HISTORY OF ART

Save Willie McGee

Alice Neel’s bold, unapologetic works bared the souls of men, women and children living on the fringes of society

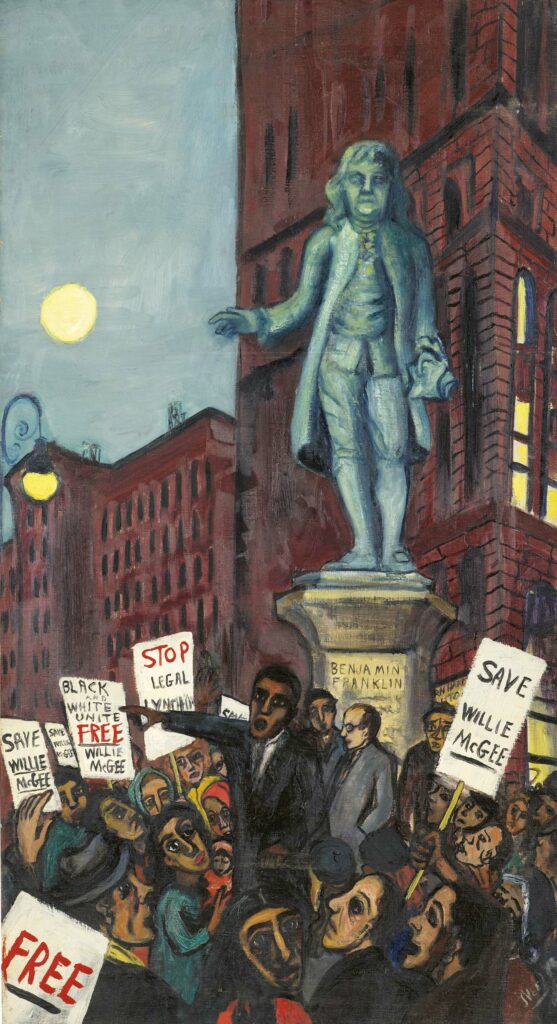

Save Willie McGee

by Alice Neel, c1950

In November 1945, Willie McGee, a young black grocery truck driver from Mississippi, was arrested on charges of raping a white woman. Between 1945 and 1951, McGee saw three circuit-court trials, several reversals and four failed attempts at a full review by the US Supreme Court before his eventual execution in May 1951, at the age of 35.

The case captured both national and international interest, with many campaigning for McGee’s release, believing him to be an innocent victim of both racial prejudice and refusals by those in the Jim Crow South (the name given to the predominantly Southern system of racial segregation in the US) to accept an interracial extramarital affair. More than 10,000 letters were sent to President Truman demanding freedom for McGee, and several high-profile names, including Albert Einstein, Josephine Baker and William Faulkner, joined the calls for clemency. Another voice passionately proclaiming McGee’s innocence belonged to Alice Neel, an artist living in New York’s Spanish Harlem.

“Neel was a committed political artist who used her paintings as a way of speaking out,” says Eleanor Nairne, curator of a new exhibition on Alice Neel at the Barbican Art Gallery in London. “She had joined the Communist Party in the early 1930s, and since McGee’s defence was paid for and managed by the Civil Rights Congress [the New Yorkbased civil rights arm of the Communist Party USA], Neel would have been aware of, and even involved in, the creation of flyers and the campaigning around this case. More than 20 years later, in 1970, she actually painted Bella Abzug, the lead counsel for Willie McGee.

“Neel was someone who regularly attended pickets and rallies,” continues Nairne, “and we know she was present at the protest depicted in this work. One of her earlier paintings, Magistrates Court (The Courtroom Scene) was created from her own memory of being arrested following a protest.”

Voice of the underground

Neel had moved to New York after the collapse of her marriage to Cuban artist Carlos Enríquez, and her nervous breakdown and subsequent hospitalisation that had followed the death of their 11-month-old daughter. Enríquez took their second daughter to live with his family in Havana, and Neel moved to Greenwich Village where she became “court painter of the underground”, devoting herself to creating candid, sometimes shocking, portraits of individuals not often captured on canvas – from queer couples and pregnant women, to local children and black intellectuals.

In 1933, with the Great Depression casting its pall over American life, Roosevelt launched his New Deal programme – aset of domestic policies designed to counter poverty and unemployment. The programme included the Public Works of Art Project and, later, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA); Neel signed up to both and received a weekly wage of $26.88, submitting a painting every six weeks in return. For the first time in US history, painting was recognised as wage-earning labour and, as part of her work with the WPA, Neel began painting street scenes, recording adversity in the city in her own unique style.

“This was a time of racial segregation in the US; an era when homosexuality was illegal and prosecutable,” concludes Nairne. “But Neel believed in people. She believed that everyone had an equal right to live well, and she felt that this right was being violated. Her decision to paint the men, women and children she chose to paint was very much against the tide.”

“One of the reasons I painted was to catch life as it goes by,” explained Neel in later life, “right hot off the griddle… the vitality is taken out of real living.”

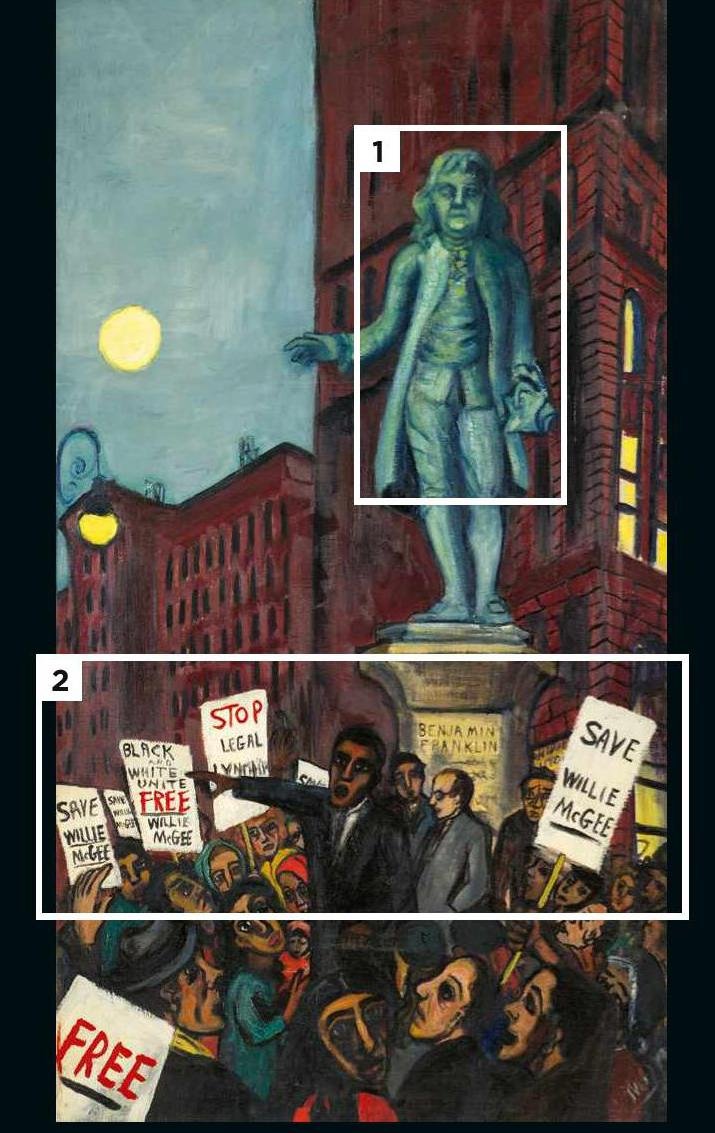

1. STATUE

The statue of Founding Father Benjamin Franklin depicted here still stands across from New York’s City Hall. New York was one of many cities across the US that saw organised mass demonstrations in support of Willie McGee.

2. PLACARDS

An arc of white placards with bold red writing call for McGee’s release. Despite protests like this, McGee was executed on 8 May 1951. In a last note to his wife, written the night before his death, he told her: “Tell the people to keep on fighting.”

VISIT

Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle – featuring Save Willie McGee – is on show at the Barbican Art Gallery in London until 21 May 2023. See the gallery website for more information and details of how to visit: barbican.org.uk