OLDEST HUMAN DNA EVER FOUND IN THE UK REVEALS TWO DISTINCT POPULATIONS MIGRATED HERE FROM EUROPE

The remains of the ancient Britons were discovered in caves in Somerset and North Wales and date back more than 13,500 years

At least two genetically distinct groups of people made their way to Britain at the end of the last ice age, an analysis of the oldest human DNA discovered in the country has found.

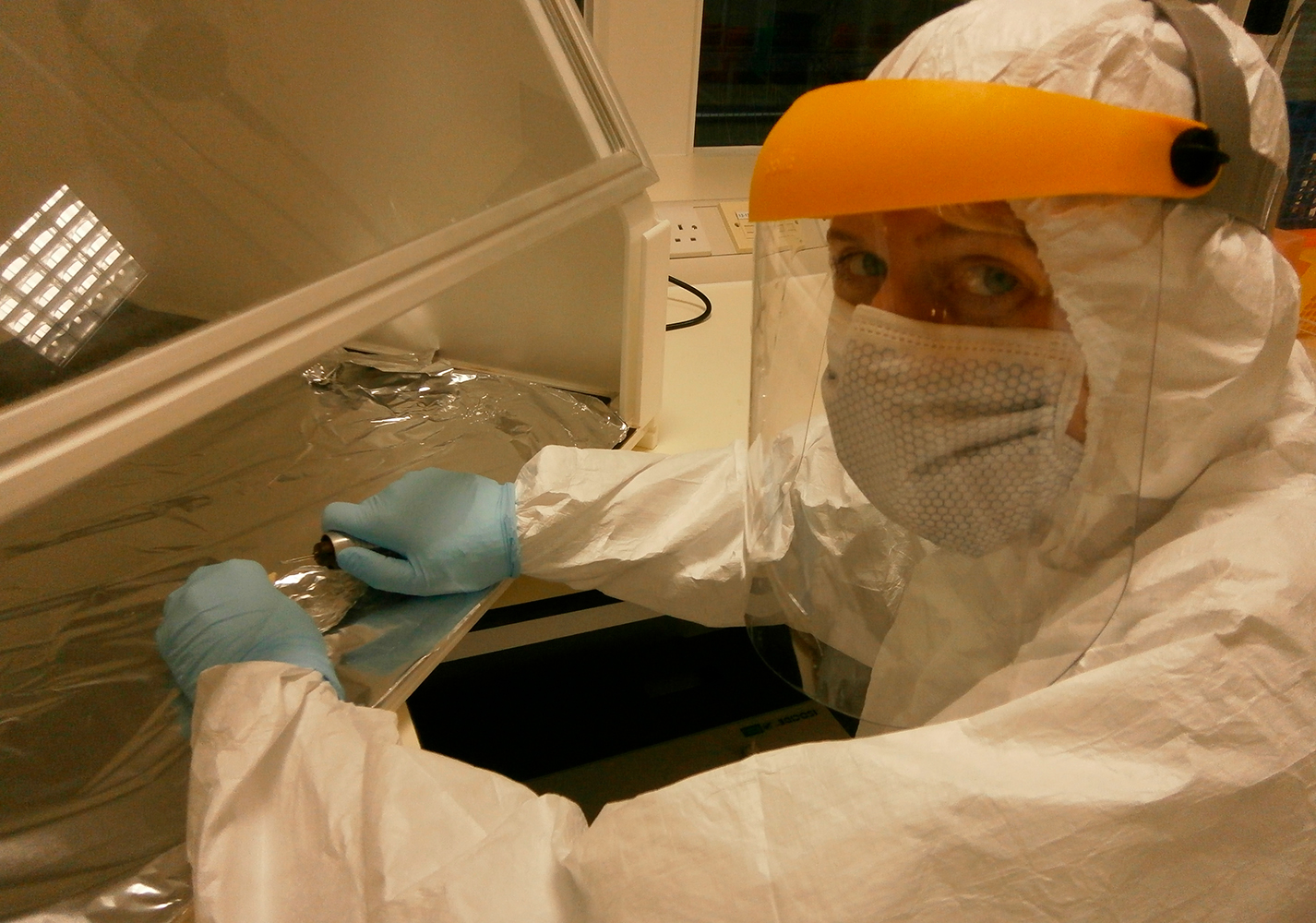

To make the discovery, researchers from University College London, the Natural History Museum and the Francis Crick Institute analysed the remains of two ancient humans using radiocarbon dating and genome sequencing techniques.

One, a female unearthed from Gough’s Cave in Somerset, was found to have lived around 15,000 years ago. She belonged to a group known for their use of stone tools and production of cave art, that moved through northern Europe around 16,000 years ago.

The other, a male found in Kendrick’s Cave, North Wales, lived around 13,500 years ago and belonged to a group known as western hunter-gatherers, who migrated to Britain around 14,000 years ago from the Near East.

Around 17,000 years ago, as the last ice age was coming to an end, the climate in the UK began to warm. As temperatures increased, the glaciers that covered much of the country began to melt. The increasingly favourable conditions led to groups of Palaeolithic humans making their way to the UK from the continent.

“The Old Stone Age is an important time period for the environment in Britain”

“The period we were interested in, from 20,000 to 10,000 years ago, is part of the Palaeolithic – the Old Stone Age. This is an important time period for the environment in Britain, as there would have been significant climate warming, increases in the amount of forest, and changes in the type of animals available to hunt,” said Dr Sophy Charlton, formerly of the Natural History Museum but now a lecturer in bioarchaeology at the University of York. “There are very few human remains of this age in Britain; perhaps around a dozen individuals from six sites.”

As well as differing genetically, the two groups also differed culturally, having different diets and ritualistic practices.

“Chemical analyses of the bones showed that the individuals from Kendrick’s Cave ate a lot of marine and freshwater foods, including large marine mammals,” said study co-author Dr Rhiannon Stevens, from University College London.

“Humans at Gough’s Cave, however, showed no evidence of eating marine and freshwater foods, and primarily ate terrestrial herbivores such as red deer, bovids – such as wild cattle called aurochs – and horses.”

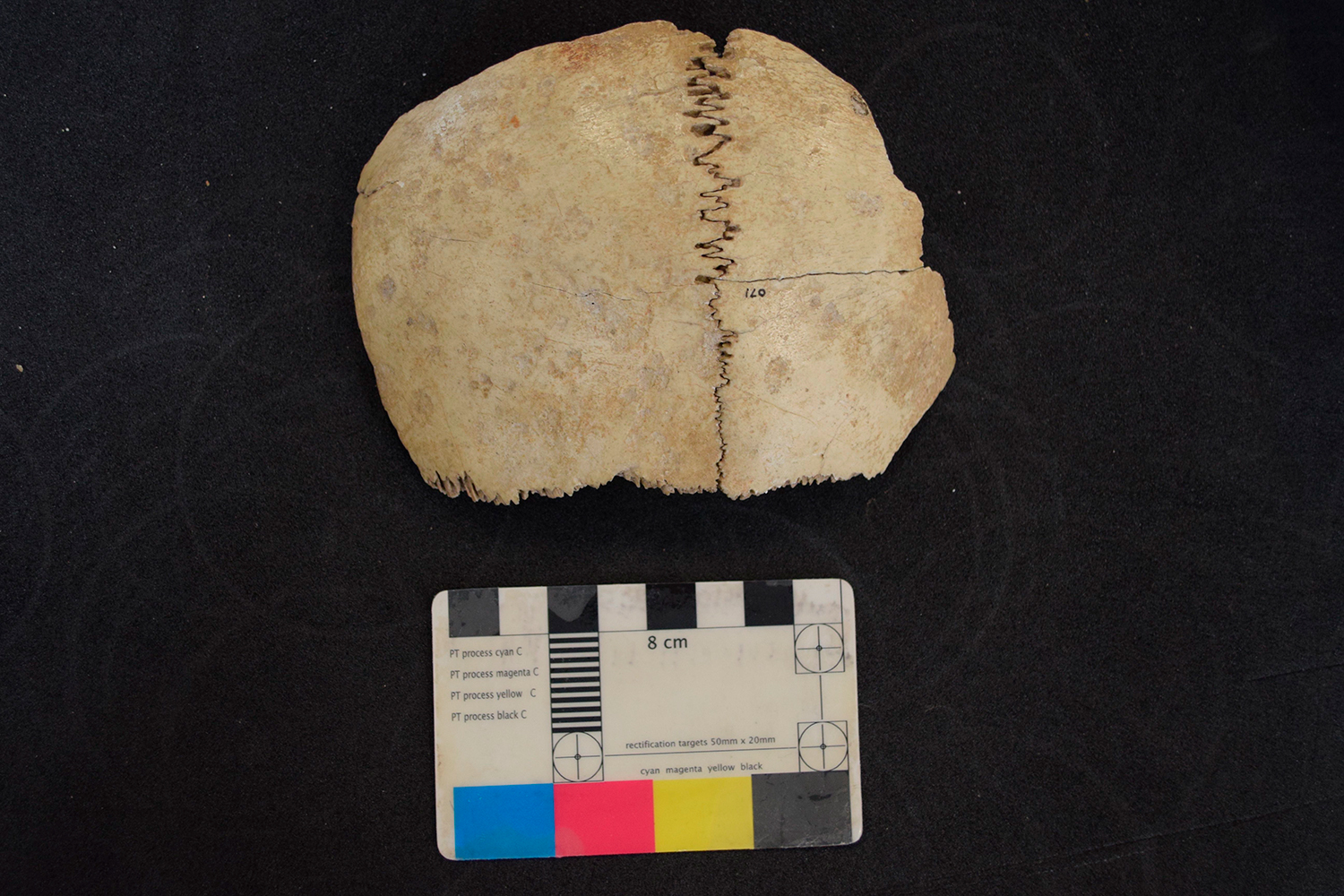

In Kendrick’s Cave, decorated animal bones were found alongside the human remains, while Gough’s Cave contained cups made from modified human skulls – an indication of ritualistic cannibalism.

Studies of remains from other areas in the UK and across Europe are now needed in order to help fill out the picture further, the researchers say.

“Finding the two ancestries so close in time in Britain, only a millennium or so apart, is adding to the emerging picture of Palaeolithic Europe, which is one of a changing and dynamic population,” said Mateja Hajdinjak, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Francis Crick Institute.