WORLD’S OLDEST MEAL FOUND IN 550-MILLION-YEAR-OLD FOSSILS

The bizarre ocean-dwelling creatures are relatives of all living animals

T he contents of the last meal eaten by one of the world’s first large animals has been discovered by researchers from the Australian National University (ANU). It is the earliest evidence of food eaten by an animal, they say. The team analysed a pair of Ediacara biota fossils, which are ancient forms of life that are the ancestors of all living animals and were the first creatures to develop bodies with features such as heads, tails and guts more than 550 million years ago.

To determine what the animals had been eating, they analysed the fossils in search of preserved phytosterol molecules, which are natural compounds found in plants. It turns out they ate green algae and bacteria.

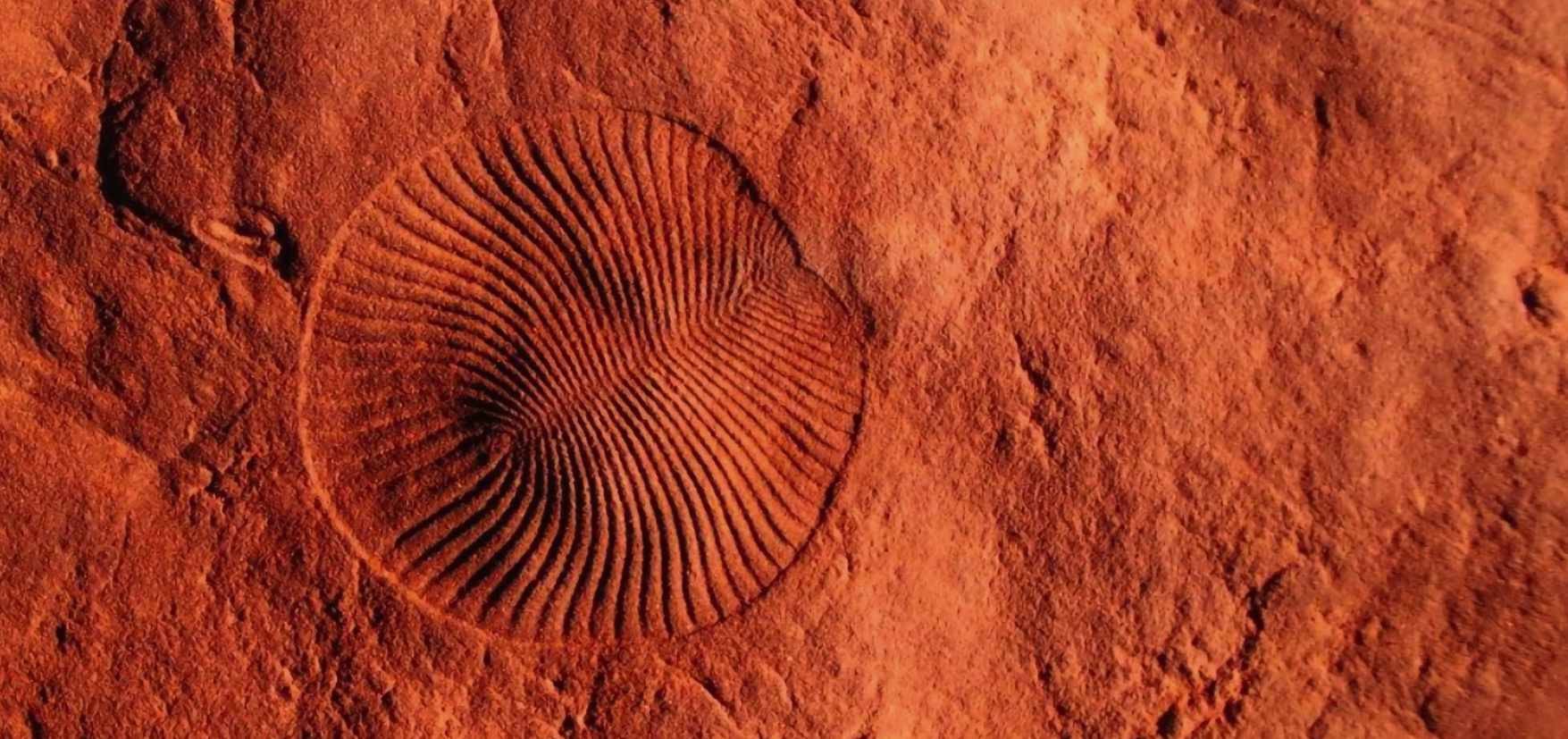

One of them, a slug-like creature called Kimberella, ate via a mouth and digested the food in a gut much in the same way that modern animals do. The other – Dickinsonia, which looked a bit like a ribbed flatfish and measured 1.4m long – was a more basic beast with no eyes, mouth or gut, and likely absorbed food through its body as it moved along the ocean floor.

“Animals of the Ediacara biota were a mixed bag of downright weirdoes such as Dickinsonia, and more advanced animals like Kimberella”

“Ediacara biota really are the oldest fossils large enough to be visible with your naked eyes, and they are the origin of us and all animals that exist today. These creatures are our deepest visible roots,” said Dr Ilya Bobrovskiy from the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, who collaborated on the research.

“Our findings suggest that the animals of the Ediacara biota were a mixed bag of downright weirdoes such as Dickinsonia, and more advanced animals like Kimberella that already had some physiological properties similar to humans and other present-day animals.”

The researchers speculate that the energy-rich diet of Edicara biota may be one of the reasons they were able to grow so much larger than the microorganisms that came before them.

“Scientists already knew Kimberella left feeding marks by scraping off algae covering the sea floor, which suggested the animal had a gut,” said the study’s co-author Prof Jochen Brocks of ANU.

“But it was only after analysing the molecules of Kimberella’s gut that we were able to determine what exactly it was eating and how it digested food.”