BRITISH CASTLES Q&A

Everything you wanted to know about British castles

Dr Marc Morris answers questions about the origins of the structures and their development over the centuries

Q: How would you define a castle?

A: Well, the dictionary definition of a castle is fairly limited, describing them as fortresses or strongholds. Now, of course, the primary function of many castles was defence. But they also had to be domestic, a combination of aristocratic residence and fortification. So that’s the working definition of a castle, if you like. In more recent decades, more nuanced academic interpretation has argued that not all castles were defensive. Some castles, particularly towards the end of the Middle Ages, were built more for show than for practical, defensive purposes. So the definition then becomes a bit problematic. I subscribe to the idea that if it was called a castle at the time, then it’s probably a castle.

I think you can start to be dismissive of castles if they are Iron Age hillforts, such as Maiden Castle in Dorset, or 19th-century baronial pads. They might look good, but I wouldn’t add them to my big book of castles. In essence, a castle can broadly be defined as a residential fortress or a fortified residence.

“In essence, a castle can broadly be defined as a residential fortress or a fortified residence”

Q: When do we first see castles in Britain?

A: I tend to go with the traditional argument, which is that castles came to England with the Norman Conquest, in 1066. It’s a little bit more nuanced than that, of course, in that there are a handful of castles that pre-date the Conquest by 15–20 years. In fact, it’s actually useful to take this question back a step and look at when we first see castles in Europe. As I’ve said, there is a very strong argument that castles were introduced in a tidal wave from 1066, but they were quite novel in western Europe as a whole. It’s hard to precisely identify their origins, but in c1000, in western Francia (what later becomes France), you would find castles being built along the Loire Valley and in Normandy. New principalities were emerging at this time and they were becoming very powerful, with wealthy people able to carve out little lordships for themselves. And their weapon of choice was the castle. And what differentiates castles, by my definition, from what came before is that these were private, and they were smaller than old-school fortifications.

Compared with early fortifications – Iron Age hillforts, Roman forts, or indeed the burhs of Anglo-Saxon England [large communal fortifications that covered many acres of land], castles were considerably smaller, and they were built for a lord and his household. So castles were only two or three generations old when the Normans famously invaded England in 1066, and they seemed to come as a big shock to the Anglo-Saxons. There had been one or two castles built in England in the 1050s by French friends of Edward the Confessor, but after 1066 there was a deluge of castle building, something that is lamented by contemporary English chroniclers.

Q: What types of castles were being built after 1066?

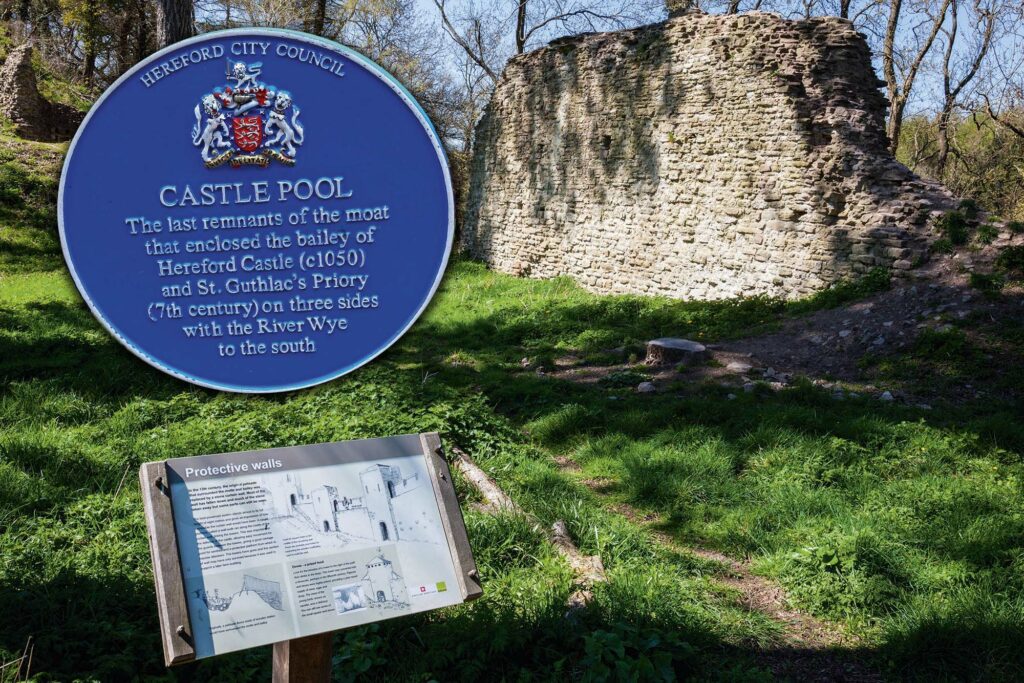

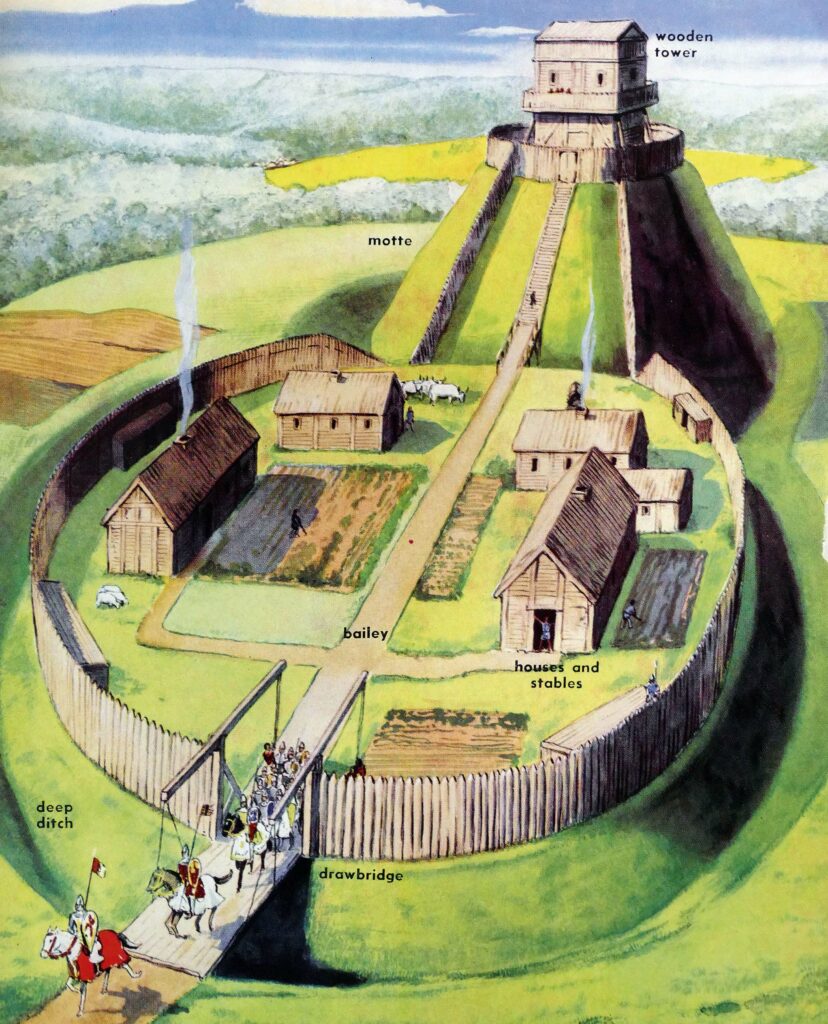

A: Castles developed and changed across the centuries, but those introduced by the Normans were mostly motte-and-bailey structures. The motte was a great artificial mound of earth on which a wooden (later stone) tower was built. A lower, shallower enclosure called the bailey was defended with ditches and wooden palisades, in which everything besides the tower could be found – stables, chapel, great hall, and so on. Motte and baileys made up about 75–80 per cent of the castles built in the two or three generations after the Norman conquest.

Going forwards, all sorts of structural variations were introduced, such as great stone towers. Building began in timber, and then, depending on resources, those wooden buildings would be converted to stone. Most castles remained earth and timber until a lord decided to invest in one or two specific locations, places they really wanted to awe and entertain people. And that’s where they would start to rebuild in stone and when you get places like the Tower of London.

In later centuries, you get things like twin-towered gatehouses, and a shift from great towers to curtain walls (defensive walls between two towers or bastions).

Q: Why were so many castles built in Wales?

A: The principle reason, I would say, was geography. England is – with some exceptions – mostly low-lying land, with rivers and open plains. Once you get into Wales, of course, the landscape is much more hilly and mountainous, with fasterflowing rivers – territory that was much more difficult to control. And it was also land outside of England.

Medieval England was a precociously advanced and centralised state and had a form of royal governance that was much more intrusive and invasive than anything in Wales, which had a host of competing rulers who were also building their own castles in order to secure their territories.

And, of course, Wales takes a long time to be conquered. It wasn’t until more than 200 years after the Conquest that Edward I finally conquered north Wales with his string of majestic fortresses, like Conwy, Caernarfon, Harlech and Beaumaris.

Q: Did the Crusades influence castle-building in England?

A: A century or so ago, it was taken as read that the Crusades influenced western architecture. It was believed that western knights went to the Middle East, saw wonderful, more advanced structures, came home and started customising their own castles accordingly. The problem with this theory is, as people have pointed out over the last 50 years or so, is that it’s very hard to point to actual examples of architectural borrowing. For example, we could attribute round towers to Middle Eastern influence, but there were actually plenty of round towers in England before the Crusades, evidenced in Roman forts from 800 years earlier. I don’t think there’s a physical example we can point to as a clear example of architectural borrowing.

The one interesting exception to that rule is the word ‘barbican’, which is a term used to describe a gate outside the main gate. The word is thought to derive from the Persian or Arabic word bab-khanah, meaning gatehouse. We start to see barbicans being talked about in the west in around 1200; the origins of the word suggest that people had seen these exterior gates, which stopped people accessing the main gate, during time spent in the east, and brought the idea back home.

Q: What would daily life have been like inside medieval castles?

A: As I’ve already mentioned, it’s important to remember that castles weren’t just built for defence; they were residential as well. The shells of the castles we visit today are a far cry from how they would have looked in their heyday.

There might have a been a well running up through the centre, which would have provided running water inside the building, while rainwater from a tank on the roof could have been piped into rooms below. Initially, toilets and general creature comforts were a rarity, although there are toilets in the Tower of London that date from the late 11th century. By the late medieval period, however, most castles would have boasted a fireplace in every room, a window with a window seat where you could sit and embroider or read, and a door leading to a privy space with a toilet.

If you were a lesser member of the household, even in a royal household, you wouldn’t have had your own room, and would have found a bit of floor on which to bed down for the night. But by the 13th and 14th centuries, senior servants would have expected to have their own rooms and a bed to sleep in.

“The shells of the castles we visit today are a far cry from how they would have looked in their heyday”

Q: How were castle interiors decorated?

A: Again, the key word here is luxury. Castles were built by, and for, the richest people in society, people who were used to the finer things in life. Internal walls would have been plastered and then whitewashed – there was no bare masonry on show – and hung with tapestries. The fashion in the 12th and 13th centuries was to trace or paint red lines on the whitewashed walls in a type of brickwork pattern, as if it were made from large blocks of stone. You can still see traces of this design in the upper floors of Marten’s Tower at Chepstow Castle in Wales.

Something that might surprise readers is the colour palette used. Bright colours aren’t always associated with the Middle Ages, but castles would have been decorated with bright blues, reds and greens. About 14 years ago, English Heritage redecorated the Great Tower of Dover Castle with colours that would have been used when it was first built, in the reign of Henry II – it’s probably the best modern approximation of how vivid medieval castle decor could be.

Dr Marc Morris is the author of several critically acclaimed books on medieval history, including Castle: A History of the Buildings that Shaped Medieval Britain (Windmill, 2012)

LISTEN

You can listen to a full version of this interview on the HistoryExtra podcast, available to stream at historyextra.com/podcast