CASTLE LIFE

Life within the walls

Medieval castles were hives of activity, filled with servants, soldiers and social climbers

Despite their defensive function, castles in the Middle Ages were also homes and hubs for local enterprise. The size and importance of a castle reflected the scale of its domestic life. They functioned as engines for the feudal economy, with their owners presiding over the management of local rural affairs. During peacetime, they were home to small garrisons of knights, men at arms and archers. But there were also grooms, watchmen, porters, cooks and blacksmiths. The castle’s combatant population would increase whenever conflict threatened to break out. Dover Castle’s proximity to France, for instance, meant that it was regularly supplied with knights by local barons.

The feudal social order was built into a castle’s architecture, with the king, or a lord and lady, cosseted within the most secure parts. While in residence, the nobles resided in comfortable apartments that typically included a busy receiving chamber for visitors, and a private chapel. Although medieval England was a profoundly patriarchal society, noble women could obtain a degree of influence nce within castles.

The political significance vested in aristocratic marriages and producing heirs meant that the lady commandedd a great deal of respect within the social hierarchy, acting as the head of the household. Whenever her husband was away on military campaign or circulating among their other residences, she would be entrusted to oversee the castle’s management, as demonstrated by the likes of Joan de Valence at Goodrich Castle, Herefordshire, during the 13th century.

Not all fun and games

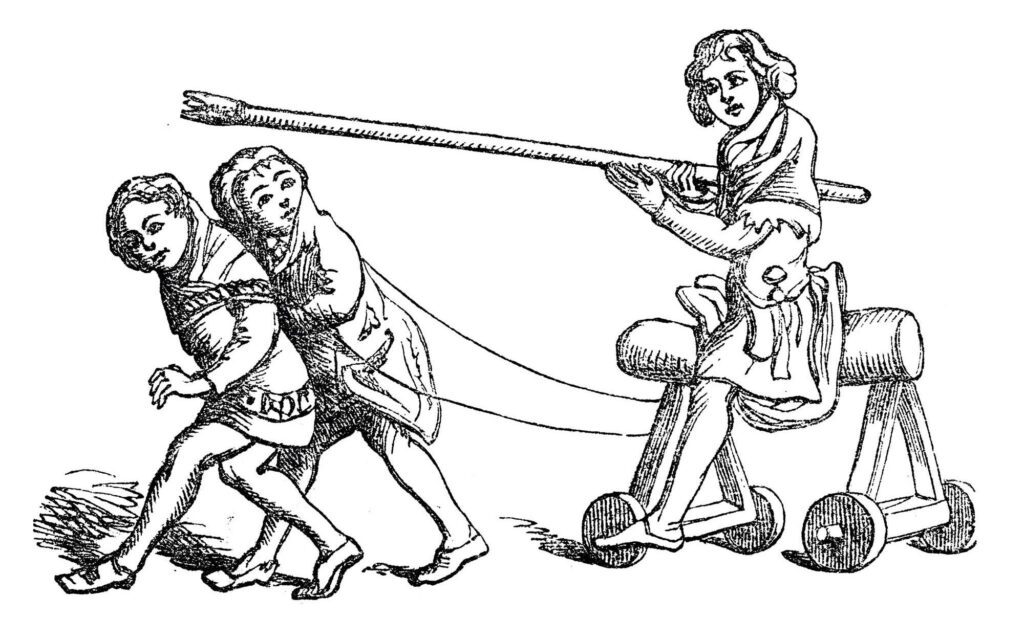

Evidence of children’s toys, from spinning tops, dolls and balls to mock bows and arrows, prove that castles weren’t only home to adults. Noble boys were trained in archery and learned to fence as they reached maturity. Moreover, the children of wealthy families were often employed as pages and damsels and schooled in good manners before attending to the lord’s family.

Larger castles could employ upwards of 50 domestic staff, who were overseen by a steward. He managed all financial and legal matters relating to the castle’s estates – keeping a close eye on rents, or fines issued by the lord’s court. By the 12th century, aristocratic households also included lots of clerks, literate in both Latin and French, to deal with such administrative matters, and also to perform religious services, educate the lord’s children and distribute alms to the poor.

Servants tended to the needs of grander residents, ensuring the castle’s daily life functioned without a hitch. Though their employment was often a drudgery – everything from turning the spit over an oppressively hot kitchen fire to mucking out the castle’s stables – the life of a servant was far preferable to that of a peasant. Dressed in colourful liveries (uniforms) that denoted their lord’s heraldry and working long hours for little pay, servants could at least look forward to regular meals and a relatively comfortable place to rest their heads at night, which could be literally anywhere within the castle.

Doing the dirty work

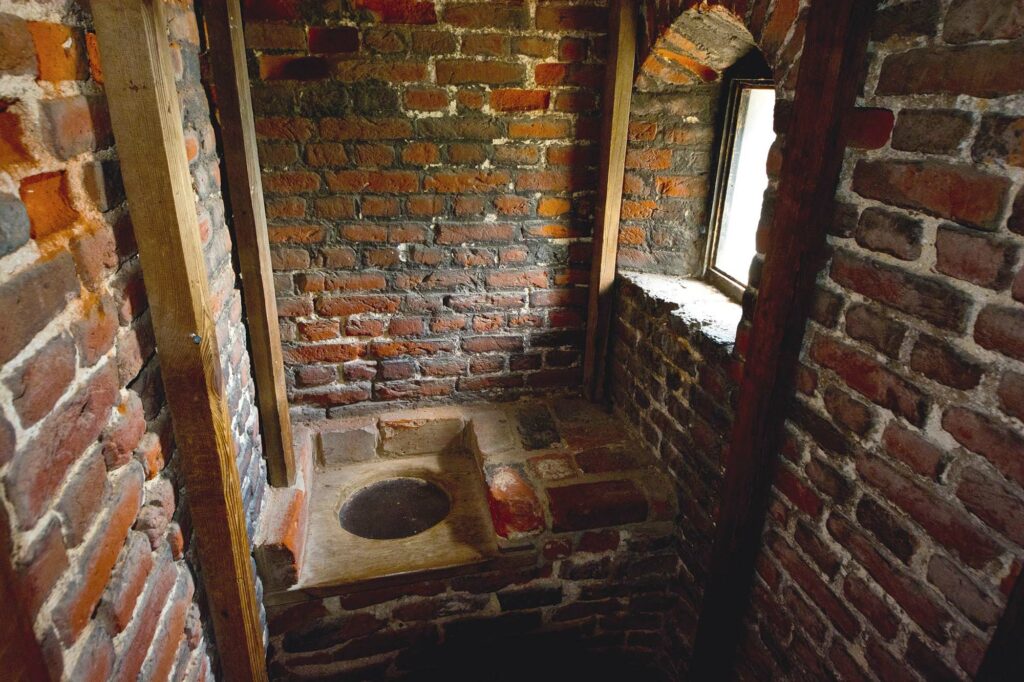

Garderobes – toilets made from planks of wood with holes in them – were almost always situated along a castle’s northern wall. They would overhang a moat or ditch, into which human waste would drop and accumulate. Lords’ chambers often contained their own privy, while some castles, like Goodrich, hosted more communal amenities. One of the best-paid employees in a castle was the so-called gong farmer, the individual whose task it was to clear out the cesspit. As well as being extremely unpleasant, this was a dangerous profession, as a man known only as ‘Richard the Raker’ found out in 1325 after falling into one and drowning.

“Entertainment was a key component of everyday castle life and revolved around mealtimes”

Although castles must have been largely cold and damp places, particularly in winter, most of their communal spaces featured large open fires. Every castle boasted a great hall, which acted as the focal point for all significant occasions – especially feasting and revelry. Often these were heated by a roaring hearth in the centre of the room, with a louvre in the roof above to allow the smoke to escape. Tapestries hung along the walls would have also provided some moderate insulation from the elements. Entertainment was a key component of everyday castle life and revolved around mealtimes. An early lunch might encompass as many as 10 courses, followed by dancing and music from troubadours and minstrels. Epic poetry, regaling the lord and his entourage with tales of romantic derring-do, dramatic play-acting and slapstick courtesy of a jester, were all popular pursuits. Knights could hone their martial skills in tournaments, and hunting parties stalked prey across the castle’s estate.

Religious festivals were also major fixtures in the castle’s annual calendar and would often result in the number of its inhabitants swelling at certain points in the year. At Christmas, seasonal foliage such as holly and ivy would adorn the interiors, while a Yule log would burn in the great hall. The lord would treat his knights to festive hospitality, while the domestic staff celebrated with a largesse of food, drink and clothing.