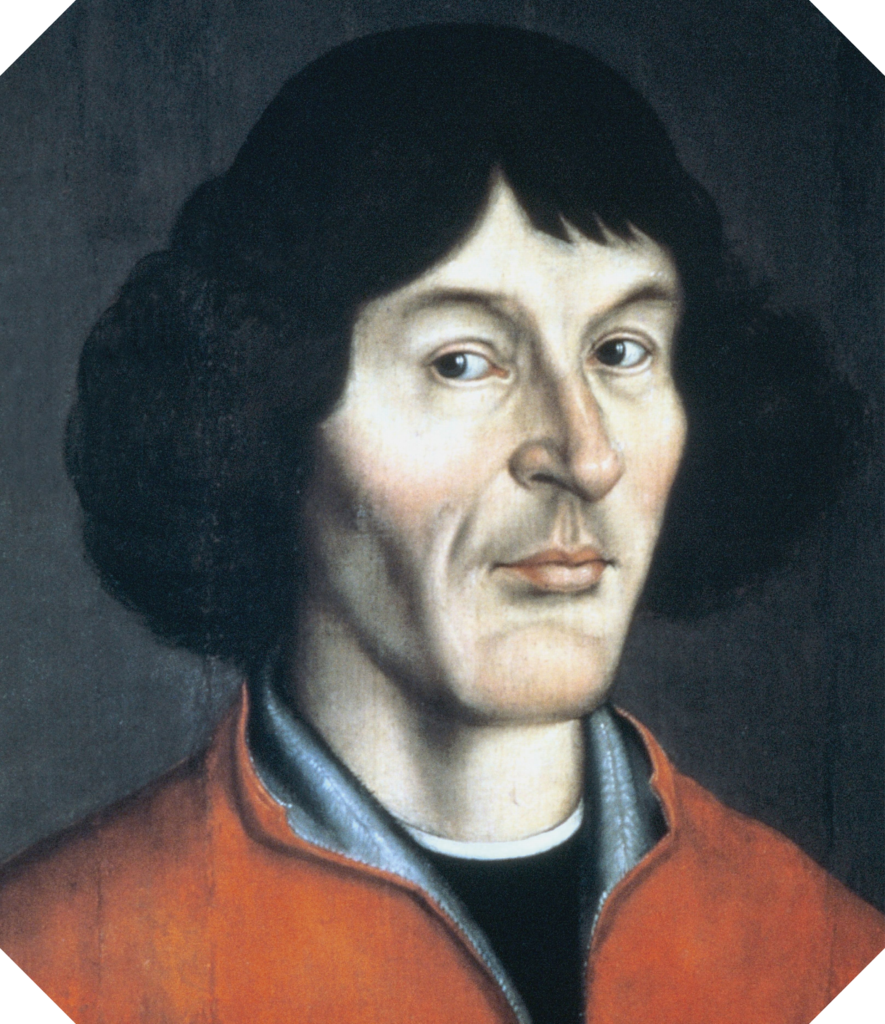

This month marks 550 years since the birth of Nicolaus Copernicus. Emily Winterburn explores his life and legacy

Today, Nicolaus Copernicus is a household name, well known as the astronomer who gave us the Suncentred model of the Universe. But what do we know about the man himself, and how did he go about revolutionisin our perception of the cosmos

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in Poland on 19 February 1473 and came from a wealthy, well-connected family. His father was a merchant, as was his maternal grandfather. The family had many connections to the Catholic Church which, at the time, put them in a powerful position in Poland. When Copernicus was 10, his father died and his uncle, Lucas Watzenrode – a high-ranking church official – took over control of his education. He was sent to a church school and then to the University of Kraków. European universities back then were places to train wealthy men to join the professions: law, church and medicine. Indeed, his studies at universities in Poland and Italy included these disciplines.

Old world order

The academic world of the 1400s and 1500s was very different to the world we know today. No one could study a degree in astronomy, and astrology was seen as a legitimate and important scientific subject. In Kraków, Copernicus began reading about astronomy and probably attended lectures by members of the Kraków School of Mathematics and Astrology. Even when he began studying medicine, he learned yet more astrology, as this was an integral part of medical knowledge at the time.

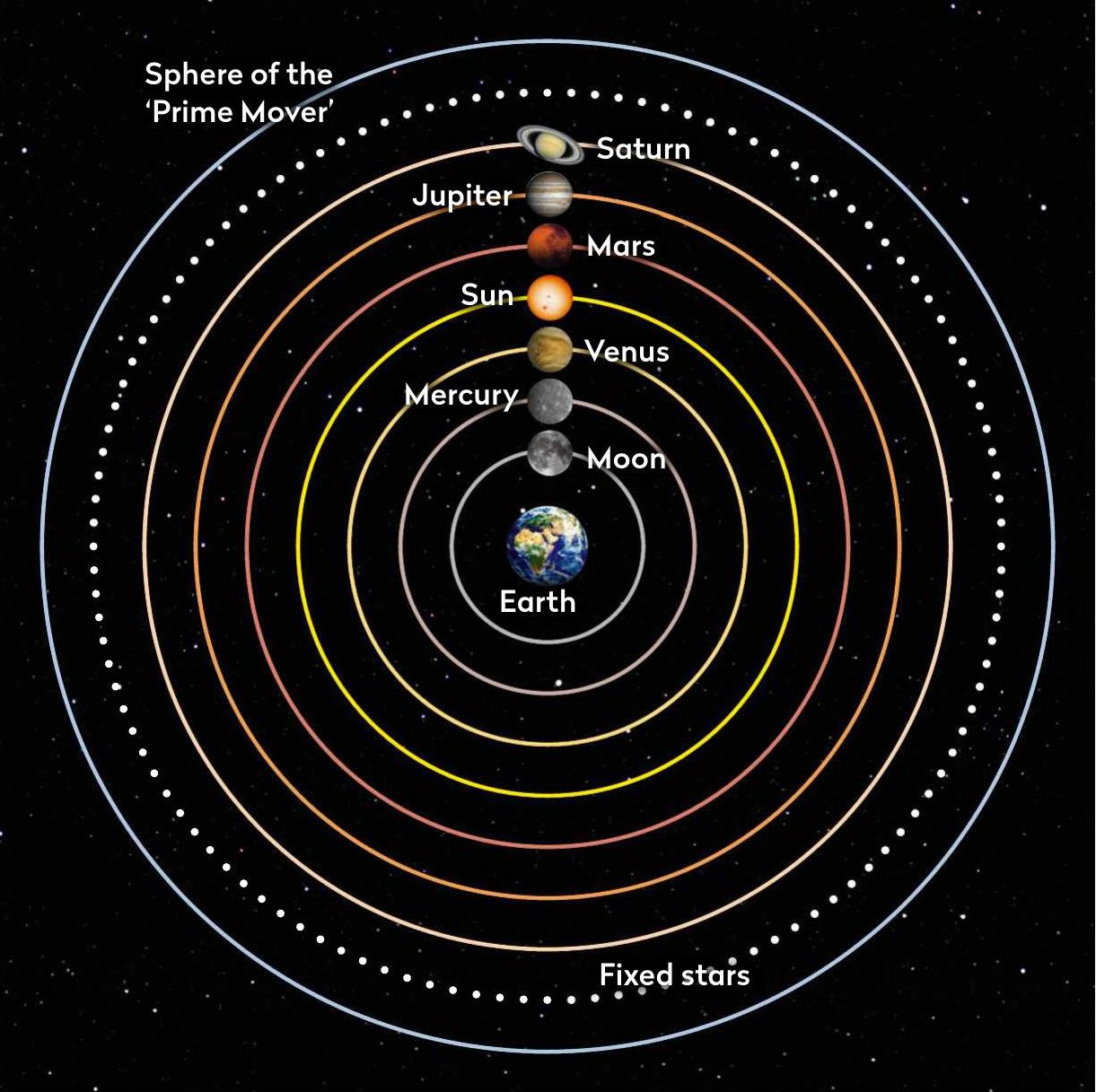

By the time he was 30, Copernicus had finished his studies and began working for his well-connected uncle as a secretary and physician. When his uncle, Watzenrode, died in 1512, Copernicus moved to Frombork on the Baltic Coast, which became his home for the rest of his life. At Frombork he continued reading about astronomy, which at the time still held to Aristotle’s model of the Universe, with the imperfect Earth at the centre surrounded by perfect, heavenly spheres.

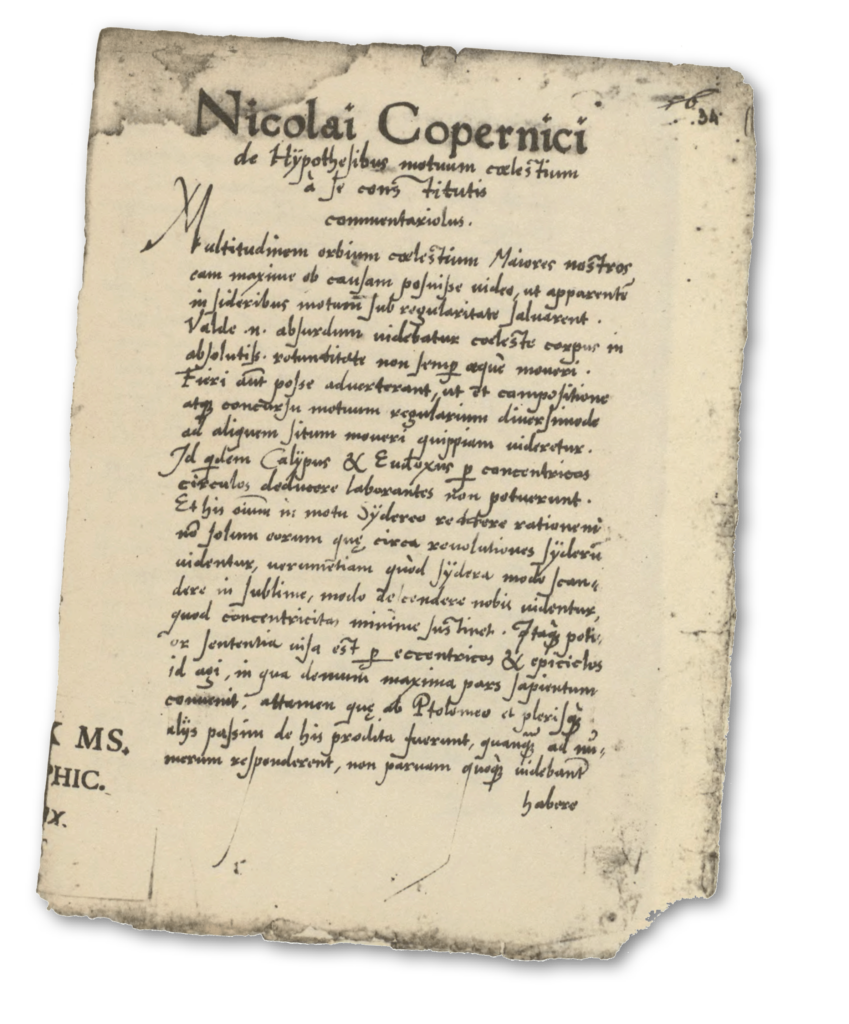

He observed the night sky, developing his ideas as he recorded his observations of planets and eclipses. He took up administrative and advisory roles within the church and state, and then in 1514 he wrote his first piece outlining his heliocentric model of the Solar System. This first draft, intended only for close friends and acquaintances, was called Commentariolus.

Changing views of the cosmos

Copernicus was very cautious about his theory and the potential upset it could cause, as Aristotle’s model was the one adopted by the church. This included Ptolemy’s addition of ‘epicycles’ (each planet moving in a small circle while on its larger orbital circle) to better account for the actual, observable movement of the planets, particularly retrograde motion. For a long time, Europeans stuck with this model. In the Islamic world, however, many mathematicians and astronomers were questioning and adjusting this model to make better sense of it. From the work cited in Copernicus’s texts we know that he was aware of at least some of these theories as he went about developing his own.

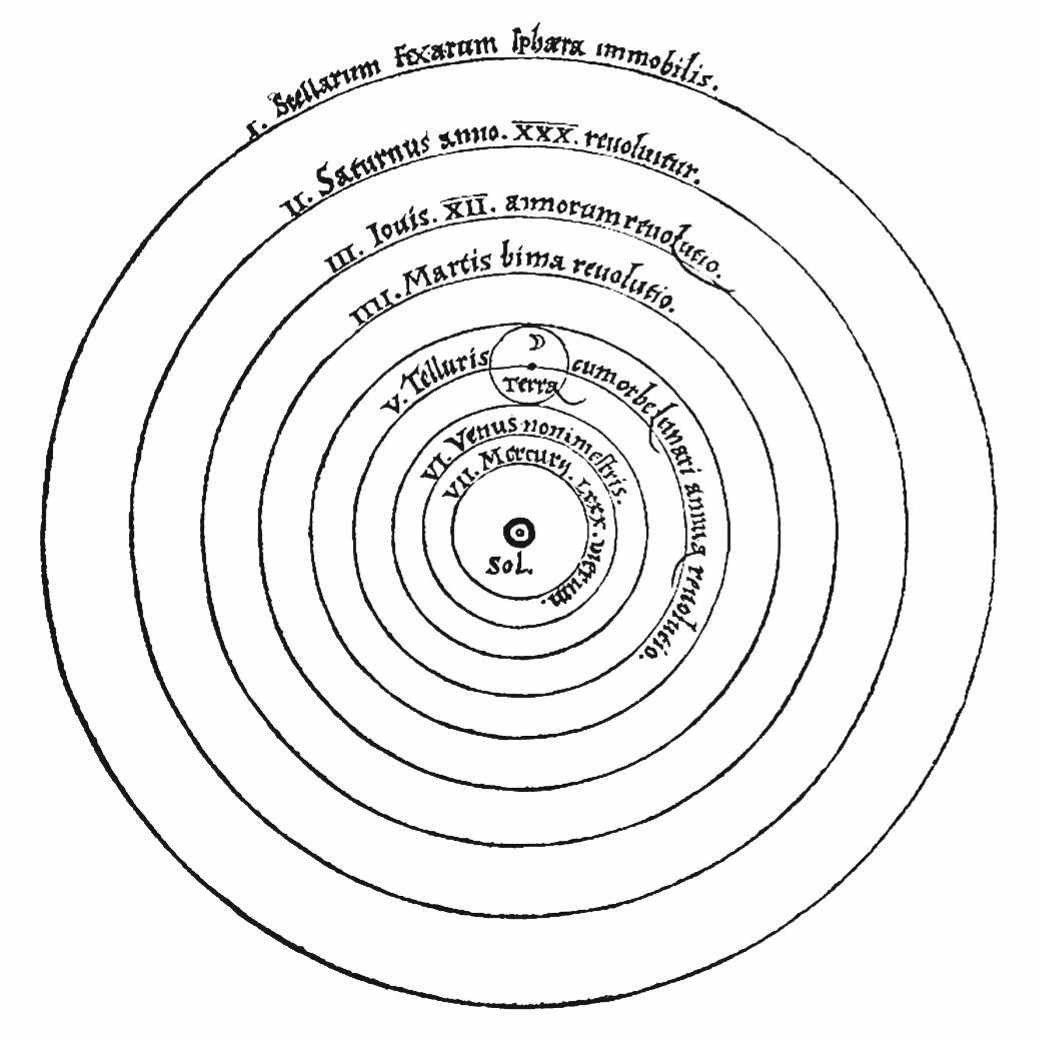

Due to a lack of primary sources, historians can only speculate on how Copernicus arrived at the heliocentric model. However, it’s generally agreed it was a combination of observing planets in the early 1500s at his observatory in Frombork, and careful analysis of planetary models, including those from the Islamic world, coupled with a philosophical desire for simplicity. All those epicycles needed to account for retrograde motion were getting in the way of a neat, simple, useful mathematical model.

As Commentariolus circulated among his acquaintances, Copernicus carried on with his work, collaborating with other Kraków astronomers on the observation of eclipses. He took part in discussions about the reformation of the Julian calendar, which would eventually lead to the adoption of the Gregorian calendar we use today. He was beginning to develop a reputation too as distant and aloof, a scholar with a dark and questionable secret theory – at least that’s how he was caricatured in the play Morosophus (‘The Foolish Sage’).

By 1532 Copernicus had finished writing De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (‘On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres’), but was still not ready to publish. A year later, his friend Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter, secretary to Pope Clement VII, explained Copernicus’s theory to the Pope and two cardinals, and they found it most interesting. Although still not published, more educated people around Europe began to learn about the theory.

In 1543 Copernicus was eventually persuaded to publish, but he did so extremely cautiously. He dedicated the book to Pope Paul III, and his printer Andreas Osiander wrote a preface explicitly explaining that the model should be seen as a mathematical tool or model, rather than a representation of what was actually there. The book was written in Latin, the language of the rich, educated elite and was not accessible to the general population.

Copernicus’s precautions, and longstanding association with the church, paid off. Not everyone was convinced, but disagreements were mathematical and scientific rather than theological. Tycho Brahe, the Swedish astronomer (born not long after the book came out), found Copernicus’s model unsatisfactory and came up with his own, which fits the same data but keeps Earth at the centre.

In his, the planets orbited the Sun and the Sun and Moon orbited Earth. Though Brahe was pleased to have kept Earth at the centre of the Universe, his model was not to last. Observations and theories by his assistant Johannes Kepler, and later still Galileo Galilei, showed Copernicus’s model to be a much better fit.

Galileo famously received a very different reception to Copernicus, and there were several reasons for this. Galileo made much less effort to appease or appeal to the church than Copernicus. He did not try to present his heliocentric ideas in a way they would find reassuring, nor did he limit his readership by only writing in Latin. The church was also much less sure of its absolute power by the 1600s, given the rise of Protestantism, and less willing to tolerate criticism.

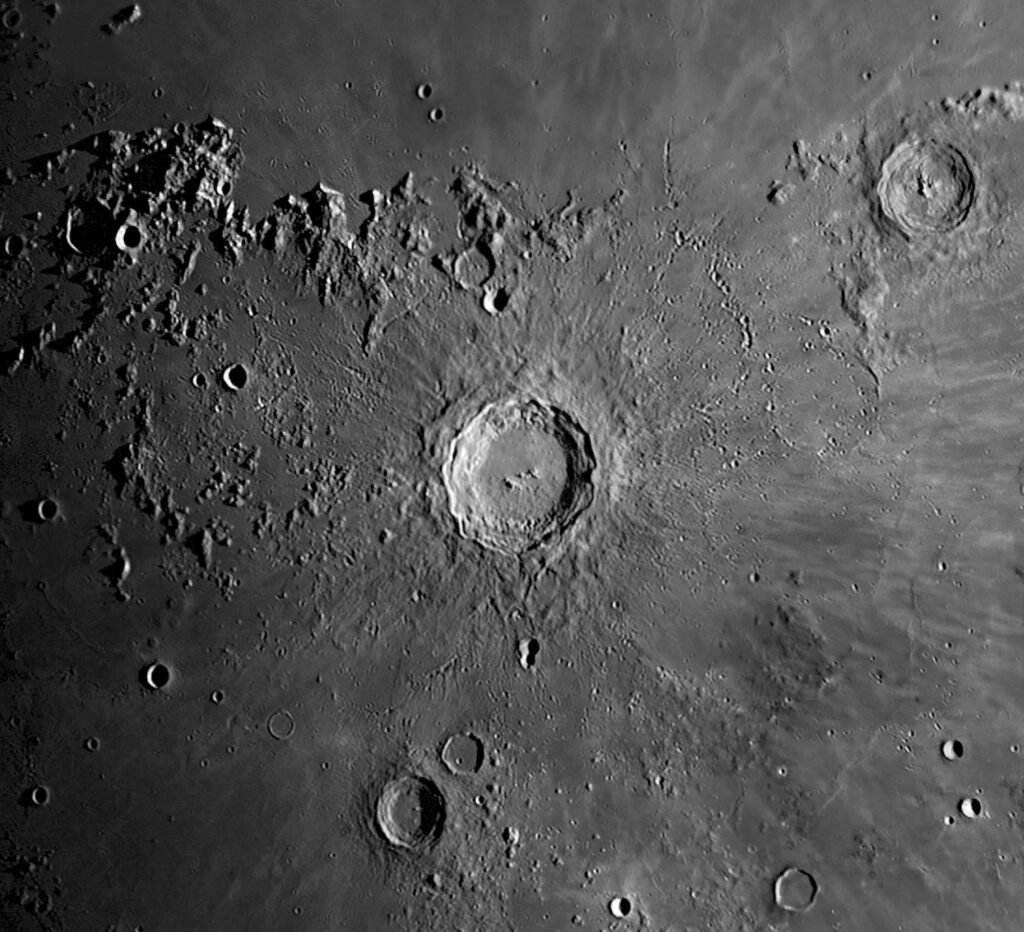

Today, Copernicus’s name is synonymous with astronomy. His face has been on banknotes and stamps and he features in every timeline on astronomical history. He even has a crater on the Moon named after him. And that’s not forgetting the European Space Agency’s Copernicus programme, which helps us better understand and mitigate the effects of climate change by observing Earth from space. In his own time Copernicus was able to present challenging scientific ideas to the powers that be in a peaceful and productive way. Perhaps through ESA, his namesake will be able to do the same.

Timeline: A life of revolutions

The story of Copernicus’s life has been pieced together from limited sources. Only 17 of the letters he wrote in his lifetime survive, and he left little by way of personal papers. Instead, we have manuscripts and published editions of his printed works as well as public records of births, deaths and appointments.

1473

Copernicus is born, of German parents, in a city in northern Poland, Torun.

1491

Enrolling at the University of Kraków, his studies include mathematics.

1495

His uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, arranges a church admin position for him.

1496

Copernicus goes to the University of Bologna, to study canon (religious) law.

1497

He observes an occultation, as the Moon eclipses the star Aldebaran.

1501

He goes to the University of Padua to study medicine (with astrology)

1503

In Frombork, Copernicus works for his uncle as a physician.

1514

Copernicus writes Commentariolus (‘Little Commentary’).

1532

He writes his landmark De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.

1533

His ideas are presented to the Pope who expresses an interest in them.

1543

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is published.

1543

Copernicus dies in Frombork, aged 70, and he is buried in the city’s cathedral.

1583

Tycho Brahe puts forward his alternative model of the Universe.

1610

Galileo Galilei publishes his support of the Copernican model.

Emily Winterburn is an astronomy historian and author.