SURPRISING FACTS

7 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Vietnam War

Jem Duducu shares facts about the era-defining conflict in which the US attempted to halt the spread of communism in southeast Asia

1 The Vietnam War isn’t called that in Vietnam

The name itself shows a non-native understanding of the conflict. Instead, the two decades of fighting in Vietnam, from 1954 to 1975, are called “the American War”. The Vietnamese made the assumption that the foreign forces who fought in that war were all Americans, but they were not: large numbers of Thais, South Koreans and Australians, to name but a few, fought on the side of South Vietnam.

2 The conflict had roots in 19th-century French imperialism

In 1858, Tourane (modern Da Nang) was attacked and captured by the French admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly. After leaving a small garrison in place to hold the city, he then journeyed south and captured Saigon (today’s Ho Chi Minh City) in early 1859.

This started a century of French occupation, and most of the southeast Asian peninsula (including Vietnam) was renamed French Indochina. The indigenous population was never completely cowed, so rebellions and guerrilla attacks were regular occurrences. The Vietnamese rebels used the dense jungles and mountainous terrains to their advantage in order to attack French forces and escape detection.

During World War II the region came under the control of pro-Axis Vichy forces and Japan, so the Americans armed and trained local forces to fight against them. After the war France tried to reclaim the area, but the better-trained and better-equipped guerrillas defeated France once and for all at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

3 The Vietnam War didn’t only take place in Vietnam

The poor choice of name for the war fails to reflect how much of southeast Asia it affected. The French had been using Vietnam as a launch point for hostilities against both Burma (now also known as Myanmar) and Thailand (previously Siam until 1939), so it was unsurprising that fighting leaked out of Vietnam’s borders. The main reason for this was the so-called Ho Chi Minh trail, a supply line that stretched along the spine of the entire country that enabled the communist powers in the north to supply the communist guerrillas (the Viet Cong) in the south.

However, most of this road network was actually located in neighbouring Cambodia and also ran through parts of Laos. The regular bombing of both countries took place under the orders of American presidents Lyndon B Johnson (in office 1963–69) and Richard Nixon (1969–74).

Unlisted CIA plans (black ops) were also carried out. They were unofficial (and illegal), as America had never formally declared war or confirmed to the public that combat operations were taking place in either Cambodia or Laos.

The instability caused by this unofficial military activity allowed the communists of North Vietnam to help support a communist revolution and civil war in Cambodia. This would lead to the formation of the Khmer Rouge regime (in power from 1975–79), which was responsible for the infamous Cambodian genocide.

4 The conflict was part of the Cold War

Technically, the Vietnam conflict was a civil war, with the communist North fighting against the anti-communist South (it was not a democracy and was run by paranoid dictator Nguyen Van Thieu). The country had never been split like this before; the two areas were artificial, with no natural boundary between them, so it was highly likely that one or both sides would attempt to reunite the country by force.

However, the North was backed by communist China and the Soviet Union, and the South was backed by western powers. But in practical terms, with respect to both finances and equipment, it was America that supported the South.

Vietnam became a testing ground for weapons. How well would the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk fare against Soviet-made S-75 Dvina surface-to-air missiles, for instance? Similarly, while the AK-47 had been in use for nearly 20 years, this was the first time it was used wholesale against the American M16. The AK, with the larger clip of bullets (30 versus 20) and fewer moving parts, meant that it rarely jammed and was the perfect jungle ambush weapon.

America (and others) feared that after China and North Korea had fallen to communism, Vietnam might well fall, too. If it went ‘red’, where would the advance of communism end? The concept was known as the ‘domino theory’ and hundreds of thousands of Americans were sent to Vietnam in order to fight against it.

5 The Vietnam War saw technical as well as political incompetence

Some of the grimmest stories about equipment malfunctions during the Vietnam War concern the M16 rifle. The guns were initially shipped from the US with incompatible ammunition, meaning that they would jam after only a few shots were fired; indeed, dead Americans were sometimes found in the jungle next to their stripped-down rifles, having tried and failed to dismantle, clean and rebuild their weapons after coming under fire. A later change of powder in the ammunition greatly improved the gun’s performance, but the large amount of plastic (rather than wood or metal) used to create the M16 gave it a toy-like quality, which inspired the saying “you can tell it’s Mattel” – the slogan of a popular American toy manufacturer.

Similarly, the Americans’ new Chinook helicopters were prone to catastrophic failures. Why? It transpired that ground personnel were overloading the cargo bays, assuming that the double-rotor helicopters could take the weight. They couldn’t. Multiple Chinooks crashed, killing their crews, all because of this fundamental fault.

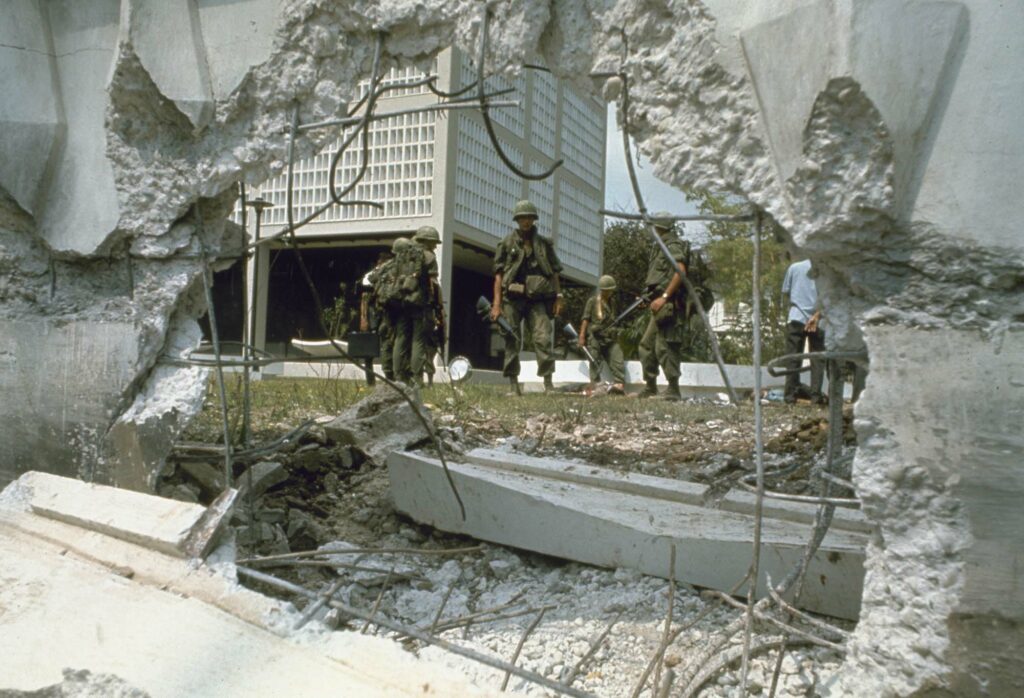

6 The Tet Offensive was not a military defeat for the Americans

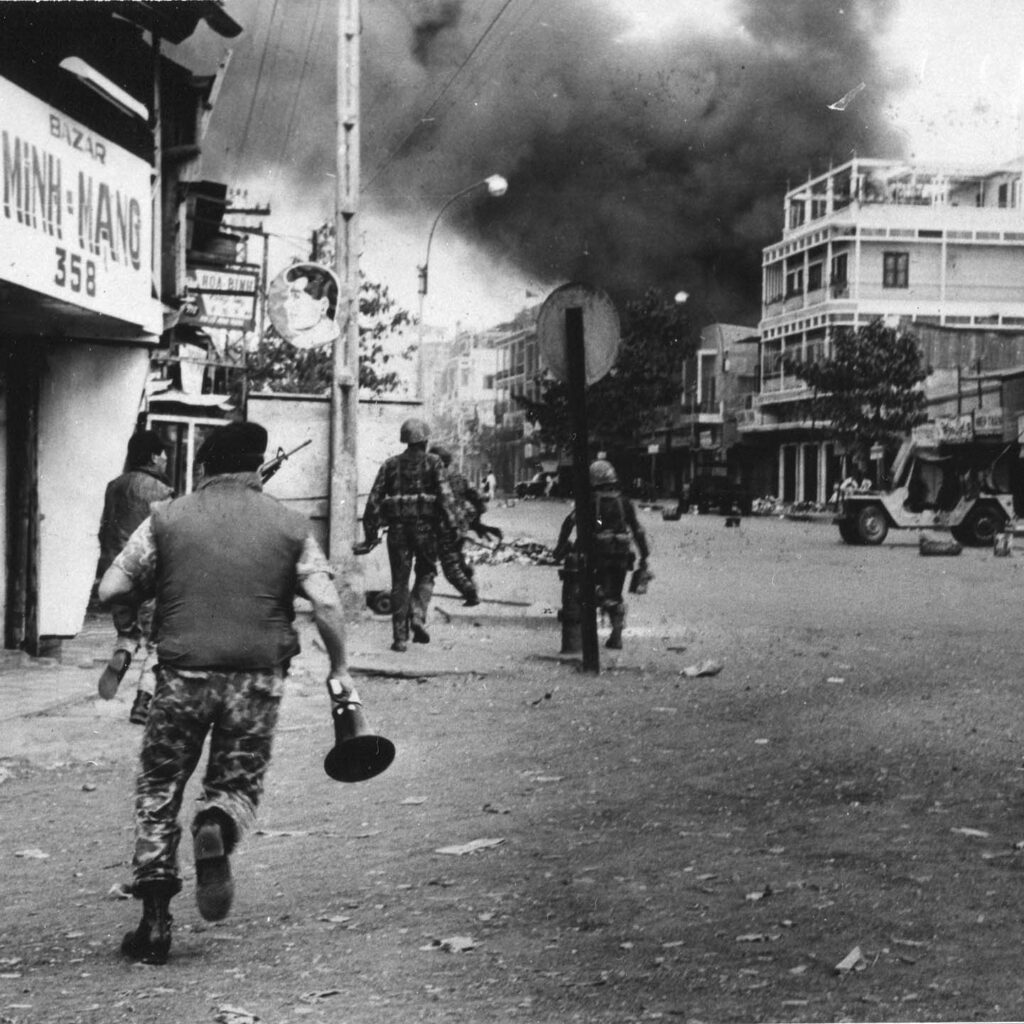

Tet is the biggest holiday of the year in Vietnam, and in 1968 there was an agreed ceasefire so that everyone could celebrate. However, the Viet Cong saw this as an opportunity to infiltrate a number of key cities in the south, from which they launched attacks on 31 January. Viet Cong commandos even assaulted the US embassy in Saigon, possibly the most heavily defended compound anywhere in the world. To many in the US, this seemed like a humiliating defeat for their forces in Vietnam.

The Americans’ fundamental problem during this war was locating the enemy. Up until Tet, most of the fighting had been in the jungles, where Viet Cong guerrillas surfaced without warning and disappeared just as suddenly, using the cover of dense foliage and a widespread network of tunnels. Now the Viet Cong were in an urban environment with no heavy artillery, armour or anything like the numbers of combatants compared to the Americans. Within weeks, the American forces annihilated the Viet Cong. The Viet Cong were never an effective fighting force on their own again after this offensive, and all subsequent combat operations were dominated by the North Vietnamese Army.

Tet was a devastating defeat for the communists, but it’s not remembered that way. The American military had been saying for more than a year that the Viet Cong were being constantly ground down. ‘Kill counts’ were reported on the US nightly news almost like sports scores. So by January 1968, America assumed the Viet Cong were on their last legs. For the Viet Cong to be able to mount such an ambitious offensive proved the American military had been either lying, or caught with their trousers down.

7 The Vietnam War is still going on in Vietnam today

While nearly 60,000 Americans lost their lives in the war, more than 3 million Vietnamese (both North and South, including civilians) also died. By the end of the war in 1975, America had dropped more than 7 million tonnes of bombs on Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos – more than had been dropped during the whole of World War II. In addition, thousands of tonnes of defoliant, known as Agent Orange, destroyed thousands of acres and poisoned the land, killing both humans and livestock and resulting in birth defects in unborn babies.

Both sides used landmines, and it is estimated that these, combined with unexploded ordinance, mean there are some 800,000 tonnes of explosives yet to be made safe in a country where 20 per cent of Vietnam’s total area is still thought to contain unexploded devices. In fact, it’s been estimated that since 1975 there have been 100,000 casualties (including 40,000 deaths) caused by these dangerous relics of the war.

In conclusion, the story of the Vietnam War combines 19th-century imperialism with 20th-century communist history and late 20th-century American foreign policy. It is a rich and complex era characterised by catastrophic misjudgments, ruthless cover-ups and tragic consequences on all sides.

Jem Duducu is a historian and author. His books include Echoes (2019), a work of fiction set during the Vietnam War, and the upcoming non-fiction title Hollywood and History: What the Movies Get Wrong from the Ancient Greeks to Vietnam, due for publication in June 2023

LISTEN

Professor Mark Atwood Lawrence answers questions about the Vietnam War on an episode of the HistoryExtra podcast from 2021: historyextra.com/vietnam-pod