• THIS MONTH IN… 1768

ANNIVERSARIES THAT HAVE MADE HISTORY

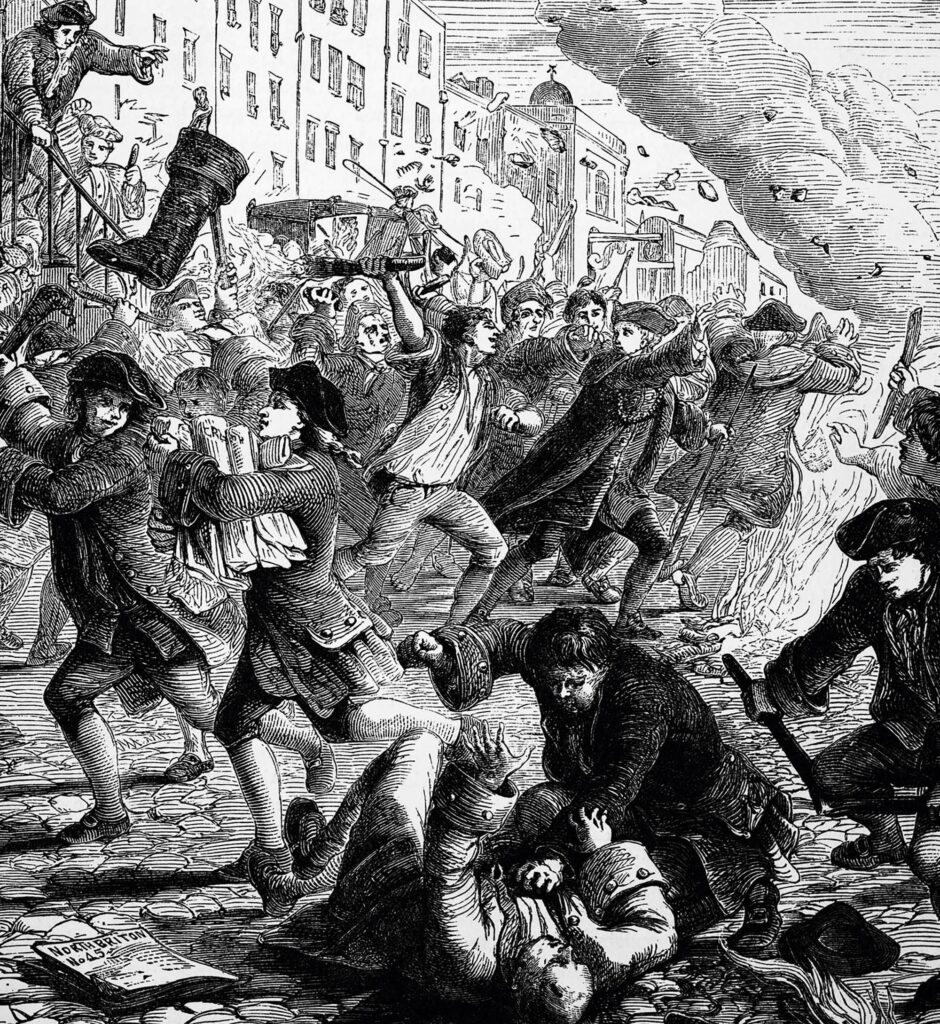

Deadly riots break out in London

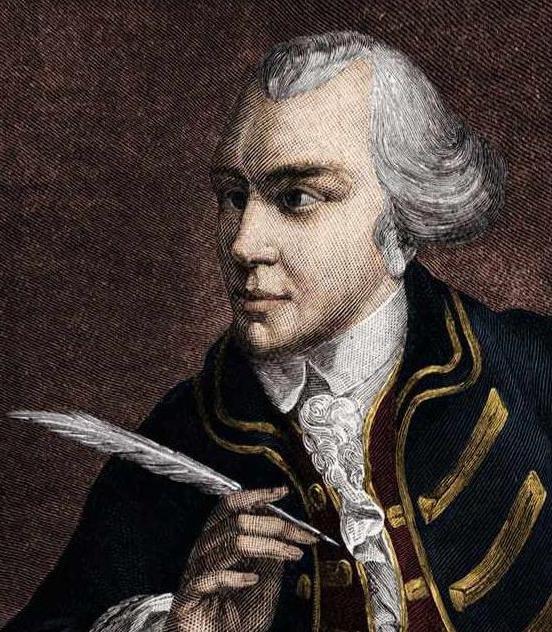

The radical MP John Wilkes attracted loyal support for his outspoken criticism of the government. However, as Danny Bird explains, outrage at his 1768 arrest for libel paved the way for bloodshed and anarchy

On 10 May 1768, a crowd of about 15,000 people gathered on St George’s Fields in Southwark, south London. The focus of their protest was the adjacent King’s Bench Prison, where their champion, the radical MP John Wilkes, had recently been incarcerated for seditious libel.

As tensions escalated, magistrates appealed for armed support. Before long, word of a man’s murder by soldiers inflamed the febrile situation. When the Riot Act was read out, projectiles rained down on the troops, prompting them to fire at the crowd. Panic surged across the large open space, the multitude dispersed, and riots erupted all over London.

Rabble-rousing

Six years prior, Wilkes had founded a satirical newspaper, The North Briton. Its editorial line was particularly scathing of the Earl of Bute, the prime minister and mentor to the young George III. The conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763 led to the king hailing the peace terms before the House of Lords – something Wilkes deemed outrageous. Days later, The North Briton’s 45th issue denounced the king’s address and attacked his ministers for encouraging him to accept the Treaty of Paris’ “most odious measures”.

The issue number was opportune, recalling the year of the last Jacobite rising (1745) against the reigning Hanoverian dynasty. It also fuelled rumours of Bute’s alleged Jacobitism (support for the deposed James II and his heirs, whose strongest support had come from Catholic clans in the Highlands) because of his Scottish heritage. Conversely, however, it presented Wilkes’ enemies with an opportunity to silence him. George III, already flustered by The North Briton’s scurrilous innuendos about Bute’s rumoured affair with his mother, Princess Augusta, issued a general warrant for Wilkes’ arrest on a charge of seditious libel.

Radical elements within British society, notably the London mob, rallied to Wilkes. After rebuking general warrants as an affront to England’s “ancient freedoms”, Wilkes was released when a judge ruled that parliamentary privilege (legal immunity for members of both houses of Parliament) absolved him from prosecution. His supporters lauded the outcome, adopting the slogan “Wilkes and Liberty!”, and he reprinted the issue along with a lewd parody of Alexander Pope’s famous poem An Essay on Man.

But this time, his adversaries doubled down. The poem was condemned as “scandalous, obscene and impious libel” in the Lords, while the Commons voted to proscribe issue 45 as seditious libel, asserting that parliamentarians could not be exempted from such a charge. Wilkes escaped to Paris and was tried in absentia. He was found guilty and declared an outlaw.

“The crowd’s mood soured and some began hurling stones at the troops, who primed their weapons”

Urban unrest

After deciding to return to Britain in 1768, Wilkes stood for the Middlesex constituency against the government. But despite winning the seat, the radical MP turned himself in and was imprisoned in April. Over the coming weeks, legions of so-called ‘Wilkites’ assembled on St George’s Fields to protest against his imprisonment, and by 10 May, the number of protesters had swollen to several thousand. One commentator described them as an “unarmed giddy mob”, as chants of “Damn the king, damn the government, damn the justices!” reverberated. Fearing the crowd would overwhelm the prison and free Wilkes, magistrates ordered a detachment of Horse Grenadier Guards to repel them from its immediate vicinity.

It didn’t go to plan. Amid the chaos, three soldiers from the Scots Guards pursued a particularly provocative protester into a cowhouse next to the Horseshoe Inn, along the fields’ eastern flank. Upon entering, an officer fired his musket at the wrong individual, killing the landlord’s son, William Allen. Thereafter the crowd’s mood soured, and some began hurling stones at the troops, who primed their weapons. There was a crackle of gunfire, resulting in six or seven deaths, while a further 15 people were injured.

After the shootings, the protesters dispersed, carrying Allen’s body across London Bridge and into the City. However, the trouble was far from over. Before long, further crowds had massed outside the Mansion House and Parliament, and riots had broken out in Limehouse and Spitalfields. Benjamin Franklin – the future founding father of the United States, who was resident in London at the time – witnessed scenes akin to civil war: “This capital… is now a daily scene of lawless riot and confusion. Mobs patrolling the streets at noonday… soldiers firing among the mobs and killing men, women, and children…”

So acute was the crisis that George III even contemplated abdicating. Of course, he never did. The disorder subsided, and while William Allen’s father fought a long legal battle to prosecute two soldiers he believed were responsible for his son’s death, the matter was dismissed. As for John Wilkes, he would go on to be released from prison in 1770, before being elected Lord Mayor of London and re-elected as the MP for Middlesex in 1774. While his radicalism softened later in life, his name would forever be associated with the tragedy on that May day in 1768.

DID YOU KNOW?

NUMBER OF LIBERTY

Radicals on both sides of the Atlantic embraced the number 45 following the controversy of The North Briton’s most notorious issue. One preacher even highlighted Psalm 119’s 45th verse: “I will walk in Liberty, for I keep thy precepts”.

OTHER ANNIVERSARIES

A look back at other events that have taken place in May throughout history

7 May 558 AD

The Hagia Sophia’s dome collapses

Already damaged by two previous earthquakes in 553 AD and 557 AD, the dome of Constantinople’s (modern-day Istanbul) mighty basilica finally succumbs to total structural failure after another tremor. The Byzantine emperor Justinian I entrusts Isidorus the Younger with the dome’s reconstruction, which he achieves by incorporating an innovative system of load-distributing supports. The building is reopened just four years later.

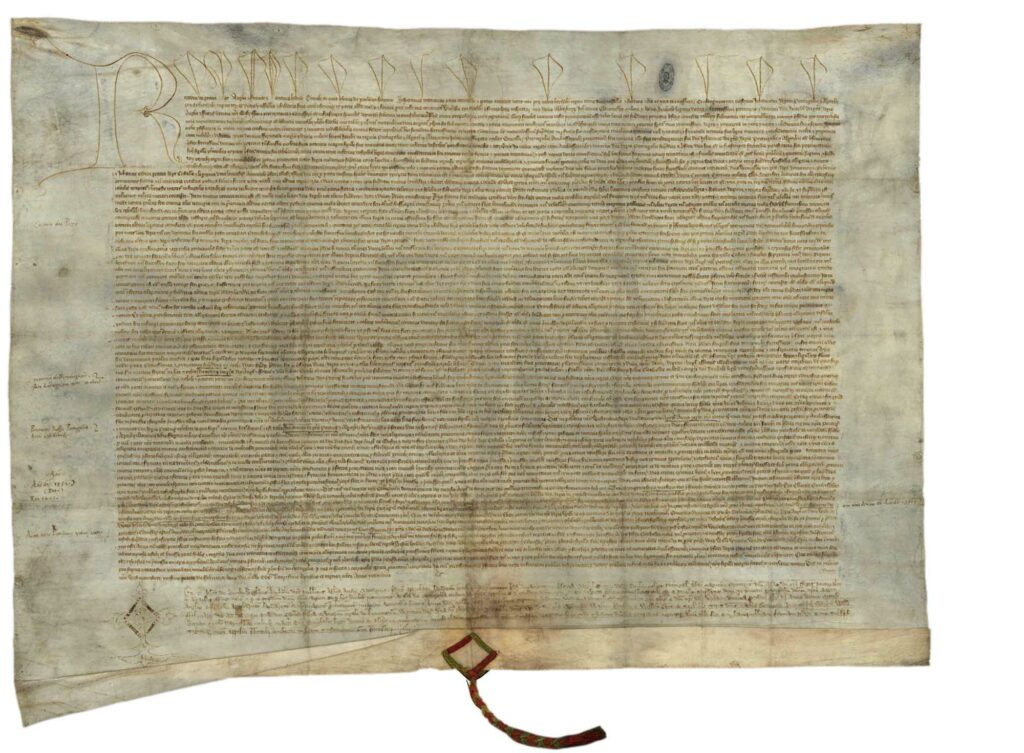

9 May 1386

Portugal and England sign a lasting truce

The kingdoms of England and Portugal sign the Treaty of Windsor (pictured), sealing a diplomatic alliance that culminates in the marriage of Philippa of Lancaster to King John I of Portugal – a union celebrated with the exchange of wine, salt, oil and other exotic items between the two realms. Enduring to this day, the Treaty of Windsor holds the record for the longest-lasting diplomatic treaty in recorded history.

28 May 1871

Troops suppress the Paris Commune

Paris lies in ruins after a week of brutal street fighting between supporters of the two-month-old Paris Commune and French troops. Indiscriminate shelling by government forces and arson leaves many landmarks gutted, while hundreds of people are summarily executed in public spaces. Thousands more are marched on foot to open-air prison camps in Versailles.