HISTORY A–Z

An A–Z of coronations

On the eve of King Charles III’s coronation, Nige Tassell takes us on an alphabetical tour through the history of the royal ritual in all its glory

For in-depth features and podcast episodes about the coronation of King Charles III, visit the HistoryExtra website: historyextra.com

A is for… Archbishop of Canterbury

Almost all English coronations since 1066 have been conducted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the most senior member of the Church of England. While it is arguably the pinnacle of any archbishop’s service, not all have been dutiful and willing to carry out the high-prestige role. In 1689, the then archbishop, William Sancroft, did not officiate at the joint coronation of William III and Mary II as he failed to acknowledge the legitimacy of their ascension to the throne after the removal of Mary’s father, James VII and II, in the Glorious Revolution. The Bishop of London officiated instead.

B is for… balcony appearance

When the pomp of the ceremony has finished, and the coronation procession undertaken back to Buckingham Palace from Westminster Abbey, another aspect of modern coronations takes place: an appearance from the newly crowned monarch on the balcony of the palace. The first such appearance was in 1902 when Edward VII and Queen Alexandra stepped out to receive the acclaim of the crowds gathered down below. Since then, a balcony appearance has been a fixture of post-coronation celebrations, and in 1953 was accompanied by a fly-past of massed planes – something that Edward, his coronation a year before the Wright brothers first took to the skies, wasn’t treated to.

C is for… Cromwell

“I cannot undertake this government with the title of a king, and this is mine answer to this great and weighty business.” In May 1657, Oliver Cromwell – who had signed the death warrant of Charles I eight years earlier – turned down Parliament’s offer of the crown. He was, though, ceremonially reinstalled as lord protector at Westminster Hall one month later. Although he wasn’t crowned, the occasion shared many of the trappings of a coronation: Cromwell wore a purple robe lined with ermine and sat on the Coronation Chair, which had been transported from Westminster Abbey next door.

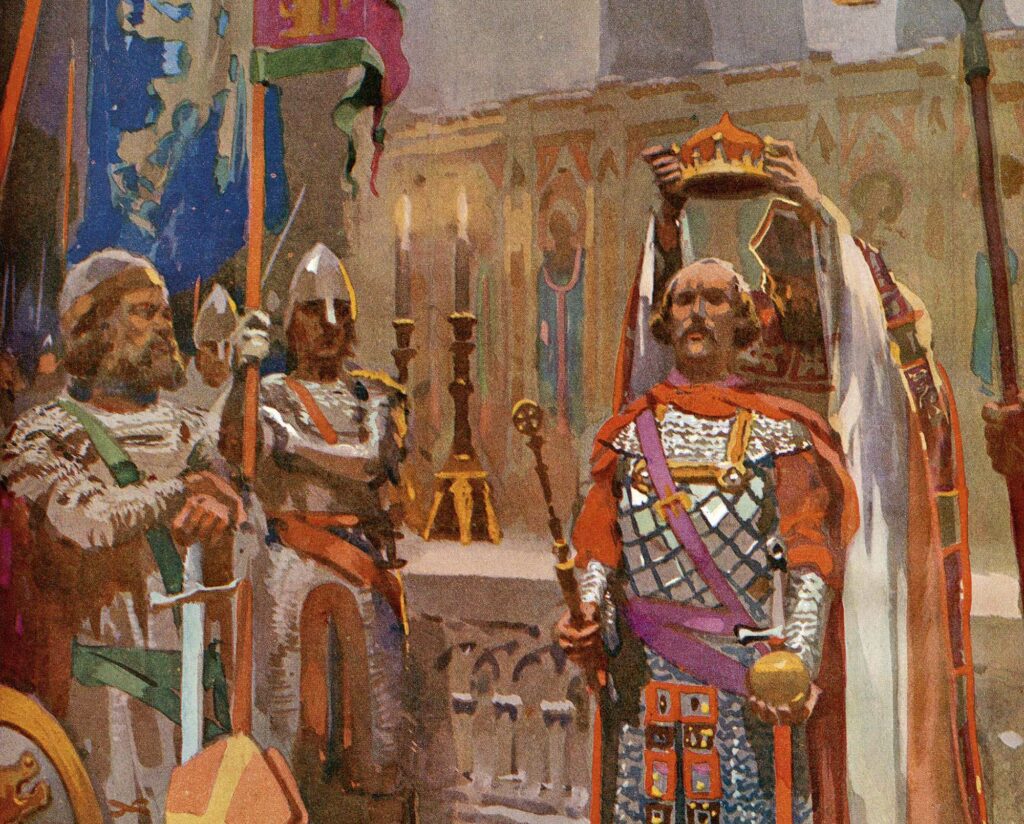

D is for… Dunstan

If there is one chief architect of the coronation ceremony that is still largely used for the crowning of British monarchs today, it is Dunstan, the 10th-century archbishop of Canterbury later canonised as Saint Dunstan. Presiding over the coronation of King Edgar in Bath in 973, he oversaw all aspects of the ceremony. Dunstan’s service emphasised the union between church and monarch, and raised the stature of the occasion to mirror the consecration ceremonies of priests. The coronation was commemorated in verse in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, while another chronicler, John of Worcester, described it as a service of “great pomp and ceremony”.

E is for… Edward VIII

In January 1936, Edward, Prince of Wales, succeeded his father, George V, as king of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, as well as emperor of India. He would never be crowned, though. In December that year, with his coronation still five months away, he abdicated the throne following disquiet about his relationship with the divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson. Edward didn’t attend the subsequent coronation of his brother, George VI, nor that of his niece, Elizabeth II, in 1953. He and Simpson watched Elizabeth’s coronation on television at their home in Paris.

F is for… fiasco

High-profile and complex occasions that they are, coronations have the potential to go wrong – and in full public view. In 1902, the coronation of Queen Victoria’s successor Edward VII (rescheduled after the king suffered a near-fatal bout of peritonitis) didn’t go particularly smoothly. Officiating the ceremony was the octogenarian archbishop of Canterbury, Frederick Temple, who by then was almost blind. Despite having the service’s prayers reproduced on large cue cards, he still stumbled over his words. When it eventually came to crowning Edward, not only did the archbishop nearly drop the crown, but he also managed to place it on the monarch’s head back to front.

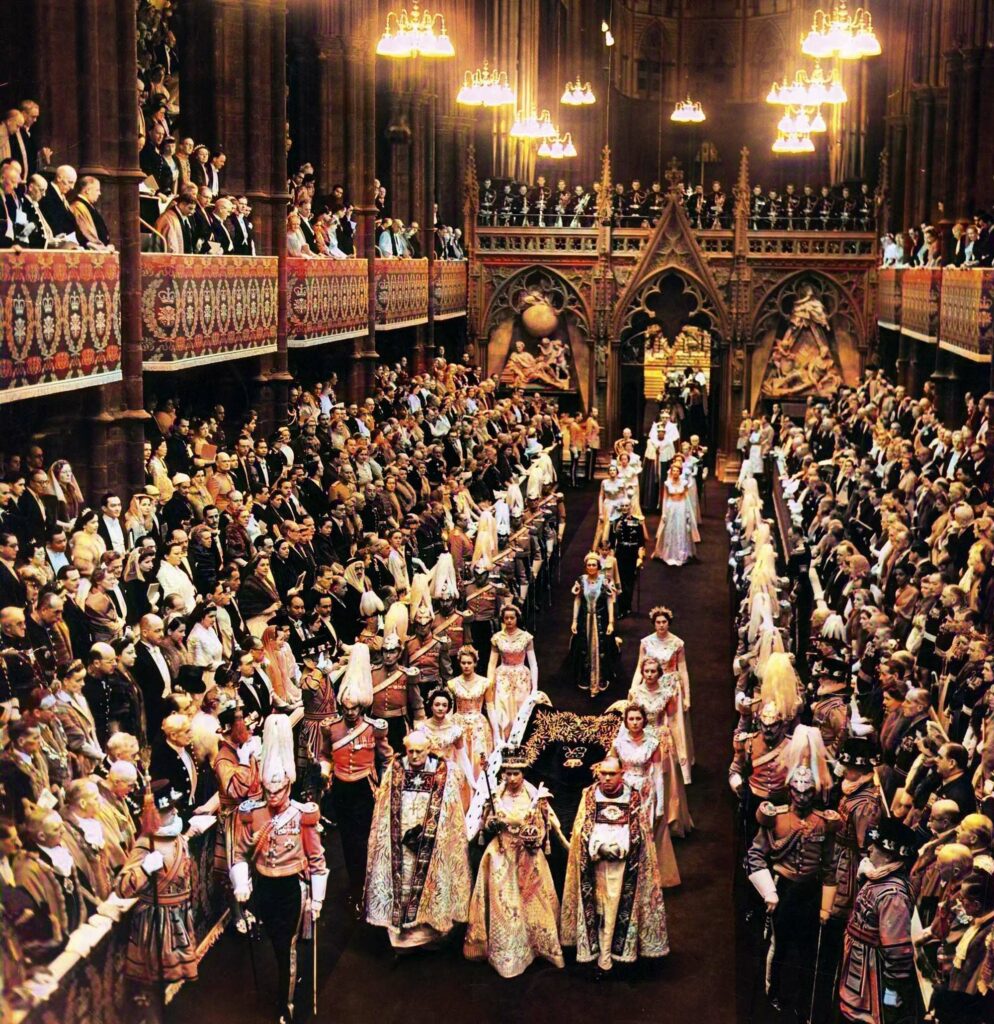

G is for… guests

The coronation of a British monarch with the longest guest-list was that of Elizabeth II in 1953. A total of 8,251 dignitaries crammed into Westminster Abbey to observe the ceremony, representing 129 countries and territories from across the globe. One of the most conspicuous royal guests was Sālote Tupou III, the long-serving queen of Tonga who stood at nearly two metres tall and was described by Princess Astrid of Sweden as “everyone’s darling”. The forthcoming coronation of Charles III will be notably less well-attended, with only a quarter the number of guests who attended his mother’s service taking their seats inside the abbey.

H is for… honours list

An impending British coronation is preceded by the issuing of a coronation honours list that confers orders and honours on notable members of society. It’s a tradition that’s been in place for 200 years, since George IV further endowed his already lavish coronation in 1821 with bestowing the titles. As with royal birthday honours, the list is drawn up by the prime minister of the day – and not always to the monarch’s complete satisfaction. Indeed, George IV blocked some of the recommendations of the Earl of Liverpool after growing disgruntled at the prime minister’s assumption that the king would merely rubberstamp the nominations without scrutiny.

I is for… infant

At the age of 74, Charles III will be the oldest British monarch to be the subject of a coronation, a scenario that’s in marked contrast to the experience of Henry VI. Henry had yet to reach his first birthday when he succeeded both his father, Henry V, as English king and his maternal grandfather, Charles VI, as French monarch. It wasn’t until he was seven years old that he had a coronation at Westminster Abbey, and two years later, just after turning 10, he was crowned in Paris in an attempt to delegitimise the claim to the French throne of Charles VII.

“Henry VI had yet to reach his first birthday when he became king”

J is for… jewels

The coronation of the monarch is, of course, further illuminated by the Crown Jewels worn and held by the new king or queen. Aside from the Sovereign’s Orb, which is placed in the monarch’s right hand during the service, and the Sovereign’s Sceptre, the – erm – crowning glory is the headwear. St Edward’s Crown was made in 1661 for the coronation of Charles II after the original crown was melted down after the abolition of the monarchy 12 years earlier. But it’s not the only crown worn on the day. The monarch leaves Westminster Abbey with the Imperial State Crown on their head instead. Lighter than St Edward’s Crown, it is still encrusted with 2,901 precious stones.

K is for… King Misuzulu

When he was crowned Zulu king in 2022, Misuzulu ka Zwelithini was the first to enjoy a coronation in South Africa’s post-apartheid era. He succeeded his father, King Goodwill Zwelithini, who had been the longest-serving Zulu king in history, having taken to the throne back in 1971. The then white-minority government had expected Goodwill to wear western clothing at his coronation, to which he complied, albeit with the inclusion of a leopardskin sash. By contrast, in the age of the republic, King Misuzulu attended his own coronation in exclusively traditional Zulu clothing.

L is for… locked out

When a married British king is crowned, he is always accompanied by his queen consort. Well, almost always. In 1821, George IV didn’t just choose to go solo at his coronation, but he actively barred his queen consort, Caroline of Brunswick, from the ceremony, having her locked out of Westminster Abbey. The couple had formally separated a year after their wedding in 1795 and relations between them were so acrimonious that George didn’t even inform Caroline of the death of their only daughter, Princess Charlotte, in childbirth. On the day of the coronation three and a half years later, Caroline attempted to enter the abbey via various entrances, but was rebuffed each time. She died less than three weeks later.

M is for… meals

Between 1189 and 1821, it was customary for a coronation banquet to be held after the ceremony, usually in nearby Westminster Hall. The newly crowned monarch would, of course, be the guest of honour, with large numbers of dignitaries also attending the feast, but William IV abandoned the tradition in 1830, believing it to be an unjustified expenditure, and it has never been held since. However, food would enjoy a connection with a coronation when, in 1953, coronation chicken – a dish of chicken in a creamy, curry flavoured sauce – was created by two London chefs in honour of Elizabeth II’s crowning.

N is for… new era

The crowning of Mary I in 1553 was the last English coronation to be held as an exclusively Catholic service. When her half-sister Elizabeth succeeded her five years later, the younger sibling’s coronation signalled her intent to forge ahead with the Protestant Reformation that Mary’s reign had attempted to reverse. Elizabeth not only insisted that the service be conducted in English as well as Latin, but she also sidestepped her participation in the Mass, with one eyewitness account reporting that she instead retired to an adjacent curtained-off area.

O is for… oil

The holy oil used to anoint a new British monarch (see ‘U’ below) is delivered by way of the 12th-century Coronation Spoon, the oldest item in the Coronation Regalia. The new king or queen is anointed on three different parts of the body: the hands, the breast and the head. The oil that is scheduled to be used at Charles III’s coronation has been both prepared and blessed in Jerusalem. Made from pressed olives, it has been infused with rose, jasmine, amber, sesame and cinnamon among other ingredients.

P is for… Penny Coronation

William IV was a very different monarch to his predecessor, his brother George IV. When the latter enjoyed the extravagance that came with his role, while also largely confining himself to Windsor Castle, William was more a man of the people. George’s coronation in 1821 had cost the tidy sum of £240,000. When his younger sibling inherited the throne nine years later, he saw no need for a coronation, let alone an expensive affair. William was ultimately persuaded to go ahead with the ceremony, although he ensured that it cost only an eighth of that of George’s. Traditionalists threatened to boycott the day, mocking the king’s frugal ways, referring to it with a scoff as ‘the Half Crown-nation’ – or the Penny Coronation.

Q is for… queen consorts

While the husbands of new queens aren’t crowned (and, indeed, usually have to make do with un-kingly titles like prince consort), wives of new kings are bestowed with the suitable headwear – as well as being given the official title of queen consort while being styled as queen. Queen Camilla will be the eighth female consort since the formation of the United Kingdom in 1707. For the coronation, she has opted to wear a modified version of the crown worn by Queen Mary in 1911, rather than that of the last queen consort, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, which contains the controversial Koh-i-Noor diamond, of which India continues to claim ownership.

R is for… robes

Several robes are worn by a British monarch at their coronation. First there’s the colobium sindonis, a plain, sleeveless tunic that represents the humility of its wearer before God. After the monarch is anointed, the tunic is placed over their existing clothing. Then, over the tunic, the distinctly more showy supertunica is worn, a full-length golden robe made of silk and believed to be influenced by Byzantine clothing. A robe of purple velvet is then worn after the investiture and crowning.

“The tunic represents its wearer’s humility before God”

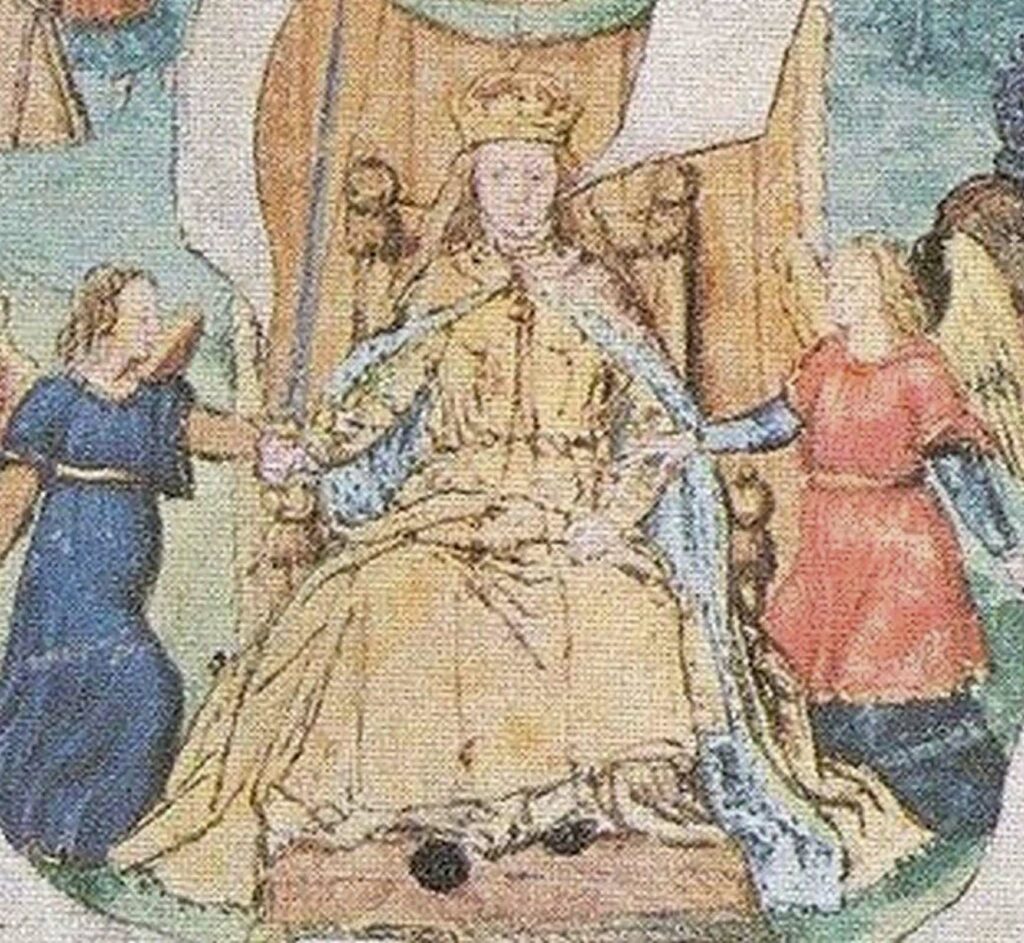

S is for… stone

Just as symbolic an element of a British coronation as the jewellery and regalia is something less glamorous: a block of sandstone known as the Coronation Stone. Its place in Scottish history is sacred, with its use in the coronation of monarchs north of the border dating back many centuries. For King Charles III’s coronation, it will be placed underneath King Edward’s Chair, as per tradition (as seen here).

T is for… television

The BBC Television Service was only six months old when it made its first outside broadcast beyond the environs of its Alexandra Palace headquarters – at the 1937 coronation of George VI, where it deployed just three cameras to record the royal procession. Sixteen years later, the corporation used 21 cameras at the coronation of Elizabeth II. It was the new queen who, against the counsel of many of those around her, permitted the live broadcast. As a result, more than 20 million Britons gathered around television screens to watch the event from close quarters.

U is for… unction

Unction is the process by which a new monarch is anointed using holy oil (see ‘O’ above). In the case of a British monarch, it occurs prior to both the investiture and the crowning, and emphasises their spiritual status in the eyes of God. Although television cameras were present inside Westminster Abbey for Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953, her anointment was concealed from public view beneath a gold cloth canopy. It has been reported that, for Charles III’s anointment, the canopy will have a transparent roof, thus the unction will be witnessed for the first time by guests and the huge television audience alike.

V is for… Victoria

To say that the coronation of Queen Victoria in 1838 was lacking in both preparation and rehearsal is something of an understatement. The ceremony was littered with problems and mistakes, including the coronation ring being placed on the wrong finger of the queen, causing her plenty of pain, and one of the more senior attendees, Lord Rolle, falling down some steps. The most embarrassing moment of all was when Victoria, having been informed by one of the bishops that the ceremony had finished, left to get changed out of her coronation attire, only to be retrieved for the remainder of the service. Her future prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, noted that the participants “were always in doubt as to what came next”.

X is for… Xmas Day

One of the more notable coronations of an English monarch took place on Christmas Day in 1066. Held fewer than three months after William the Conqueror’s victory at Hastings, it wasn’t the usual, joy-filled occasion that subsequent coronations would be. A nervous atmosphere fell on Westminster Abbey, with English soldiers attending alongside their Norman counterparts so soon after hostilities had ended. The atmosphere was the least of it. When the crowd cheered their approval of the new king, the noise was misinterpreted by William’s men outside as an attempt on his life. They set surrounding buildings on fire and a riot broke out, which forced the congregation to flee. The clergy and the new king completed the service in an otherwise empty abbey.

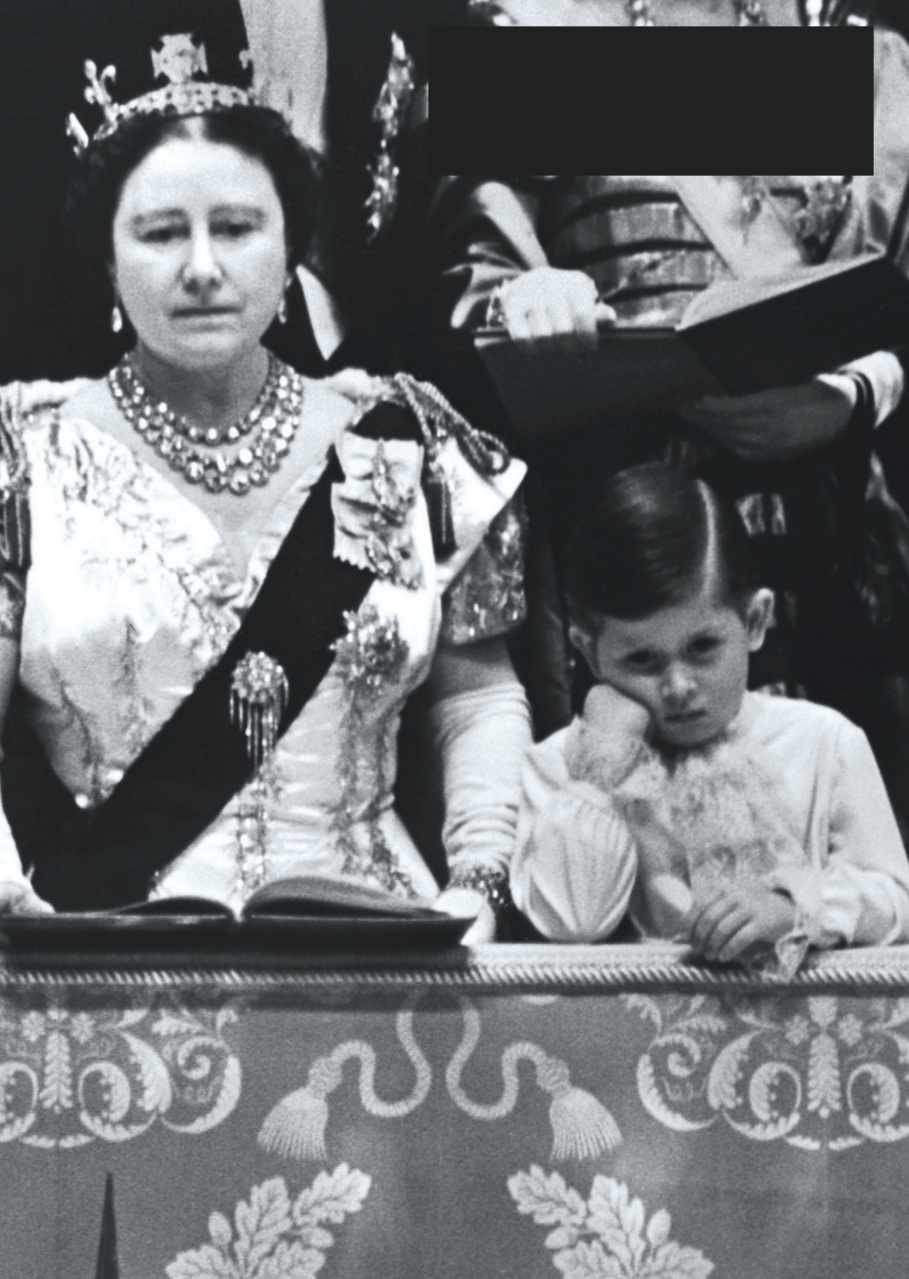

Y is for… young attendees

When the four-year-old Prince Charles attended his mother’s coronation in 1953, he was the first-ever heir to the throne to be present at the crowning of their mother. The young prince had received a special hand-painted invitation to the event, but that was arguably as exciting as it got for him. Photographs captured on the day show a very visibly bored boy enduring, not enjoying, the three-hour-long ceremony.

W is for… Westminster Abbey

Coronations of almost all English monarchs have been held at Westminster Abbey, with Harold II probably the first king to be crowned there, in 1066. Built by Edward the Confessor on the site of a Benedictine monastery, the original abbey was in use until the 13th century when Henry III had it rebuilt in a Gothic style. Henry’s ambitions for the abbey were that it would be the permanent location of all future coronations. More than 700 years later, it still is.

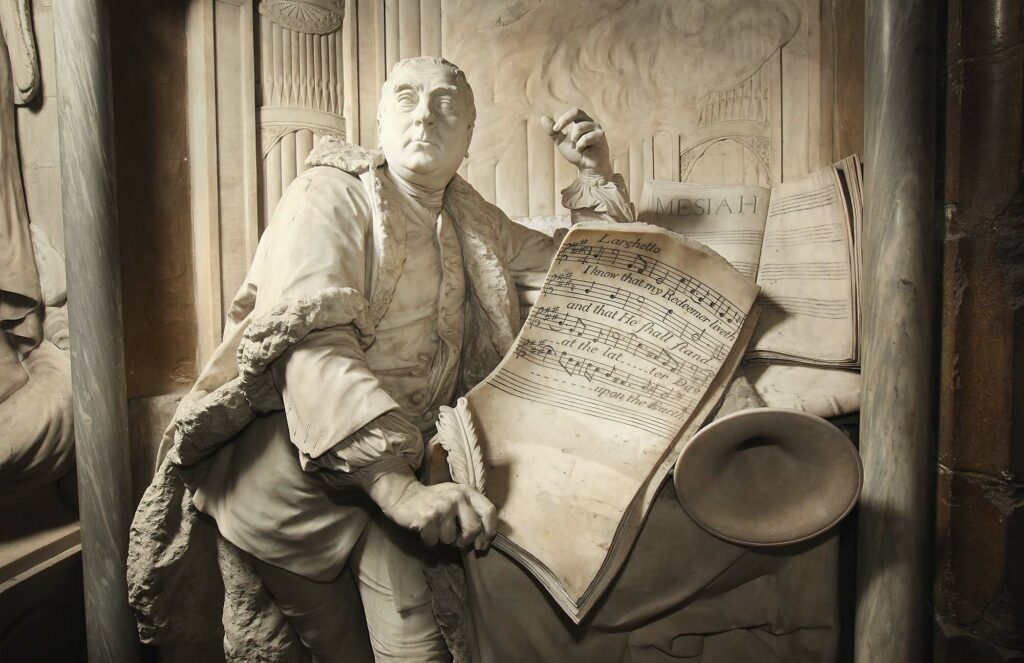

Z is for… Zadok the Priest

In 1727, the year he became a naturalised British subject, Germanborn composer George Frideric Handel was commissioned to write an anthem for the coronation of George II. The result was Zadok the Priest, a work that has been sung at every British coronation since. Its lyrics derive from the Book of Kings in the Bible and are an account of King Solomon being anointed by the titular priest. Accordingly, the line “God save the King! Long live the King! God save the King!” pertains to Solomon and not to the monarch actually being crowned on that day. Accordingly, the words are not changed when the ceremony is for a new female monarch.

READ AND LISTEN

For more on the upcoming coronation of King Charles III, visit historyextra.com. TAP HERE for our guide to the best TV and radio coverage.