Taking nightscapes and star trails with a DSLR camera is a great way to get started in astrophotography. Stuart Atkinson gives his best tips for beginners

The cameras that are built in our smartphones are incredible pieces of technology. Today, many people use their smartphone cameras to capture images of the night sky using ‘Night’ or ‘Low Light’ settings, or even dedicated apps. These are great for photos of bright things, such as lunar haloes, planetary conjunctions and bright comets, but eventually anyone wanting to take astrophotos of constellations, nebulae and other celestial delights will have to consider a better option. They need to bite the bullet and buy what many people still consider ‘a proper camera’ – a DSLR, or Digital Single Lens Reflex camera. The only problem is, then they have to use it…

This feature is going to take you by the hand and lead you gently through the minefield of taking and processing your very first astrophotos. After that, you can start experimenting with settings and composition to make your photos even better.

There’s no better time to make a start, as the Astronomy Photographer of the Year Awards 2023 has just opened for entries. The awards have a special prize for newcomers who have only recently started taking astrophotos – perhaps one of yours could be the one to take home the prize.

But first, let’s get started with your first photo!

Setting up your equipment

Getting the right kit is key to getting a good first photo

What will you need to take your first astrophoto with a DSLR? Obviously the most essential thing is a DSLR, and we’re going to assume you already have one of those! The make is irrelevant, they all do the same job, which is to collect light on a sensor chip that is turned into an image. You’ll also need a memory card in your camera. This sounds obvious but trust me, you don’t want to be standing in the middle of a field in the dark and see the words ‘No Memory Card In Camera’ appear on your screen because you left it at home – not that I’ve ever done that, of course!

If you use your DSLR for daytime photography you’ve probably got several lenses, but which one should you use for taking your first astrophoto? The 18–55mm ‘kit lens’ or standard 50mm lens that came with your camera will be fine. Don’t use anything ‘bigger’ than 50mm yet.

You will need to have a good tripod to mount your camera on, because (despite what some people will tell you) you just won’t get the same results from pushing your camera down into a bean bag or rolled-up jumper plonked on the top of your car. A remote shutter release is highly recommended, but not essential. Take along the red flashlight or head torch you use when you’re out stargazing. If you don’t have one, install a ‘Red Light’ app onto your phone.

Lastly, but very importantly, you’ll need a good location to take your photos from. If you’re restricted to your back garden that’s fine, you can still take pictures, but if you can get away from all the streetlights, security lights and illuminated shop signs to a dark-sky site, those pictures will be much better.

Taking your first astrophoto

Bright constellations like Orion are a great target to get started

One of the aspects of astrophotography that newcomers find most difficult is focusing their camera. It’s easy photographing a friend’s wedding reception, or your sleepy kitten in the daytime, but the first time you try to focus your camera on the night sky you’ll probably want to throw it into the bushes in frustration. Finding focus is actually quite easy once you know how. First, take off the lens cap (personal tip here: get into the habit of always putting lens caps into your left pocket, think ‘Left for Lens’, so you won’t forget where they are). Next, set your camera focus to ‘Manual’ instead of ‘Auto Focus’ and then point it at a streetlight or a light on the side of a distant building – not a star. Focus on it roughly using the viewfinder, then use the ‘Live View’ feature on your camera screen to fine-tune the focus until it’s sharp. Now swing your camera towards a bright object in the sky – perhaps the star Sirius, or the planet Mars, both of which will be prominent as you read this – and use ‘Live View’ to focus as sharply on it as you can. After that, leave it alone.

Next, aim your camera towards the constellation of Orion, centred roughly on Orion’s Belt. Don’t worry about framing, or foregrounds, you’re just trying to photograph some stars this very first time. When you can see stars clearly on your camera screen, set its ‘Mode’ to ‘Manual’ by turning the appropriate dial, or selecting it from a ‘Settings’ menu. Next, set your camera’s ISO (which mimics the film speed of film cameras) to 1600. Then set the ‘Exposure Time’ to 15 seconds if you’re using a wide-angle kit lens, or 4 seconds if using a standard 50mm lens.

There’s just a few more tweaks and you’ll be ready. Set a ‘Time Delay’ – around 3 seconds or 10 seconds, depending on the make of your camera – as this will give a few seconds to reduce vibrations after clicking the camera’s shutter, keeping your stars as points of light instead of squiggles. Alternatively, if you have one, use a remote shutter release to take the picture without touching the camera.

Finally, set the ‘Image Format’ to ‘RAW’ if you want, but it’s not essential at this early stage, no matter what some people may tell you. RAW format images record more information, so give better processing results, but it’s perfectly fine to just stick to JPEG format on the first night if you’re more comfortable with that (or you just forget).

Then take a deep breath and push the button to take your first photo.

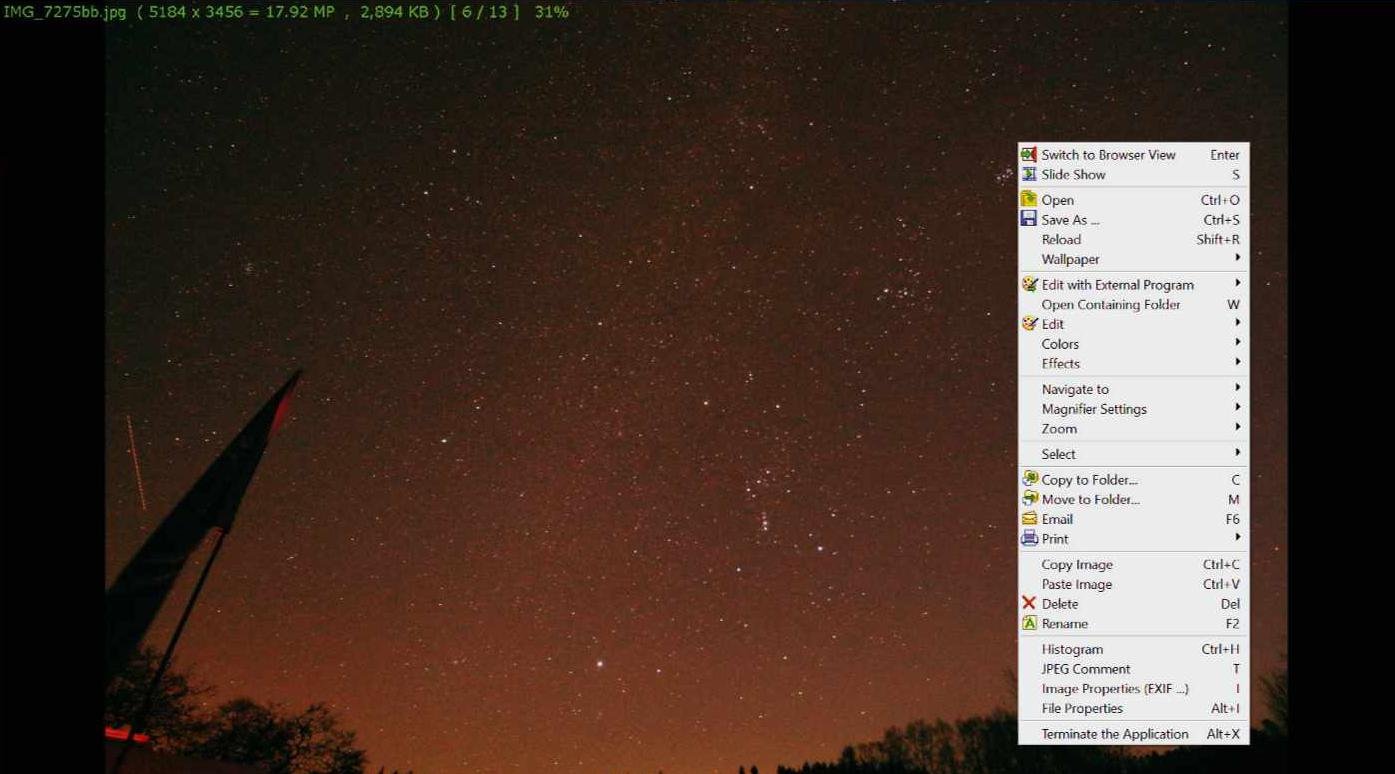

It will feel like time has stood still as your camera drinks in all the starlight, but eventually you’ll hear a click telling you it’s finished. If everything worked you’ll have just taken your first astrophoto, so take a look on the preview screen. If a wide-angle lens was used all of Orion will be on it, while a 50mm lens won’t quite get all of it. If it’s a little wonky, don’t worry, it doesn’t matter – this is just your first try. Just look how many more stars are on it compared to pictures taken with your phone camera, and how colourful they are. How cool is that? Congratulations!

Taking better photos

If your first attempt doesn’t work, there’s plenty of things to try

There are several common problems that might crop up on your first astrophoto. If your image is too dark, increase either the ISO or ‘Exposure Time’. If your image is too bright, decrease either the ISO or ‘Exposure Time’. If your stars look like squiggles, something moved during the exposure, so tighten everything up, especially on your tripod. If your image looks orange, change the ‘White Balance’ from sunlight (a ‘Sun’ symbol) to artificial light (usually a symbol that looks like a ‘Lightbulb’ or a strip light), which will get rid of the orange cast produced by light pollution.

Now try again – your second photo should be better than your first.

Then keep going. Try a variety of different ISOs and exposures, just to see the difference that changing these basic settings makes. When you have found a selection of settings that collectively give you good images, stick to it. Leave Orion and try imaging different parts of the sky, maybe Mars, or Sirius, or Cassiopeia – it doesn’t matter which. You’ve done the hard part, now it’s time to just experiment and have fun!

Processing your first image

A little experimentation can give great results

Having taken your first images, you need to get them off your camera and into a computer if you want to see them, improve them and share them with others. This is called processing and getting started can be quite daunting, so we’re just going to look at the absolute basics here. Follow these, and you’re on your way to creating incredible astrophotos. You will need:

► A USB card reader to insert into your computer, or its card-reading slot

► The memory card from your camera

► Image-processing software on your laptop

Step 1

Remove your camera’s memory card and insert it into your computer’s in-built card reader, or an external one. Find the relevant external drive folder and click on it to locate your images. We recommend that you change the settings on your computer so images show as pictures, not just meaningless file names.

Step 2

Open your image-processing software and import one of your images. On the screen your image won’t look as bright or as detailed as it did on the back of your camera, but don’t panic! You were looking at a high-contrast version, in the dark, on a bright screen. Once enlarged it will look less punchy, but the processing will change that.

Step 3

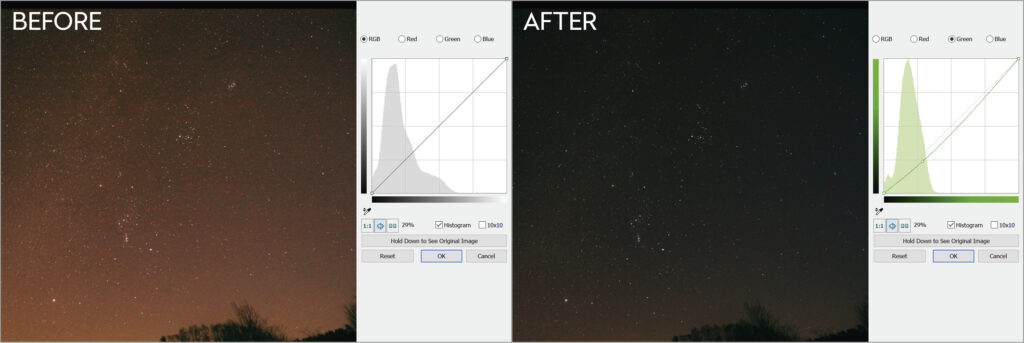

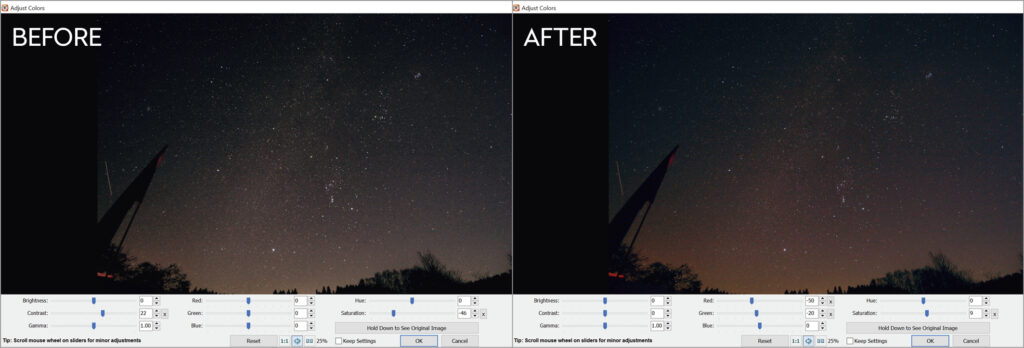

First, use the ‘Curves’ function to change how your image looks. Experiment by moving the curve around to adjust the brightness and contrast until it looks better. Don’t go overboard – remember that less is more when it comes to astro image-processing. You can always undo your work if you go too far.

Step 4

Use the ‘Saturation’ function to change how colourful your image looks. If the colours of the stars are too garish you can reduce that, or if they are too bland you can boost them. But again, don’t go mad or you can end up making the stars too bright and blown out.

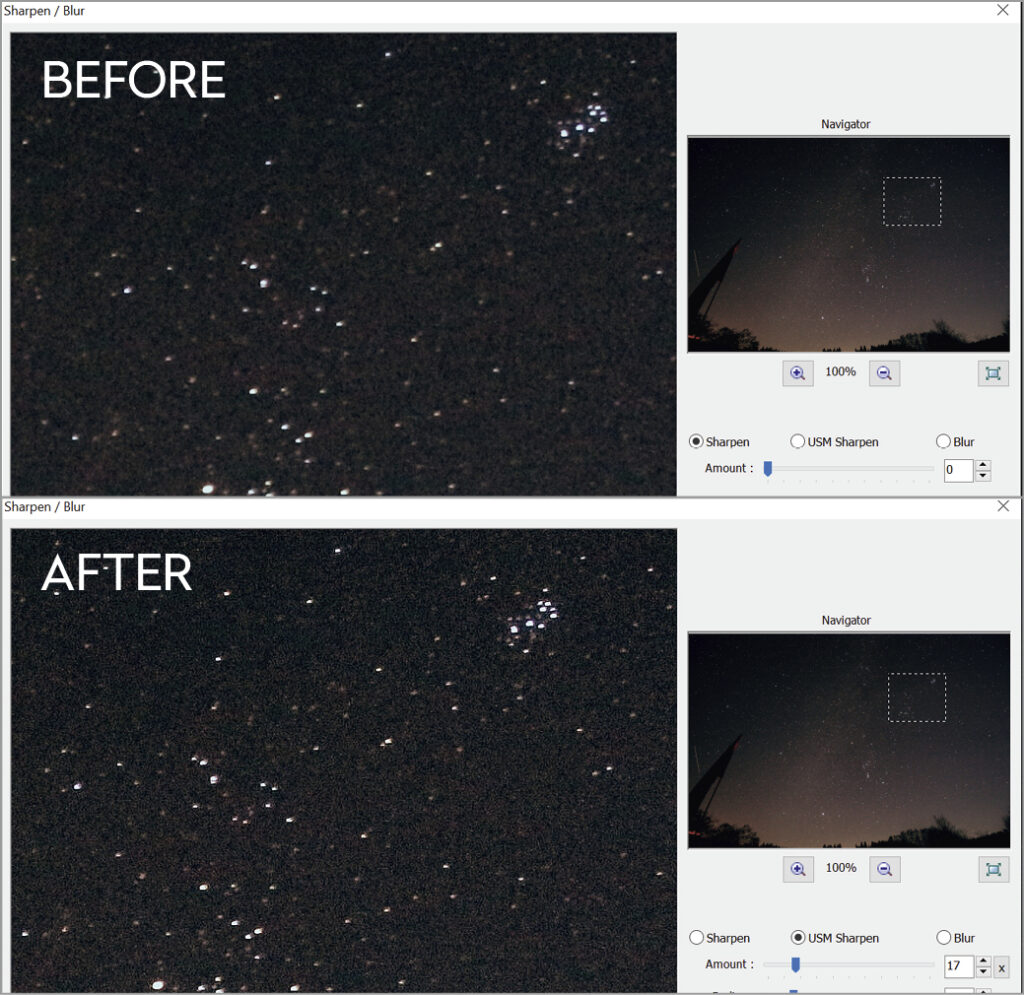

Step 5

Use the ‘Sharpen’ function to make your image clearer, especially if your focus wasn’t as sharp as you thought it was. If you used RAW format when shooting, your images will look a lot cleaner than JPEGs, but at this stage that’s not too important.

Step 6

When you have a processed image you’re happy with, create a new folder on your computer – put the date you took your images in the title to help you find them again – and export your image into it. Use ‘Save As’ to create a new file with its own name, leaving the original on your memory card for now. You might want to go back to it later.

Stuart Atkinson is a lifelong amateur astronomer and author of 11 books on astronomy.