• IN A NUTSHELL

YOUR BRIEF EXPLAINER TO HISTORY’S HOT TOPICS

The 1918 Sedition Act

The United States’ entry into World War I triggered a wave of frenzied patriotism across the country. However, as Danny Bird reveals, this hysteria set the nation on a collision course with its most cherished principles

What was the 1918 Sedition Act?

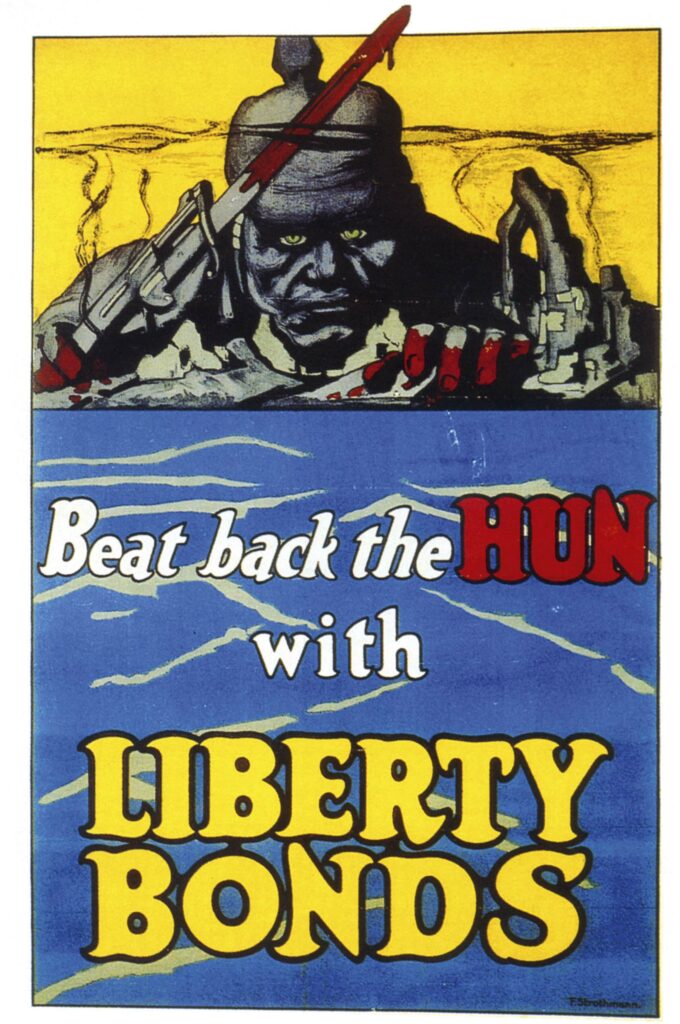

On 16 May 1918, President Woodrow Wilson of the United States signed a piece of federal legislation into law. In fact, this ‘Sedition Act’ was an amendment to the Espionage Act passed by the US Congress 11 months earlier. Despite years of efforts to maintain the country’s neutrality while World War I consumed Europe, America had finally entered the conflict in April 1917. Within weeks, any outlet that cast the US war effort in a negative light, and anything that undermined the government’s sale of ‘liberty bonds’ – debt securities used to fund the Allied cause – was criminalised.

The subsequent Sedition Act expressly persecuted “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” directed against the government, the national flag and mass conscription (the draft) during wartime. Throughout its enforcement, more than 2,000 Americans were arrested, with some fined upwards of $10,000 and others sentenced to 20 years in prison. Wilson’s administration, conscious of the public appetite for keeping America out of the war, as well as political opposition from pacifists, anarchists and socialists, fast-tracked the legislation amid a climate of hysteria.

Why was it passed?

To rally the public behind the war effort, Wilson established the Committee on Public Information (CPI) and appointed a public relations guru, George Creel, to head it up. Finding the word ‘propaganda’ distasteful, Creel instead regarded his brief as akin to advertising – selling a positive angle on the conflict to Americans. Meanwhile, the government, in collaboration with legislators on Capitol Hill and the era’s leading newspaper magnates, mounted a concerted effort to get the Sedition Act passed by Congress. As time went on, the president and his supporters resorted to increasingly extreme and crude ends. Wilson, for instance, openly railed against disloyalty in his speeches and even declared that those out of step with the war effort had “sacrificed their right to civil liberties”. Nevertheless, the congressional debate was fierce, with Republican senators putting up the most resistance. Many expressed concern that it undermined the First Amendment to the US Constitution, which guarantees freedom of speech. It was ultimately passed, however, with the Socialist representative from New York’s 12th District – Meyer London – being a notable dissenting voice.

What did the act prohibit?

The act was designed to suppress ‘disloyalty’ to the United States while it was engaged in war, imposing strict limits on speech and writing that were critical of the government, the constitution, the military or the US flag. Everything from labour strikes that might “cripple or hinder the United States in the prosecution of the war” to expressing support for enemy nations were also forbidden. In addition, it empowered the US postmaster general, Albert Sidney Burleson, to intercept mail believed to violate the act’s provisions.

Who did the act target?

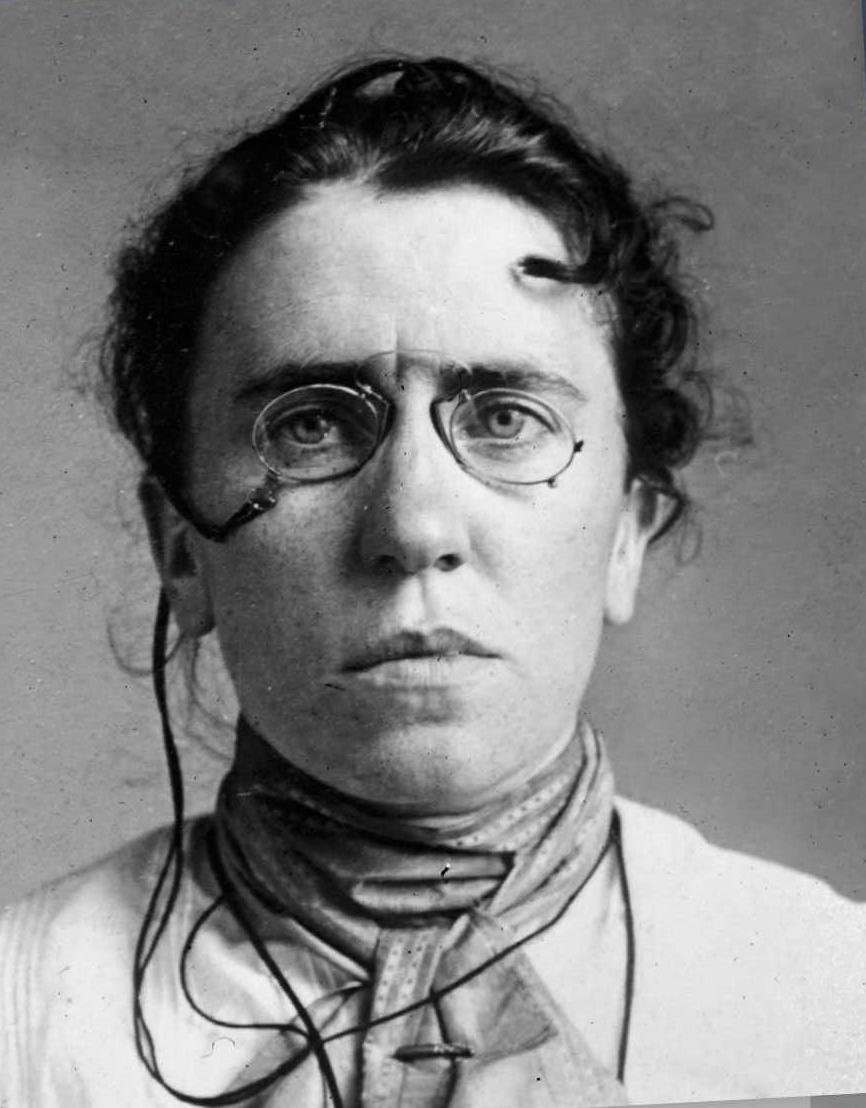

Burleson gladly executed the act’s dictates. As a result, the circulation of suspect letters, pamphlets and radical periodicals like Mother Earth (edited by the anarchist activist Emma Goldman) were severely disrupted by the postal service’s new powers.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court – obliged to uphold the constitution – circumvented the First Amendment. In the landmark case Schenck v United States, Charles Schenck’s criminal prosecution for distributing leaflets that encouraged Americans to resist the draft was defended by the court on the basis that speech could be suppressed if it posed a “clear and present danger”.

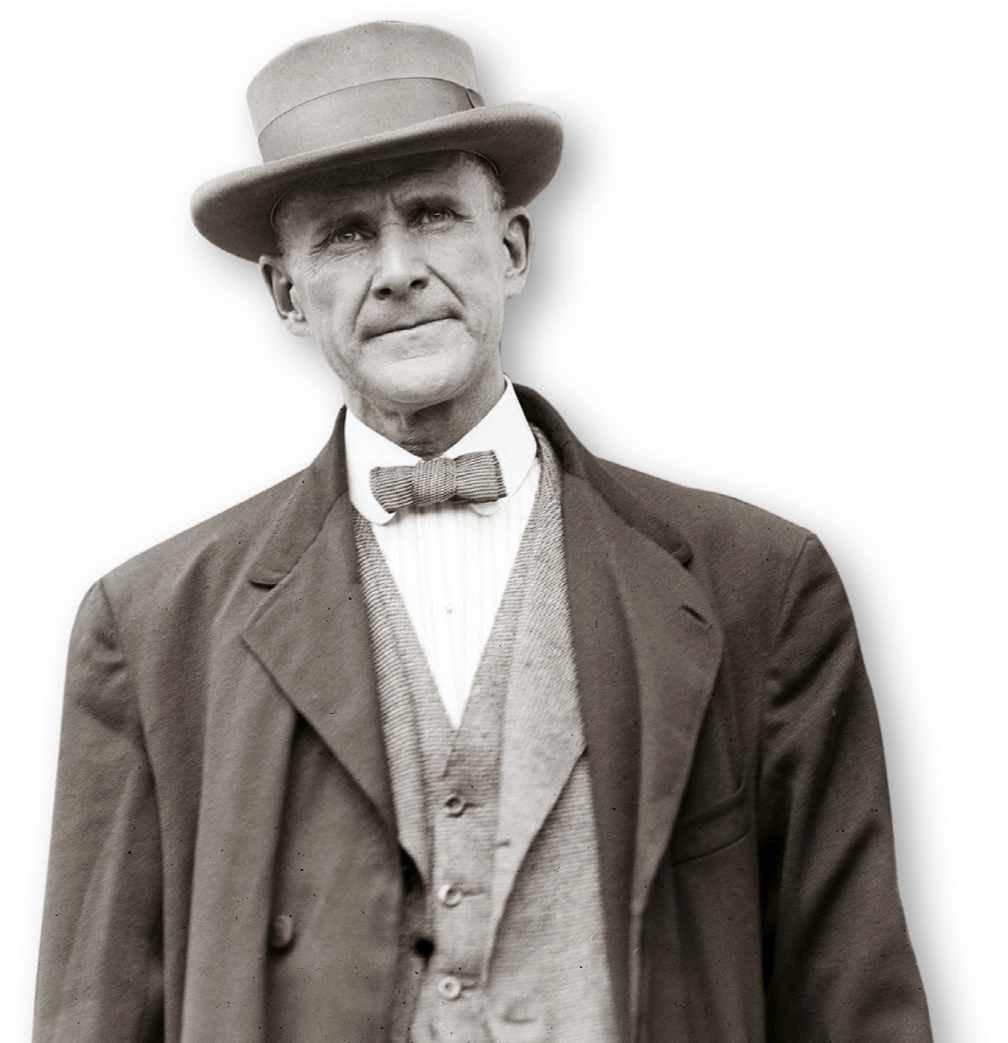

Also chief among the act’s targets were members of the Industrial Workers of the World trade union – the so-called ‘Wobblies’ – with one of its founders, Eugene V Debs, falling foul of its provisions. Debs, an unrepentant critic of mass conscription to the armed forces, was found guilty of breaching the act and sentenced to spend 10 years in jail. His conviction was later commuted by Wilson’s successor, President Warren G Harding, and he was released in 1921.

The patriotic fervour whipped up by the act also had wider effects across US society, encouraging some citizens to adopt a mob mentality. People with German heritage were attacked in the street; vigilantes forced naysayers to kiss the US flag in public; and those who refused to buy liberty bonds sometimes woke up to discover their front doors had been smeared with paint. And nor were religious institutions safe: pacifist congregations sometimes had their churches set ablaze.

However, the Sedition Act came into force barely six months before World War I ended, and – being an amendment to the earlier Espionage Act – prosecutions were few and far between. Weeks before Armistice Day in November 1918, Thomas Watt Gregory, the US attorney general, ordered lawyers across America to seek his approval before proceeding with cases. Wilson unrolled a tentative amnesty in March 1919, releasing or reducing the sentences of about 200 convicts.

With the cessation of hostilities in late 1918, the legislation became null and void and it was repealed on 13 December 1920.

“Those who refused to buy liberty bonds sometimes woke up to find their front doors had been smeared with paint”

What is the legacy of the 1918 Sedition Act today?

The Sedition Act proved that everyday freedoms could be quickly sacrificed in the name of national security. Yet the prospect of a presidential election in 1920 persuaded a Democratic Party hopeful, A Mitchell Palmer, to outline plans for a peacetime repurposing of the act. Despite his claims that there was a radical conspiracy to provoke African-American communities into unrest, Palmer’s proposal was swiftly denounced by his opponents, with publications such as the Christian Science Monitor labelling it “an excess of suppression”.

Despite the repeal of the Sedition Act, the original Espionage Act remained on the US statute book. Decades later, in 1964, the Supreme Court ruled that criticism of public officials by the press was protected under the First Amendment providing it was based on fact.

Today, the crime of seditious conspiracy remains a serious offence in the US and is defined as the conspiracy by two or more individuals to “overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force” the government of the United States.

READ

Historian and author Terrence J Finnegan reveals seven key facts about America’s involvement in World War I on the HistoryExtra website: historyextra.com/america-ww1