THE LONELY HEARTS CLUB MAN

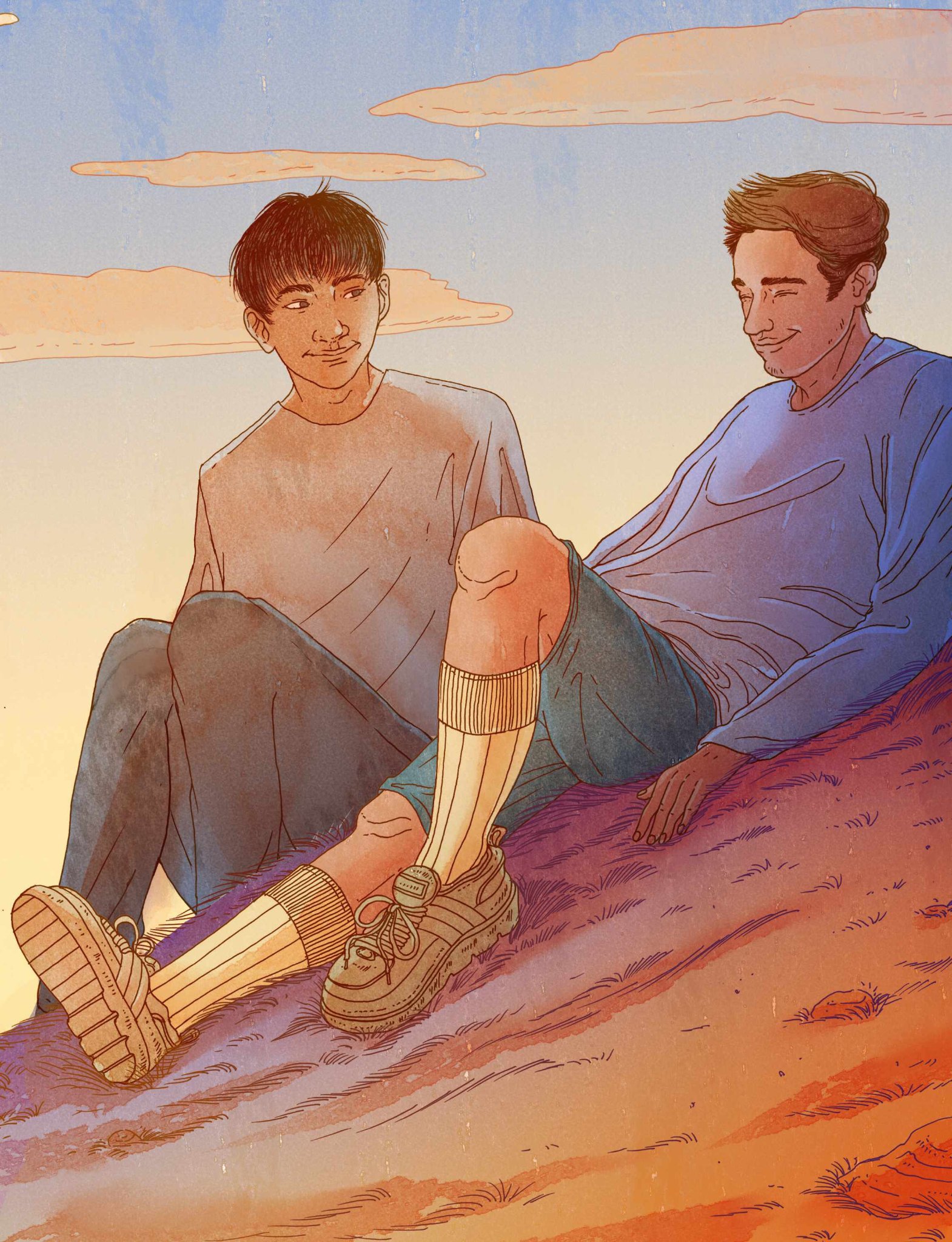

MEN ARE LOSING FRIENDS AND STRUGGLING TO MAKE NEW ONES – AND MISSING OUT ON POWERFUL HEALTH BENEFITS IN THE PROCESS. BUDDY, WHAT’S GOING ON?

Back in 2008, a small but very cute study asked people to stand at the bottom of a hill, look up and guess how steep it was. Some people were there alone, others accompanied by friends. The hill, on the campus of the University of Virginia, had an incline of 26°. But to the people who were there with friends, it looked a lot less. Compared with those who turned up on their own, they significantly underestimated the gradient. The feel-good lesson? Everything looks easier when there’s a friend by your side.

Yes, mate, the benefits of friendship are profound. Having a strong social circle is associated with a longer life and fewer illnesses. Your pals lower your blood pressure and trigger positive chemicals in your brain. People with a strong social network are less stressed, more resilient and more optimistic. They’re more likely to be a healthy weight and less likely to suffer cognitive decline. They also enjoy some protection from cancer, heart disease and depression.

But there’s one group – a big one – that is missing out on these benefits. Men are lonely. Growing numbers of men are standing at the bottom of that hill, alone and overwhelmed, as surveys point to a recession of social connection among those of us with a Y chromosome.

A YouGov poll in 2019 concluded that one in five men have no close friends, twice as many as women. In 2021, the Survey Center on American Life found that since 1995, the number of American men reporting that they had no close friends jumped from 3 to 15 per cent. In the same research, the number of men saying they had at least six close friends halved from 55 per cent to 27 per cent.

Why do men struggle to make or maintain friendships? And what can we do about it, not just as individuals but on a societal level? Because the sad truth is, an empty social calendar is the least of Billy No-Mates’ problems. Loneliness is a health hazard, as dangerous as smoking or alcoholism, according to some research.

A major study by scientists at Brigham Young University in the US found that long-term social isolation can increase a person’s risk of premature death by as much as 32 per cent. For this reason, some have called it the ‘shadow pandemic’. It was brought into focus during the COVID-19 lockdowns, when all of us were isolated and friendship became a hot research topic again, but it had spread around the world long before the novel coronavirus had.

“It’s a story I’ve been telling for 30 years,” says Prof Niobe Way, of New York University. As a developmental psychologist, Way has spent much of her career interviewing boys and men about their relationships, and how they change over time (documented in her book, Deep Secrets). She believes that hyper-masculine ideals are stripping young men of close friendships and the intimacy that goes with them.

“When you speak to boys aged 11, 12 or 13, they have this natural capacity and desire for closeness. And it’s not a bromance thing, it’s not just wanting to have dudes to hang out with. It’s wanting someone they can share their secrets with,” she says. “Then you speak to them again around 15 or 16 and you get this stereotype creeping into the responses. They start saying things like, ‘Oh sure, I have friends, everyone’s my best friend, I don’t care, it doesn’t matter.’”

MACHO MAN?

Way admits that young men being macho about their friendships is nothing new, but she thinks it’s telling that a change occurs in adolescence that – seemingly – frames the way a lot of men form and maintain their relationships all the way through adulthood.

If you’ve ever watched a sitcom, you know how it goes: men have superficial or transactional relationships with each other and bond by banter as they watch sport or drink beer. Women, in contrast, have deep and emotionally vulnerable conversations marked by shared secrets and interpersonal closeness. The funny thing is, these sitcom stereotypes are borne out by research.

“FOR MEN, WHAT MAKES THE DIFFERENCE IS INVESTING TIME IN DOING SOMETHING TOGETHER. IT MIGHT BE MEETING UP FOR A PINT OR ARRANGING TO CLIMB BEN NEVIS”

“One of the main things we’ve shown is that the two sexes are very different in their social style,” says Prof Robin Dunbar, an anthropologist at the University of Oxford whose work centres on social bonding. “The girls’ social world has been built around personalised relationships. It matters who you are, not what you are.

“For men, what makes the difference is investing time in doing something together. It might be meeting up for a pint or arranging to climb Ben Nevis. The activity is irrelevant as long as it’s a group activity – and that often doesn’t involve a lot of conversation. There’s a bit of banter but really, the content is close to zero.”

The difference between male and female friendship is often characterised as side-by-side versus face-to-face relationships. When men meet their friends, they stand shoulder-to-shoulder: at the bar, at the football ground, fishing at a river. When women meet up, they often sit across a table from each other and talk.

The emotional investment and frequent contact that women prize is not as important for men, Dunbar says. Men can go months without seeing a mate but still consider that person a close friend. Could this superficial approach to friendship explain why men are losing friends and more likely to feel lonely?

It’s almost certainly a factor, but it’s not the only one. Sociological and generational changes also play a part. It was only a few generations ago that, for the majority of people, friends were constants in our lives, like family. People moved less, travelled less, changed jobs less. Today, our mobility – literal and figurative – means that friendships can more easily come and go.

Loneliness and isolation can also happen as a consequence of other things, says Dr Mike Jestico, a psychologist at the University of Leeds who also works with local men’s groups in the city. “Homelessness, addiction, breakdown of family home… Men are more likely to experience these than women, leading to isolation,” he says.

“Isolation is more likely to happen to men with lower incomes, as social experiences tend to cost money. One of the men in my research sang in a social singing group. But when the group moved venues, he couldn’t afford the bus fare to travel, thus increasing his isolation.”

Jestico says that a kind of ‘structural’ isolation can also be a factor. Single men are more likely to live alone in high-rise tower blocks, for example, and are less likely to be the primary caregiver of children.

“The bedroom tax meant single men could not afford to live in accommodation with more than one bedroom and moved into smaller accommodation with some high-rise flats in Leeds having 75 to 80 per cent male residents in 2016. “One of my participants, who did not live with his children’s mother, was moved 15 miles from his two-bedroom flat to an affordable one-bedroom flat. This meant he lived further from his friends and children, who were much less likely to stay with him as he only had one bedroom.”

There’s more too. Throw in working from home, the closure of pubs, declining engagement in religious activities or social clubs, not to mention smartphone addiction and so-called social media, and perhaps the statistics on men’s shrinking friendship circles aren’t that surprising after all.

PLANS MAKE THE MAN

Another important factor is, of course, that men are a bit useless. When it comes to making plans or staying in contact with friends, men are socially lazy. This appears to be especially true in middle age when something strange happens with men’s friendships. At this age, men don’t appear to be lonely, on the surface.

“Data including men and women has often found a U-shaped relationship, where teenagers and the oldest people in society are the loneliest,” says John Ratcliffe, a researcher at the Centre of Loneliness Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. “That said, the highest suicide rates are in single men in their 40s and 50s.”

Men show a stronger link between marital status and loneliness than women, Ratcliffe says. Which is to say, unmarried women are less lonely than unmarried men. “I would link this statistical trend to a greater ‘reliance’ on partners for intimacy in men, and a greater ideation of the family role. For men who don’t have a partner, loneliness can be particularly severe.”

“BECAUSE MALES ARE SOCIALLY LAZY, WHAT TENDS TO HAPPEN IS THE WIFE ENDS UP DRIVING THE SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT FOR THE HOUSEHOLD”

But even for men who are coupled up, middle age is tricky territory. At this stage of life, guys might drop out of the five-aside team, or family commitments keep them from the after-work drinks or the hobbies they once had more time for. They may have fewer peers in the workplace, and the friends they see on a regular basis may not be particularly close ones.

“Because males are socially lazy, what tends to happen is the wife ends up driving the social environment for the household,” says Dunbar. “The guys end up becoming friends with the partners of their wives’ friends – because they’re there.”

Men’s reliance on their partners can also lead to further problems. For one, it places a lot of pressure on the women (in heterosexual relationships, at least), and if the relationship breaks down or the man is widowed, it can leave him abruptly isolated. “When you have a divorce or you’re widowed, suddenly half your social world vanishes overnight,” Dunbar says.

So what’s to be done? Way says that it has to start with boys, addressing the culture of masculinity that young men grow up in.

“The lack of friendships amongst men is just a symptom of the bigger problem. I feel like journalists – and social scientists – bring the microscope in too much. And so we only focus on this specific symptom,” she says. “If you bring up the microscope just a tiny bit, you begin to see this is just a symptom. Because boys do have and want close friendships.”

Way believes we should try to foster boys’ latent caring and emotional side. Being socially and emotionally intelligent is not a female trait, she says: it’s a human one. “We don’t have to teach it, we just have to nurture it.”

Dunbar is more cautious about dismantling the way boys and men socialise, arguing that you see the same behaviours in monkeys and apes that you see at nurseries, schools and workplaces. He pictures two Mediterranean men sitting outside a cafe in the sunshine. They smoke cigarettes, drink coffee and stay there for hours saying almost nothing to one another.

“Don’t knock it!” he says. “This is boys bonding. Girls would never do that because they would want to talk to each other, but for boys you can sit down in complete silence and still build a relationship, providing there’s an activity or some kind of focus.”

For Dunbar, finding a shared activity is key, and his advice to lonely men is to start there, by finding a club or something you’re interested in. “Dancing, singing, playing rugby or tennis, climbing hills – you name it. They all trigger endorphins. And when you do it with other people, you end up bonding. It’s a very powerful mechanism,” he says.

Volunteering has a similar effect, whether it’s something charitable, or getting involved in your children’s sports teams, or local political or environmental movements. In 2020, Dunbar and his colleagues published a pan-European study in which they found that your future risk of depression is lower if you take part in three voluntary activities.

This taps into another stereotype about men: as much as we want to be loved, we also want to be useful. “In my research, a sense of ‘worth’ is often central to non-loneliness in men,” says Ratcliffe. “That is, feeling accepted, respected, loved, and/or admired. It also appeared related to neurological stimulation – the idea of being positively occupied.”

Ratcliffe believes that building self-worth in young boys and lonely men alike is important to undo the pandemic of disconnection. At the same time, he wants to deconstruct masculine expectations that say you have to be invulnerable, that compel men to say they’re okay when they’re not, or that they’re not lonely when they are.

Part of this is realising that you’re not alone in feeling alone, adds Way. “We have to normalise it so that people don’t somehow think they’re weird, but that it’s actually that culture has made it very hard for you to find meaningful relationships.”

Want to make a start? Way suggests sending this article to men you know, whether or not you think they are lonely. “Lots of men need a jumping-off point to start having conversations with other men about this kind of stuff. Send them the article and just ask them: ‘What do you think?’” It could be the start of a beautiful friendship.

BUDDY SYSTEMS

SCIENTIFIC WAYS TO MAKE FRIENDS AND INFLUENCE YOUR LONG-TERM HEALTH

ASK QUESTIONS

Harvard neuroscientists found that talking about yourself triggers neural reward systems, just like food or sex do. So make your new acquaintance feel good by asking them about themselves and listening.

PUT THE TIME IN

According to a study at the University of Kansas, it takes 200 hours of socialising for somebody to become a close friend. That includes around 50 hours to upgrade from an acquaintance to a casual friend.

FIND COMMON GROUND

No surprise here: you need a few things in common. Anthropologist Prof Robin Dunbar’s seven pillars of friendship include things like world view (religion, morals or ethics), educational trajectories, as well as shared hobbies or tastes in music or humour.

GO TO THE SHED

Psychologist Dr Mike Jestico recommends seeking out local community groups, walking clubs or menssheds.org.uk. The latter is a network of community spaces where men are invited to connect and converse while doing things like crafts and DIY.

CHECK IN

Don’t underestimate the power of a quick call or message to a friend you haven’t seen or spoken to in a while. New research from the University of Pittsburgh found that check-ins like this are more deeply appreciated than most of us realise.

SING YOUR HEART OUT

Joining a club or group is one of the surefire ways to enhance your social circle, but if all else fails, join a choir. Dunbar says that singing has a seemingly unique ice-breaking effect, and people who sing together bond remarkably quickly.

(@IanStean) Ian is a freelance writer and editor.

Listen to The Anatomy Of Loneliness, available on BBC Sounds.