LIKE MODERN HUMANS, HOMO NALEDI HARNESSED FIRE FOR LIGHT, WARMTH AND COOKING

Researchers excavating South Africa’s Rising Star cave system have unearthed evidence that Homo naledi, an extinct species of hominid discovered in 2013, built fires in underground chambers

I t’s often said the ability to make fire is one of the key skills that defines Homo sapiens – it allowed our ancestors to cook food, keep warm and eventually become the most dominant species on the planet.

Recently, evidence has been found across Europe to suggest that Neanderthals were also skilled fire users, but now we may have to add another species to the list. Researchers excavating a complex network of caves in South Africa say they have unearthed evidence that Homo naledi, an extinct species of hominid that lived 200,000 to 300,000 years ago, also used fire.

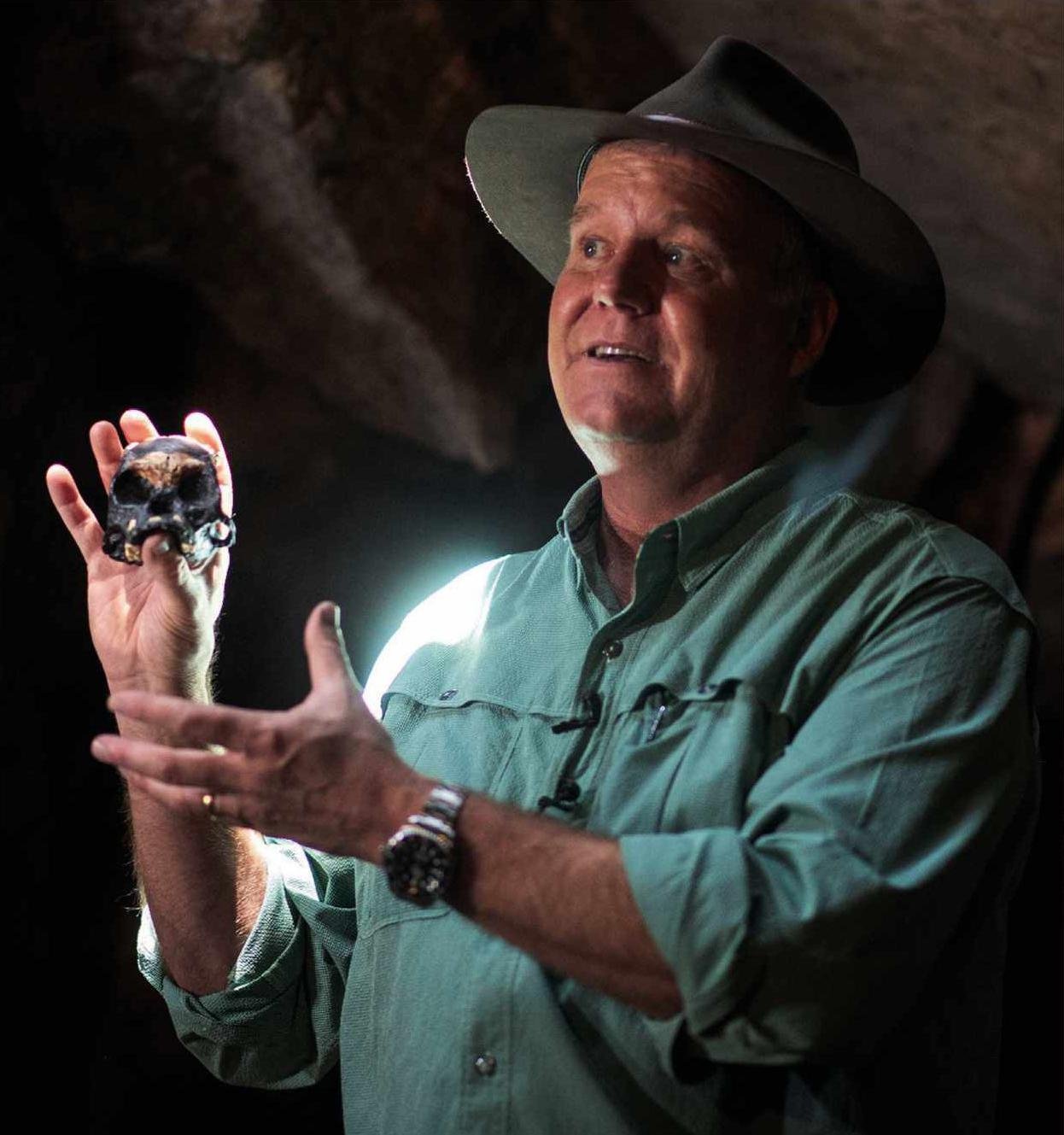

The finding was announced at a lecture given at the Carnegie Institution of Science in Washington, DC, on 1 December by Prof Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

“We’re fairly confident to formulate the hypothesis that this small-brained hominid, Homo naledi, [which] existed at the same time we believe Homo sapiens were sharing parts of Africa, was using fire for a variety of purposes,” he said.

H. naledi was discovered in 2013 by a team of excavators, led by Berger. The remains were found hundreds of metres into a claustrophobically tight network of passages known as the Rising Star cave system near Johannesburg.

“There were blackened areas across the wall. There were soot particles across the whole of the surface”

Subsequent excavations have since unearthed fossils from more than a dozen individuals (male and female, juvenile and adult) as well as evidence of ritualistic burial practices in which the remains of certain individuals appear to have been washed and deliberately placed in position.

Then, earlier this year, Berger finally entered the difficult-to-reach network of caves for the first time himself. And once he was inside the chamber where his team found the H. naledi remains, he noticed evidence of soot on the cave’s surfaces.

“As I looked up and stared at the roof, I began to realise that the roof was not a pure calcium carbonate. The roof above my head was grey above fresh flowstone. There were blackened areas across the wall. There were soot particles across the whole of the surface. The entire roof of the chamber where we have spent the last seven years working is burnt and blackened,” he said.

At the same time, the expedition’s co-director, Dr Keneiloe Molopyane, uncovered the remains of a small hearth containing burnt antelope bones, as well as the remains of a much larger hearth in a nearby cave.

Further investigation of the cave system led to the team finding several other caves and passages containing chunks of burnt wood and charred animal bones.

“Fire is not hard to find. It’s everywhere within this system,” said Berger. “Everywhere there’s a complex juncture, they built fire. Every adjacent cave system to the chambers where we believe they were disposing of the dead, they built fires and cooked animals. And in the chamber where we believe they were disposing of the dead, they built fire but didn’t cook animals. That’s extraordinary.”

The team now plans to work on radiocarbon dating their finds in an attempt to confirm the link between the hearths and the H. naledi fossils.

“This is the most extraordinary period of exploration and discovery. And it’s going to continue,” said Berger.