SIEGE TACTICS

How to capture a castle

Dr Marc Morris reveals his top tips for prosecuting a successful medieval or early modern siege

Surround the castle effectively

This sounds obvious, but in practice it is very difficult to achieve. The surest way to get a garrison to surrender is to starve them into submission, which means ensuring that they can’t get any extra supplies of food. Creating an impenetrable ring around a castle, however, presents a considerable challenge. In order to stay safe themselves, the besiegers need to remain beyond the range of the bows or guns of the defenders, so they cannot encircle the castle too tightly. The perimeter of their lines might therefore run for a mile or more, which is a lot of ground to cover, even if you have sufficient troops to do so. It becomes even more difficult at night, when the garrison might try to sneak supplies into the castle under cover of darkness.

When Oliver Cromwell arrived to take over the siege of Pontefract Castle in 1648, he discovered that its royalist garrison were abundantly supplied thanks to the negligence of the previous parliamentarian commander, who had failed to mount an effective blockade. “The castle has been victualled with 240 cattle within these three weeks,” he wrote to his colleagues in London, “and they have also gotten in salt enough for them, so that I apprehend they a victualled for a twelvemonth.”

Try to sneak in

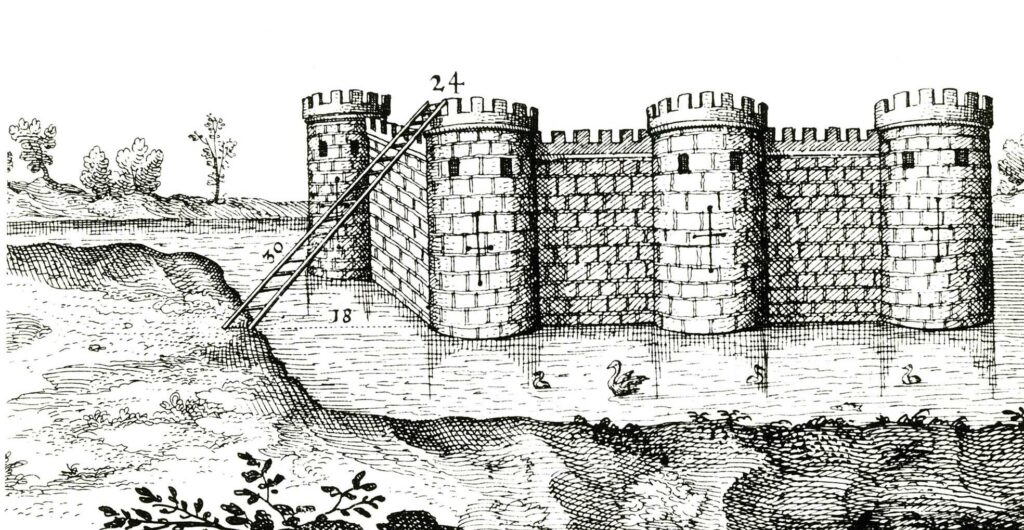

If it’s difficult for the besiegers to maintain constant vigilance, the same goes for the defenders. One of the swiftest ways to bring a siege to a successful conclusion is to sneak inside, taking the garrison by surprise. There are various ways that attackers might attempt to go over a castle’s walls – by using scaling ladders, or ropes with grappling hooks. They might also bring up to the walls a wheeled tower known as a belfry, though that would almost certainly deny them the element of surprise.

Many famous sieges have been ended by acts of cunning on the part of the besiegers. In the case of Pontefract in 1648, the royalists had originally gained control of the castle by posing as delivery men. The parliamentary garrison had ordered more beds from the town, so the royalists simply walked in carrying beds, concealing their weapons in the mattresses. When Château Gaillard, the great fortress in Normandy built by Richard the Lionheart, finally fell to the French in 1204, it was thanks to the daring of a small group of men who edged around the walls and stood on each other’s shoulders in order to reach the window of a new chapel, lately added to the castle by Richard’s brother, King John.

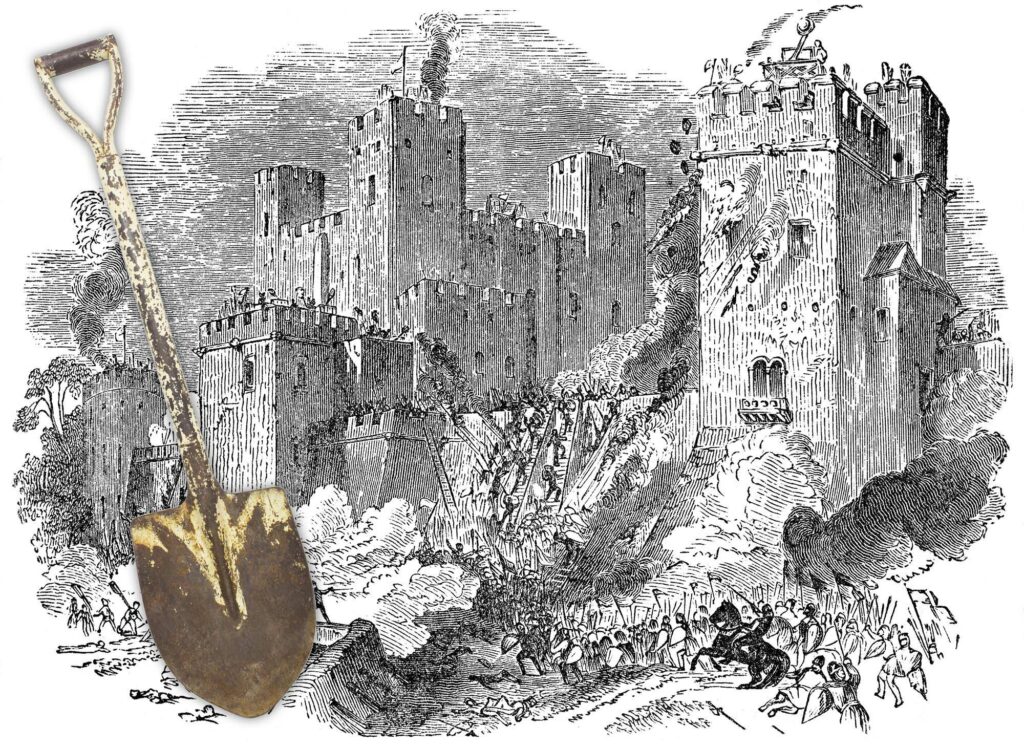

Dig tunnels

If going over the walls isn’t an option, you could always try going under them. The objective in digging a tunnel is not to emerge, rabbit-like, inside the castle, but to remove the foundations of the walls, thus creating a collapse.

There were two famous examples of this technique during the reign of King John, when he was at war with his barons. In the first case, the king himself laid siege to Rochester Castle, and gained victory by undermining its great tower. In a letter written a few days beforehand, John ordered the delivery of 40 pigs, whose fat was used to burn the props that supported the tunnel dug by his miners.

The following year, John’s supporters at Dover Castle found themselves besieged by a French army, led by the future King Louis VIII. The French initially undermined the barbican – a new outer enclosure, with walls made of wood – and then the castle’s main gatehouse, causing one of its stone towers to collapse. At Dover, however, the defenders held out, fighting off the attackers and then repairing the breach with timbers from other buildings within the castle.

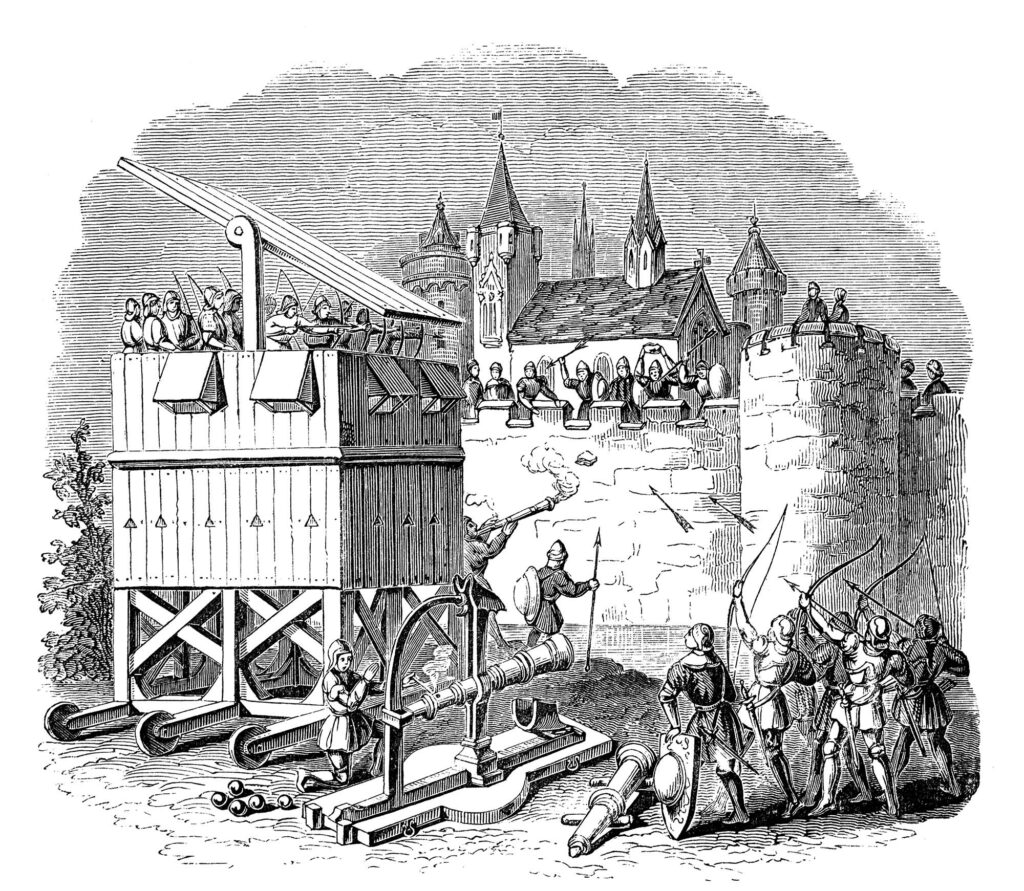

Try to smash in

If tunnelling under the walls is impossible – if, say, the castle stands on solid rock, or is surrounded by a moat – then another option is to go through them. You might try to force your way in through the castle’s entrance, using a battering ram on the doors, but this is likely to be very heavily defended. By the start of the 13th century, gatehouses had multiple sets of doors and portcullises, protected with murder holes in the ceiling above and arrow-loops throughout. The alternative was to try to demolish the walls themselves by using catapults to hurl giant stone projectiles. In the early days, such machines were not terribly effective against stone castles, because they relied on teams of men tugging on ropes.

Around the year 1200, however, a new type of catapult arrived in Europe. The trebuchet, as it was known, was powered by hoisting a heavy counterweight several feet into the air, and then pulling a lever to let it drop. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, besiegers could bombard a castle’s walls even more effectively by using great guns. A mighty surviving example is Mons Meg, cast in 1449 by the Duke of Burgundy as a present for James II of Scotland. The difficulty for besiegers was that such huge weapons took time to construct, in the case of trebuchets, or, in the case of cannon, time to transport – weeks of trundling behind teams of horses or oxen.

Target the defenders

If going over, under, or through the walls proves impossible, a remaining option is to target the people within the castle. Soldiers manning the battlements can be picked off individually by conventional archery or by using crossbows. In later centuries, guns were available, though the earliest examples, being more like blunderbusses, lacked the precision for sniping.

By sending burning arrows into a castle you could try to set light to its wooden buildings, and the same effect could be attempted on a grander scale by throwing flaming projectiles with a trebuchet. An even more insidious ploy would be to hurl the bodies of diseased animals into the castle, in the hope of spreading deadly infection among the defenders.

By far the most terrible anti-personnel weapon in an attacker’s arsenal, however, was the mortar. First used in Britain in the 17th century, mortars were shorter and squatter than conventional cannon, because all they had to do was lob their missiles over the walls and into the residential heart of the castle. The missiles themselves, known as grenadoes, were explosive, and on detonation their metal shards would tear through flesh and bone. Just the sight of mortars being moved into position was enough to terrify those inside. “Little ladies had stomach to digest cannon,” wrote one of the defenders of Lathom House in 1644, “but the stoutest soldiers had no heart for this… the mortar pieces had frightened ’em from meat and sleep.”

Sow false information

The effect of mortars on the defenders’ morale reminds us of the importance of psychological warfare. Very few sieges take place in isolation – they are almost always part of a wider conflict. In most cases, the besiegers will be holding out in the hope of being relieved by some superior force. That being the case, why not send letters or messengers into the castle, telling them that their allies have been defeated in battle, and that all hope of relief is now lost? Assuming you’ve managed to mount an effective blockade, the defenders will have been deprived not only of food but also of news.

In 1271, the garrison of the great crusader castle of Krak des Chevaliers in Syria surrendered to the besieging forces of the Egyptian sultan, Baibars, after receiving a letter from their supreme commander, the Grand Master of the Hospitallers, instructing them to do so. It was, they later discovered, a forgery concocted by none other than Baibars himself.

Dr Marc Morris is the author of several critically acclaimed books on medieval history, including Castle: A History of the Buildings that Shaped Medieval Britain (Windmill, 2012)