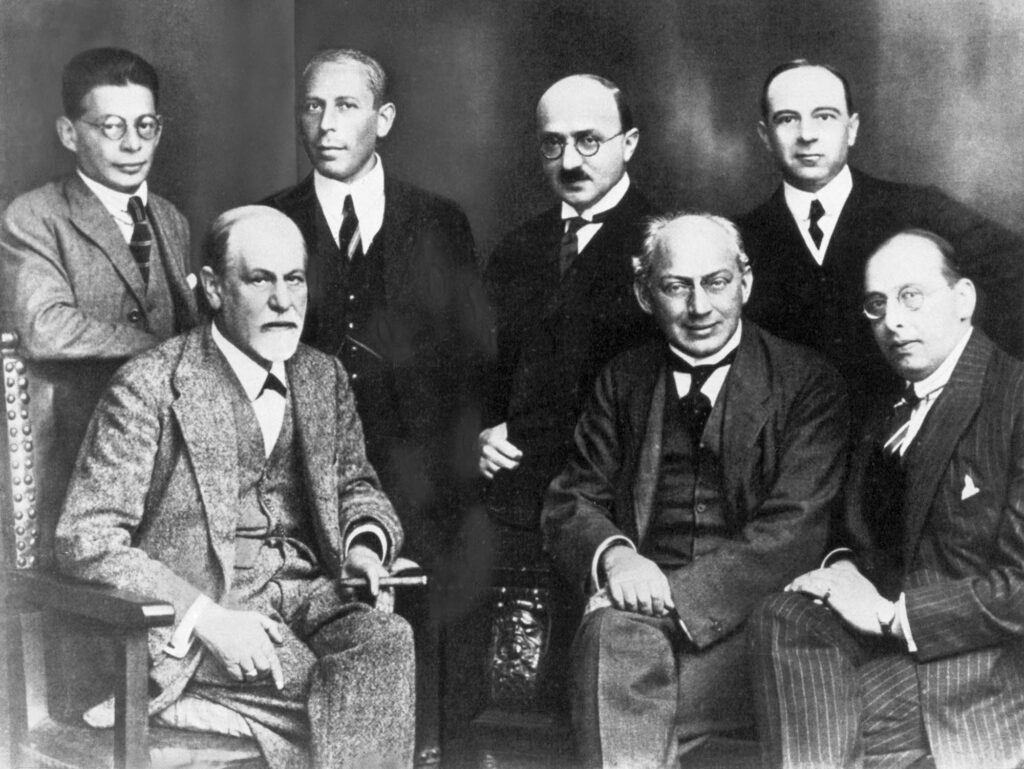

In his new book, Seamus O’Mahony invites readers to view the shifting fortunes of three men over the course of nearly four decades. The guru in question is Sigmund Freud; the bagman is his most devoted disciple, Ernest Jones; the sceptic is Jones’s brother-in-law, eminent surgeon Wilfred Trotter. There’s a particular focus on psychoanalysis – which the author, like Trotter, clearly regards as a cult, not a science. “Psychoanalysis,” he remarks, “became a home for rich directionless strays, who analysed other rich directionless strays.”

If O’Mahony is essentially dismissive of Freud’s intellectual legacy, he displays a grudging respect for the man himself. Trotter, the sceptical Englishman, with his dexterity as a surgeon and his innate modesty, is most sympathetically portrayed. Least favoured is the industrious but sycophantic Jones, whose peccadillos and limitations are laid bare.

While still young men on the make, Jones and Trotter were close friends. That friendship became strained when allegations of sexual abuse prompted Jones’s abrupt departure from London to Toronto in 1908. More scandals surfaced in Canada, forcing Jones to return to London in 1913. By then he had become a convinced Freudian, and soon built a lucrative practice. Within a few years, Jones “effectively controlled the London market in psychoanalytic patients” and made a handsome living, coming to own several properties including a summer house on the French Riviera.

Jones also acted as “Freud’s agent and broker”, sending him a steady stream of rich English patients. Freud was duly grateful, thanking him for “providing well for my medical income”. However, he disliked Jones and quashed his hopes of marrying Freud’s 18-year-old daughter, Anna.

“O’Mahony dispenses caustic judgments about those attracted to psychoanalysis in the interwar years, and about its practitioners”

In recounting this history, O’Mahony dispenses caustic judgments about those attracted to psychoanalysis in the interwar years, and about its practitioners. “Psychoanalysis was the opium of the intellectuals,” he concludes, and “as influential in Cambridge in the 1920s as communism in the 1930s”. He has little doubt about why: “Cambridge intellectuals discovered that they liked nothing better than talking about themselves… The dressing up of this prolonged immersion in the self as a ‘scientific’ and ‘therapeutic’ process was intoxicating.” The other hotbed of English psychoanalysis was Bloomsbury. “Freudianism appealed to the Bloomsberries because it was simultaneously avant-garde and elitist, and because it legitimised their unorthodox sexual behaviour.”

Many patients later joined the ranks of the analysts. The only qualifications these “couchjumpers” possessed were their own sessions with Freud, who then gave them his personal imprimatur. O’Mahony holds most of these in little regard. The snobbish and casually antisemitic Joan Riviere, among Freud’s more able translators, is described as “one of the great monsters thrown up by psychoanalysis in England”. James Strachey, who translated Freud’s work, and Adrian Stephen, Virginia Woolf’s brother, were “dabblers who had failed at everything else, [until] in early middle age they found something they could finally stick at”. As for Melanie Klein, the child psychoanalyst who did so much damage to her own children’s lives, O’Mahony’s verdict is succinct: she was “truly wicked”.

This is not a book for those enamoured of Freud and his followers. Others will find much here to relish – the Freudians were a rum lot. O’Mahony has a sharp eye for their foibles, and writes with wit and humour.

Andrew Scull is distinguished professor of sociology and science studies at University of California, San Diego

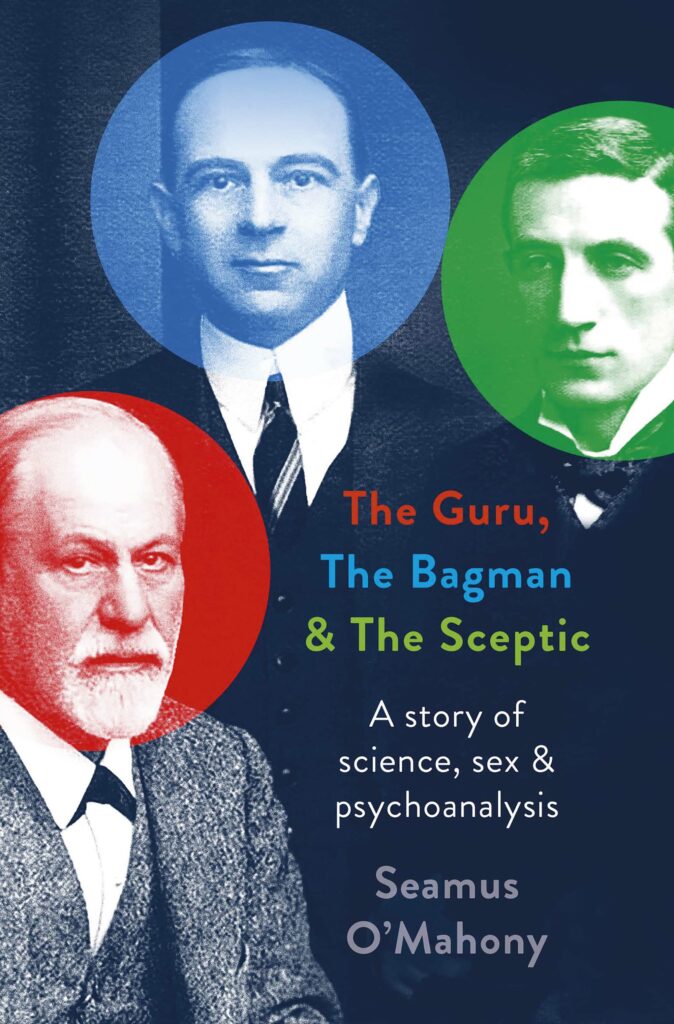

The Guru, the Bagman and the Sceptic: A Story of Science, Sex and Psychoanalysis

by Seamus O’Mahony

Head of Zeus, 336 pages, £27.99

All products were chosen independently by our editorial team. Below is an affiliate link, and we may receive a commission for purchases made. Please read our affiliates FAQ section underneath the Letters page to find out more.