CASTLES TO VISIT

Great British castles

Looking for a castle to visit? You could do no better than to add these spectacular structures to your checklist

HARLECH GWYNEDD

A Welsh landmark and the site of bravery in the face of terrible odds

The song ‘Men of Harlech’ is as synonymous with Welsh culture as ‘Bread of Heaven’ and ‘The Green, Green Grass of Home’. And at the heart of this rousing regimental march is a tale of heroism and defiance – and one spectacular castle.

Sitting on a rocky crag in Gwynedd, Harlech is arguably the most spectacular of all the fortifications that Edward I built in north Wales during his campaign to subdue the country. The castle took just six years to build (in the 1280s) and is a classic example of the ‘walls within walls’ design.

The Men of Harlech referred to in the famous song are believed to be the Lancastrian defenders who, in the 1460s, held out against a massive Yorkist army during the Wars of the Roses before succumbing to overwhelming odds, the defenders enders (in the words of one poet) “shattered by the sound of guns”.

Yet this was far from the first time that the castle had come under attack. In 1404, Owain Glyndŵr, iconic leader of the resistance to the English occupation of Wales, captured Harlech and made it his main residence and court. This was too much for the English to endure, and in 1409 Henry of Monmouth (later to be Henry V) laid siege to the castle. This time, Harlech’s defenders were forced into surrender by a punishing bombardment. The castle fell under English control again but Glyndŵr escaped to fight another day.

KENILWORTH WARWICKSHIRE

Later owned by Elizabeth I’s favourite, the fortress was once at the centre of a huge rebellion

Kenilworth Castle, which stands sentinel over the rolling Warwickshire countryside, was once owned by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the famed admirer of Elizabeth I. Yet it was under a previous Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort, that the castle, whose massive keep dates to the 1120s, made its greatest contribution to English history.

It was from Kenilworth that de Montfort planned a huge rebellion against Henry III, lighting the touch paper for the Second Barons’ War (1264–67). De Montfort briefly got the better of the king before being killed at the battle of Evesham in 1265. Yet that didn’t bring Kenilworth’s role in the conflict to an end. For it was to the castle that de Montfort’s defeated allies retreated for one last – and doomed – stand against Henry’s rampant forces.

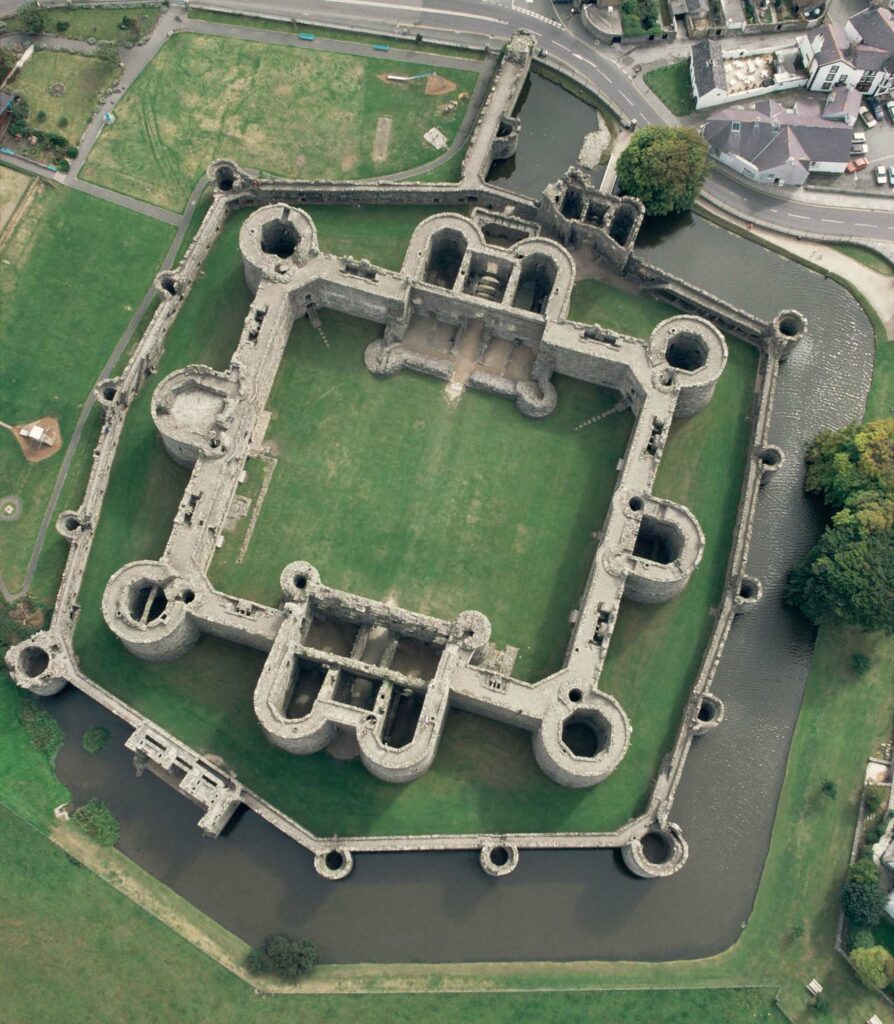

BEAUMARIS GWYNEDD

A true masterpiece of castle design on the Isle of Anglesey

Beaumaris has been described as Britain’s “most perfect example of symmetrical concentric planning”. And a visit to the castle, sited on the eastern shores of Anglesey, soon reveals why. Beaumaris was the last of the royal strongholds created by Edward I, and the lessons that the king and his architect James of St George learned at the likes of Harlech and Conwy were applied to stunning effect, producing four concentric rings of impressive defences, a moat and a dock.

Like a number of castles, Beaumaris was besieged by parliamentarian forces during the Civil Wars. Unlike other castles, however, it survived relatively unscathed following its fall, in 1646.

EDINBURGH CITY OF EDINBURGH

The nucleus of Scottish power

Sitting atop a mighty rock at the heart of Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh Castle has played a starring role in Scottish history since Iron Age people recognised its strategic value and built a fort here. Like Stirling, many of Edinburgh Castle’s most celebrated episodes took place during the Scottish Wars of Independence (1296–1357), perhaps none more dramatic than when Thomas Randolph, nephew of Scotland’s king Robert Bruce, seized the fortification from its occupiers following an audacious night raid in 1314.

The popular tourist destination now exhibits some of the most priceless artefacts in all of Scottish history, from the Scottish crown jewels to the iconic Stone of Destiny, an ancient symbol of the nation’s monarchy.

LINCOLN LINCOLNSHIRE

The castle that changed the course of English history – not once, but twice

Some of England’s most celebrated castles have witnessed little conflict during their centuries-long existences. Lincoln certainly isn’t one of them. The fortification – which is one of only two castles in Britain to boast two mottes (the other being Lewes in East Sussex) – was constructed by William the Conqueror two years after defeating Harold Godwinson at the battle of Hastings. William sought to put down an uprising in the Midlands and the North, and Lincoln was one of a chain of castles that the Conqueror built to subdue his recalcitrant new subjects.

It was in the mid-12th and early 13th centuries, however, that Lincoln found itself at the very centre of national events, staging two battles that changed the course of English history. The first occurred at the height of the vicious struggle for the English throne between King Stephen and Empress Matilda, now known as the Anarchy. It was while besieging the castle in February 1141 that Stephen’s forces were put to flight by an army loyal to Matilda. Stephen was captured and thrown in prison – and Matilda, for a short time at least, was the most powerful figure in England.

Lincoln Castle was engulfed by conflict again in May 1217 during the First Barons’ War, a conflict that saw Prince Louis of France (later Louis VIII) invade England with the support of a number of rebellious English barons. Louis had at some point held the upper hand, yet his hopes of victory were dashed at Lincoln when his troops were defeated and sent into retreat by an army loyal to Henry III.

Fighting on such a scale hasn’t returned to Lincoln over the past 800 years, but the castle remains a hive of activity today, remaining in use as a court.

CAERPHILLY GWENT

The design marvel that almost never happened

Caerphilly Castle is one of the greatest landmarks in south Wales. Boasting colossal walls, towers and gatehouses – and occupying a central island surrounded by artificial lakes – it looks as majestic today as it did in the Middle Ages. Yet it was very nearly never built. The English noble Gilbert de Clare’s attempt to construct a castle in the southeast corner of Wales in the late 13th century was scotched by his powerful Welsh rival Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, who burned the site in 1270.

Llywelyn’s power declined, however, with the rise of English king Edward I, and Caerphilly would evolve into a palatial residence, one whose concentric design became an exemplar for other castles across Wales.

CORFE DORSET

There’s a dark history hiding among this West Country castle’s impressive ruins

Corfe Castle’s majestic ruins – overlooking the tranquil village of the same name – belie a bleak, often violent history. The fortification rose out of the countryside during the reign of William the Conqueror. Yet it was under William’s descendant King John that the castle witnessed its darkest hour. Here, in 1203, the monarch ordered 22 knights to be starved to death in its dungeons.

Corfe would remain one of southern England’s most impressive castles until the mid-17th century, when it became the site of two sieges during the Civil Wars. A royalist garrison headed by Lady Bankes, wife of the Lord Chief Justice of Common Pleas, defied parliamentarian forces until 1646. Yet when the resistance collapsed, the castle was partially destroyed on the orders of parliament, leaving the ruins that welcome visitors today.

YORK NORTH YORKS

Witness to rebellion and a massacre

York Castle isn’t a single edifice but a complex of buildings. The most famous of them all is the castle keep, now better known as Clifford’s Tower, standing atop a motte just south of the city centre. It’s an imposing edifice – and, in all truth, it had to be, for York Castle endured a tempestuous early history.

The first castle, a basic wooden motte and bailey fortification, was captured and partially destroyed during fighting between York’s Norman occupiers and a Viking army supported by local rebels in 1069. Yet the castle’s darkest hour arrived in 1189, when local Jews were murdered or took their own lives after fleeing into the keep to escape an anti-Semitic mob.

WINDSOR BERKSHIRE

A home of kings and queens for more than 900 years

Windsor is arguably the most famous castle in Britain. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex were married here in 2018, Queen Elizabeth II was buried here and King Charles III is often resident here.

In fact, as the longest-occupied palace in Europe, Windsor has barely been out of the news since it was built to project Norman dominance along the Thames Valley at the end of the 11th century. Since Henry I moved in at the start of the 12th century, successive monarchs have added their own grand design statements over the past millennium. Yet it was built first and foremost as a fortification, as was proven by its ability to withstand a siege during the First Barons’ War.

TINTAGEL CORNWALL

The picturesque Cornish castle with connections to the Arthurian legend

Some castles are bigger. Some easier to reach. Others less impacted by the ravages of time. Yet when it comes to sheer mystique, few can compare with Tintagel. And much of that magic stems from the castle’s associations with one of the great legendary figures of British history: King Arthur.

Arthur was conceived at Tintagel – the product of a romantic liaison involving Uther Pendragon and the beautiful Igraine. That, at least, is what the 12th-century cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth tell us in his Historia Regum Britanniae (‘History of the Kings of Britain’).

Geoffrey’s account of Arthur’s conception and subsequent life may owe more to his vivid imagination than historical fact, but it certainly stuck. In fact, Tintagel has been intimately connected to the story of Arthur ever since. And that connection may have played a role in Richard, Earl of Cornwall’s decision to build a castle on this windswept headland in the 1230s. The remains of much of Richard’s building project – including two courtyards, a curtain wall and a gate tower – can still be seen today, despite 800 years of unforgiving Cornish weather. Tintagel slowly went into decline (and ruin) after Richard’s death but it never lost its power to fire the imagination. That much became obvious in the 18th and 19th centuries when artists such as Alfred Tennyson began romanticising the castle once more via paintings and prose. Today, courtesy of a new footbridge connecting the mainland to the headland, it’s never been easier to experience that romance for yourself.

DOVER KENT

The imposing ‘key to England’ that has often been at the centre of national events

Standing sentinel over the shortest crossing point between Kent and continental Europe, Dover was dubbed ‘the key to England’ by a 13th-century chronicler. This site was, however, home to fortifications long before the kingdom of England came into being. In fact, archaeology suggests that a fort might have stood here from at least the first century BC. What is certain is that the Romans made use of the location, building (among other things) an octagonal lighthouse – later converted into a bell tower – that still stands today.

William the Conqueror built a fortress at Dover shortly after the battle of Hastings, yet it was during the rule of Henry II (1154–89) that the castle received a makeover. In the last decade of his reign Henry constructed Dover’s mighty great tower, or keep, surrounded by a curtain wall studded with towers.

Dover was now one of the most technically advanced castles in the whole of Europe, a sophistication it exhibited on a number of occasions in the Middle Ages. It resisted determined sieges waged by Prince Louis of France in 1216 and 1217 during the First Barons’ War. A siege during the Second Barons’ War (1264–67) eventually ended in a negotiated settlement.

Dover Castle has witnessed less violence since the Middle Ages yet it has remained very much at the centre of national events. Henry VIII hosted the Holy Roman Emperor here in 1520, underground barracks were built here in the Napoleonic Wars, and during World War I the castle became the headquarters of a garrison comprising 16,000 troops. In the Cold War, it was even earmarked as a potential seat of government in the event of a nuclear attack.

PORTCHESTER HAMPSHIRE

Standing guard over the English Channel since Roman times

While many of Britain’s castles are the product of Norman craftsmanship, Porchester has a much longer history, stretching back to Roman Britain. Recognising the strategic importance of a location that overlooks Portsmouth’s natural harbour, in the third century the legions built what remains the best preserved Roman fort north of the Alps.

The Anglo-Saxons were the next to move in, occupying the remains of the Roman site from around the fifth century. But it was under the Normans that the castle’s impressive keep appeared. For centuries Portchester played a starring role in England’s tempestuous relationship with France, falling to a French invasion force in 1216 and acting as the launchpad for English campaigns across the Channel.

KIDWELLY CARMARTHENSHIRE

The centre of a tug-of-war between Norman and Welsh warlords

A network of castles are dotted along the coast of south Wales – evidence of centuries of conflict between the native princes and Norman lords. Few are more impressive than Kidwelly, rising above the River Gwendraeth in rural Carmarthenshire, and few changed hands more times.

Kidwelly was built as a Norman ‘ringwork’ castle in the early 12th century and soon came under attack from a series of Welsh princes, including the Lord Rhys, who captured it in 1159. The castle passed back into the hands of Anglo-Norman lords before falling to Llewelyn the Great, bane of King John and Henry III, in 1231.

Kidwelly has enjoyed a quieter existence since the end of the Anglo-Welsh wars. In fact its greatest claim to fame in the past century is, perhaps, appearing in the opening scene of Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

PEMBROKE PEMBROKESHIRE

The cradle of the very first Tudor monarch

The 28th of January 1457 was a turning point in British history. Not that anyone knew it at the time. On that winter’s day in the heart of the 15th century, a teenaged noblewoman named Margaret Beaufort gave birth to a son who would grow up to defeat Richard III in battle at Bosworth. The son’s name was Henry Tudor and (as Henry VII) he would go on to found one of England’s most celebrated royal dynasties.

Pembroke Castle had occupied a strategic site in southwest Wales since the late 11th century. A century later it came into the possession of the medieval period’s most famed knight, William Marshal. It was Marshal who ordered the building of the great round keep that dominates the castle today.

ALNWICK NORTHUMBERLAND

An impressive English castle prized by the Scots

Nestled in Northumberland, in England’s northeastern corner, Alnwick Castle found itself in the front line of the recurring conflicts that erupted between England and Scotland across the Middle Ages. Just four decades after it was constructed by the Norman noble Ivo de Vescy at the end of the 11th century, the fortification was captured by Scottish king David I. Some 40 years later, the Scots were back again, this time under William the Lion, who besieged the castle twice in the 1170s (before being captured by English forces outside the town).

The year 1309 was a landmark one in Alnwick’s long history, for it was then that the castle came into the possession of the powerful Percy family, who have lived here for much of the past 700 years. It was probably at the end of the 15th century that the castle’s impressive barbican was built, helping make Alnwick the second largest inhabited castle in the UK.

STIRLING STIRLINGSHIRE

A rallying point during the brutal Wars of Scottish Independence

The 13th and 14th centuries saw England and Scotland involved in a titanic battle for supremacy (now known as the Wars of Scottish Independence) – and Stirling Castle was invariably at the heart of the action.

Guarding the lowest crossing point of the River Forth, Stirling appears to have been an important royal centre from at least the early 1100s. Yet it was from the end of the 13th century, when Edward I of England launched an invasion of Scotland, that the castle gained its iconic status. The English occupied the castle at the end of the 1290s yet were dislodged following William Wallace’s famous victory over the invaders at nearby Stirling Bridge. The castle also played a pivotal role in the story of another heavyweight of Scottish history, Robert the Bruce. In 1314, while the castle was again in English hands, a force was sent north of the border to help ward off a Scottish siege. However, that army was soundly defeated by Bruce’s forces at Bannockburn, in sight of the castle walls.

Stirling would swap hands on a number of occasions until 1342, when it permanently fell under Scottish rule. From then on, it became the preferred residence of a string of Scottish rulers, including James IV, the renaissance monarch who spent a great deal of money trying to make the castle fit for an enlightened European king. Mary, Queen of Scots was crowned in Stirling Castle in 1543 and it was here that her son, James VI, was baptised before going on to reverse centuries of Anglo-Scottish enmity by uniting the two crowns.