CASTLE CONSTRUCTION

Grand designs

Part fortress, part luxury home, constructing the perfect castle required colossal amounts of money, men and patience

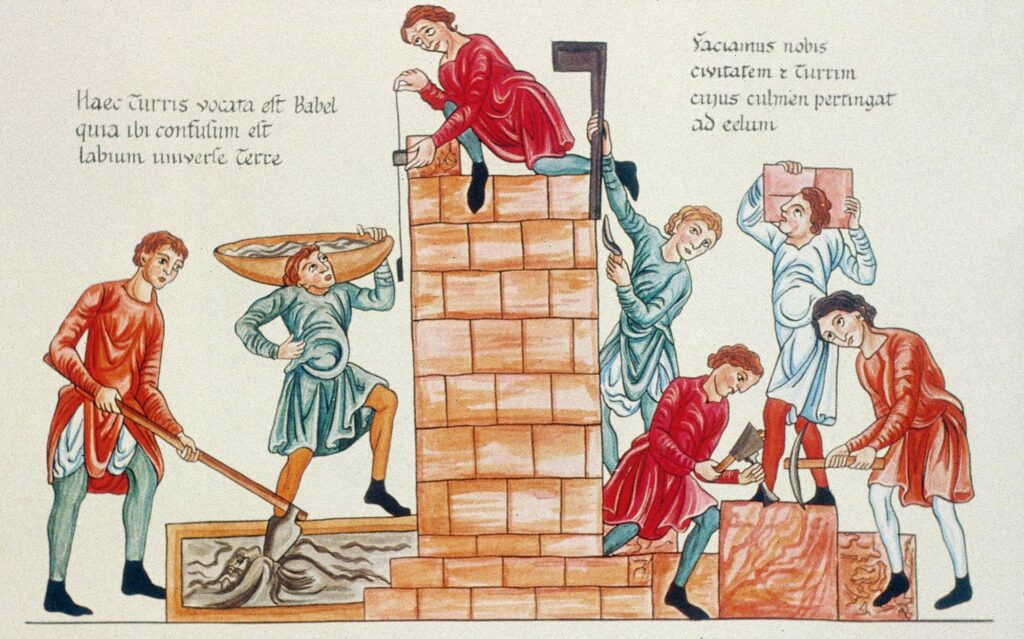

Building a medieval castle was a serious business. The construction site would be a hive of activity: thousands of workers would swarm over the structure, with stonemasons adding to half-finished walls, as a horde of carpenters scraped and sawed fresh timbers into roof beams or fashioned new tools. And the master mason – an architect, building expert and project manager rolled into one – would stride through the scene, making sure the castle was growing according to his exacting specifications.

The castle-building craze had first reached England in 1066, when William the Conqueror claimed the country for his own. The Normans – finding themselves in a hostile land – hastily built motte and bailey castles (comprising a large mound of earth topped by a tower, alongside a shallower enclosure for other buildings). England’s rich forests provided a steady – and cheap – supply of timber for these structures, and a crew of carpenters could hammer a tower together in a relatively short timeframe. However, these wooden structures had a clear drawback: they were vulnerable to fire. And, if they weren’t being besieged by angry Saxons, mother nature would also sink her teeth into the structures, rotting the wooden timbers.

So if wood was unsuitable for building castles, what could replace it? The answer was stone. It was impervious to the elements and would last for centuries, making it the ideal material for building defensible structures.

This was crucial, as castles weren’t simply lavish homes for nobles – they needed to withstand attacks, too. With this in mind, building materials weren’t the only important factor: location was also key. Strategic positions that had natural defences, such as a major river, were prized – or else sites that controlled a communication route, like a bridge or a pass. Once the location was decided upon, plans could start to be drawn up for the building itself. Castles were designed by master masons: senior builders who were as skilled with a quill as they were with a chisel, and used geometry to create their building designs.

The cause of labour

Planning the castle’s defences was a vital part of the process. Would it be encircled by a deep, water-filled moat? Would it have an iron portcullis at its main entrance, that could keep attackers out – or trap them inside, to be picked off by defenders? How many arrow slits were needed, and where? And how could defenders stop projectiles from wrecking the castle and allowing attackers to flood inside?

These defensive concerns were usually addressed by the master masons, who were sometimes referred to as ‘engineers’ on account of their ability to come up with ingenious designs. Often, they were called upon not only to build castles, but also to construct machines with which to attack them. Indeed, they knew how to utilise the devastating power of cannon, and could also design wooden catapults and ‘springalds’ – mechanical catapults that spat out large bolts. It was well worth stumping up the cash for their expertise: in 1266, Kenilworth Castle (see page 43) held out against Henry III’s troops for nearly six months due to its impressive water defences and catapult collection.

It wasn’t only the cost of hiring an engineer that was staggering, though. The labour costs were astronomical, as it took a small army of men to build a castle – and they could be working on it for up to a decade. For instance, when King Edward I started work on a castle at Flint (in northeast Wales) in 1277, within a month he had 2,300 workers on the royal payroll – including diggers, woodmen, carpenters, masons, smiths and charcoal burners. To source such a massive amount of labour, workers weren’t always enlisted willingly: Edward coerced men into serving him, and employed guards to make sure no one escaped.

“To source such a massive amount of labour, workers weren’t always enlisted willingly”

As well as the manpower, there was also the question of lugging resources to the castle. Although stone was excellent from a defensive viewpoint, logistically it presented quite a headache. How could you bring thousands of tonnes of heavy rock to a distant construction site? One solution was to transport loads via water, as the builders of Rochester Castle did: they brought hard-wearing Kentish ragstone to the site via the River Medway, as well as ferrying softer Caen stone all the way from Normandy at great expense, to fashion the castle’s fine fireplaces and window arches.

Huge amounts of earth often had to be moved, too, perhaps to be heaped into a huge motte or else dug out and removed to form expansive moats. In the 1270s, Edward I decided to redesign the Tower of London, encircling the castle with an enormous tidal moat. This required a huge ditch to be dug, which cost more than £4,000 – almost 25 per cent of the project’s entire budget.

With such massive amounts of money and resources on the line, then, it was crucial that the building work went off without a hitch. To make sure that the structure followed the master mason’s plans to the letter, workers used rope and pegs to mark out the castle’s design on the ground and then dug shallow foundation trenches.

To erect the massive structures, medieval builders drew on an arsenal of construction techniques – some of which had been in use since Roman times. One such method was the treadwheel crane, which was used to lift the stones up to build the walls. This crane was like a giant hamster wheel, big enough for a man to stand inside, and was connected to a pulley, a length of rope and a pallet. If you walked in one direction inside the wheel, the rope would rise, bringing the loaded pallet to the top of the wall; if you walked the other way, the rope would be lowered. Using this system, piles of stone could be winched high into the air, so stonemasons could build the imposing castle walls and towers.

All the mod cons

A castle wasn’t purely about defence: it was also someone’s home. Exactly as we do today, castle owners valued fresh water, on demand; a means of warming their home; and a place to relieve themselves. Water was often provided via wells, which could be staggeringly deep: Beeston Castle in Cheshire boasts a well that descends more than 100 metres. Fireplaces were the obvious way of keeping inhabitants warm, with Rochester Castle having hearths in all its main rooms. And toilets (often called garderobes) were typically built inside the castle, discreetly positioned together down a short stretch of corridor. This was entirely practical: by placing all the facilities in the same area, builders only needed to fashion one shared receptacle below for the castle’s sewage; and the addition of the short corridor helped to contain the stench.

Interiors were expected to be sumptuous. King Henry III in particular demanded opulence, ordering painters to adorn Winchester Castle’s great hall with a map of the world and a “wheel of fortune” in the mid-1230s. From the 14th century onwards, defensive concerns became less important – and aristocrats used their properties to show off their wealth. These grand sensibilities often extended outside, too: there was a great demand for swathes of parkland, where nobles could hunt and ride, and – as the Middle Ages progressed – an increasing desire for gardens.

Striking a balance between constructing a luxury home and an impregnable fortress was no easy task. But the master masons and their armies of workers were certainly up to the challenge, and built structures that continue to fascinate us today.

Doing it for real

A new castle has been under construction in France for over 25 years

The techniques of medieval castle-building are no longer a relic of the past. In the depths of the Guédelon forest, nestled in Burgundy, France, a dedicated team of craftspeople are building a brand-new medieval castle – with only the techniques, tools and materials that were available in the early 13th century at their disposal. (Although they do have to adhere to modern health and safety measures, hiding helmets under their straw caps.)

Since 1997, a roster of quarrymen, stonemasons, woodcutters, carpenters, blacksmiths, tilemakers, carters and ropemakers have been toiling in the forest, bringing their vision to life. When complete, the castle’s inner buildings will be guarded by circular towers and protected by high stone walls. This year, the carpenters are planning to finish the pigeon-loft tower’s roof, while the stonemasons continue to work on the twin-towered gatehouse. If all goes to plan, the castle should be finished by around 2030.