Our experts examine the hottest new research

CUTTING EDGE

Ancient explosion was a rare supernova

Astronomers have puzzled over the bright event for centuries

Over 840 years ago, in August 1181, Chinese and Japanese astronomers saw a new star suddenly appear that remained visible for 180 days. We now know this was the violent death of a massive star, a supernova, and the 1181 event is one of only a handful to ever have been seen with the naked eye.

Now astronomers have started looking at the site of the supernova, in the modern constellation of Cassiopeia, in the hope of finding a remnant. Radio searches, which attempted to uncover a pulsar, failed to find anything suitable, but citizen scientist Dana Patchick, combing through data from numerous earthbound surveys, as well as the infrared WISE satellite, found an unusual circular nebula which surrounds a bright central star around 8,000 lightyears from Earth.

Studies of this new object have shown that the bright region is a shell of gas expanding at a rate of more than 1,000km per second. Projecting backwards, this gives an age for the object of nearly a thousand years, fitting perfectly with the recorded supernova. Another new paper, with deep images of the nebula, shows its structure, with filaments pointing away from the central star, which must therefore be the source of the gas.

But if this is a supernova remnant, then what is the central star? A supernova should produce a dense neutron star, or a black hole. But neither of those should shine brightly, whereas this observed star is more than four times as luminous as the Sun. It’s detected not only in the infrared, but also in ultraviolet and in X-ray observations, which reveal a temperature of 200,000° Celsius. Spectra tell us that it is made of (mostly) carbon and oxygen, with none of the hydrogen and helium that accounts for most of the mass in the Sun and other main sequence stars.

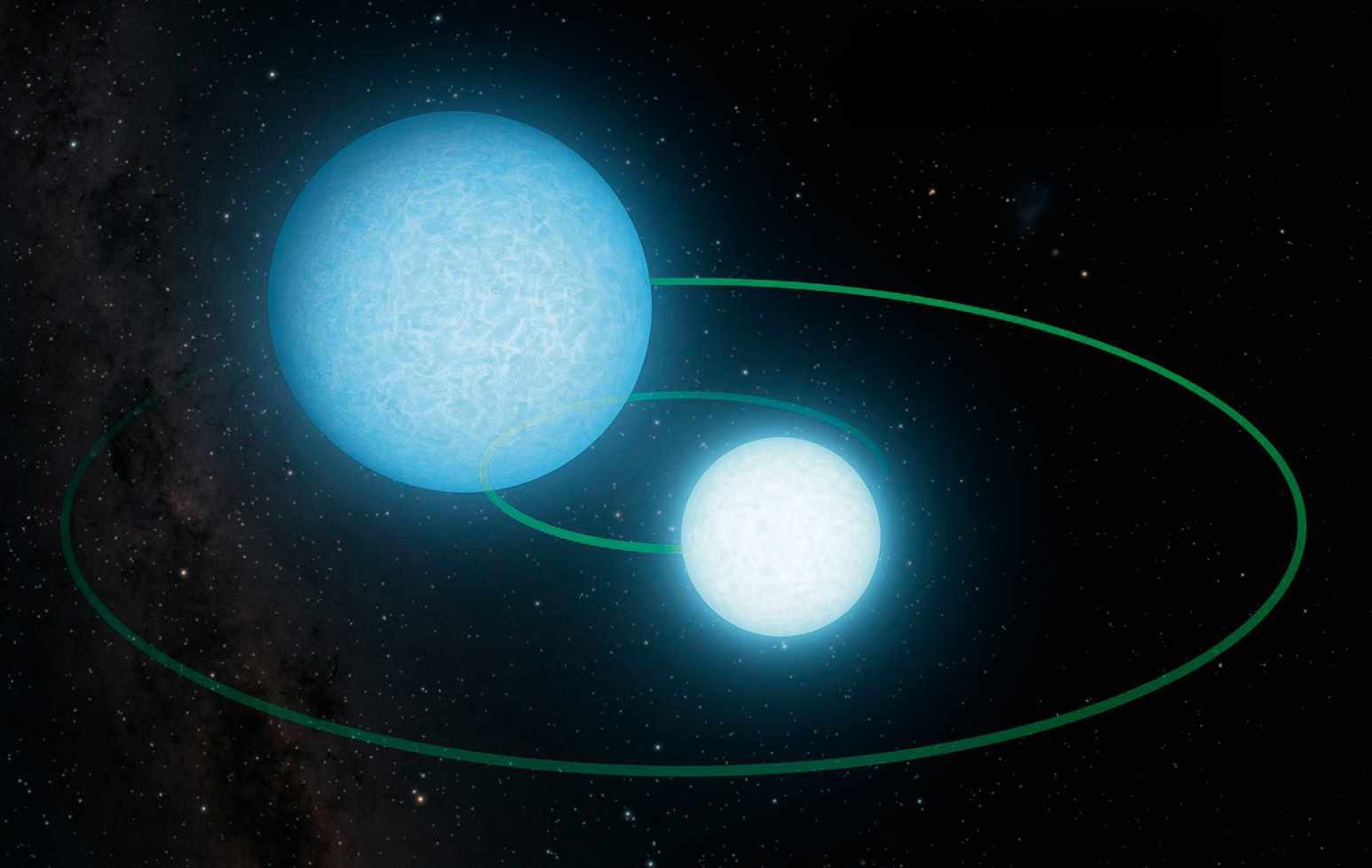

“In a Type Iax, both stars are white dwarfs, and the supernova is produced when the two collide and merge with each other”

It looks, in fact, like a hot white dwarf, but such objects are normally formed from the death of stars far less massive than those that go supernova. The paper by Bradley Schaefer resolves this conundrum by claiming the 1181 event was an example of a little-understood, rare class of supernova: a Type Iax.

Type Ia supernovae are typically caused by the interaction of a white dwarf with a binary companion. In a normal Type Ia, the white dwarf steals matter from an orbiting normal star until this piled-up material ignites, blowing the host dwarf apart. In a Type Iax, both stars involved are white dwarfs, and the supernova is produced when the two collide and merge with each other.

In this case, it seems we can explain everything that’s been observed if we invoke a collision between two white dwarfs, one rich in carbon and oxygen, and the second in oxygen and neon. Crucially, such an event would have left only a single central star with no companion, exactly as observed. If this is the end of the search for the ancient supernova’s remnant, it will be the beginning of a new scientific quest. This is only the fifth time we have found the remnant of a supernova that was also seen in the sky, and it may help us understand these rare and spectacular events.

Prof Chris Lintott is an astrophysicist and co-presenter on The Sky at Night.

Chris Lintott was reading The Path from the Chinese and Japanese Observations of Supernova 1181 AD, to a Type Iax Supernova, to the Merger of CO and ONe White Dwarfs by Bradley E Schaefer

Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2301.04807