New astronomy and space titles reviewed

Comet Madness

Richard J Goodrich

Prometheus Books £21.99 HB

While the appearance of a bright comet in today’s skies can invoke great excitement, history informs us that such a spectacle was more likely to provoke quite a different response – one of foreboding.

In a comprehensive overview of the literature that documented these apparitions at the time, Comet Madness offers a thorough sweep through the musings of those foretelling the reasons behind a comet’s appearance and the consequences likely to befall the world from its fiery presence.

Author and historian Richard J Goodrich relates how civilisations reacted to the foretelling and subsequent sighting of a new arrival in the heavens. With the use of intriguing and often whimsical comet-based quotes to head up each chapter, he neatly catalogues in a flowing dialogue how centuries of archive material generally paint a desperate picture heralded by a comet’s presence, of widespread fear among all walks of life.

Goodrich charts the achingly slow process humankind grappled with to understand comets, with huge swathes of the public for much of the time refusing to believe that they were anything but doom-laden toxic invaders that could only spell death and misery for the inhabitants of Earth. However, where there’s a crowd there’s business, and the author also details the unscrupulous characters out to make money off the back of such impending dread, with ‘comet pills’ and ‘comet insurance’ available for purchase.

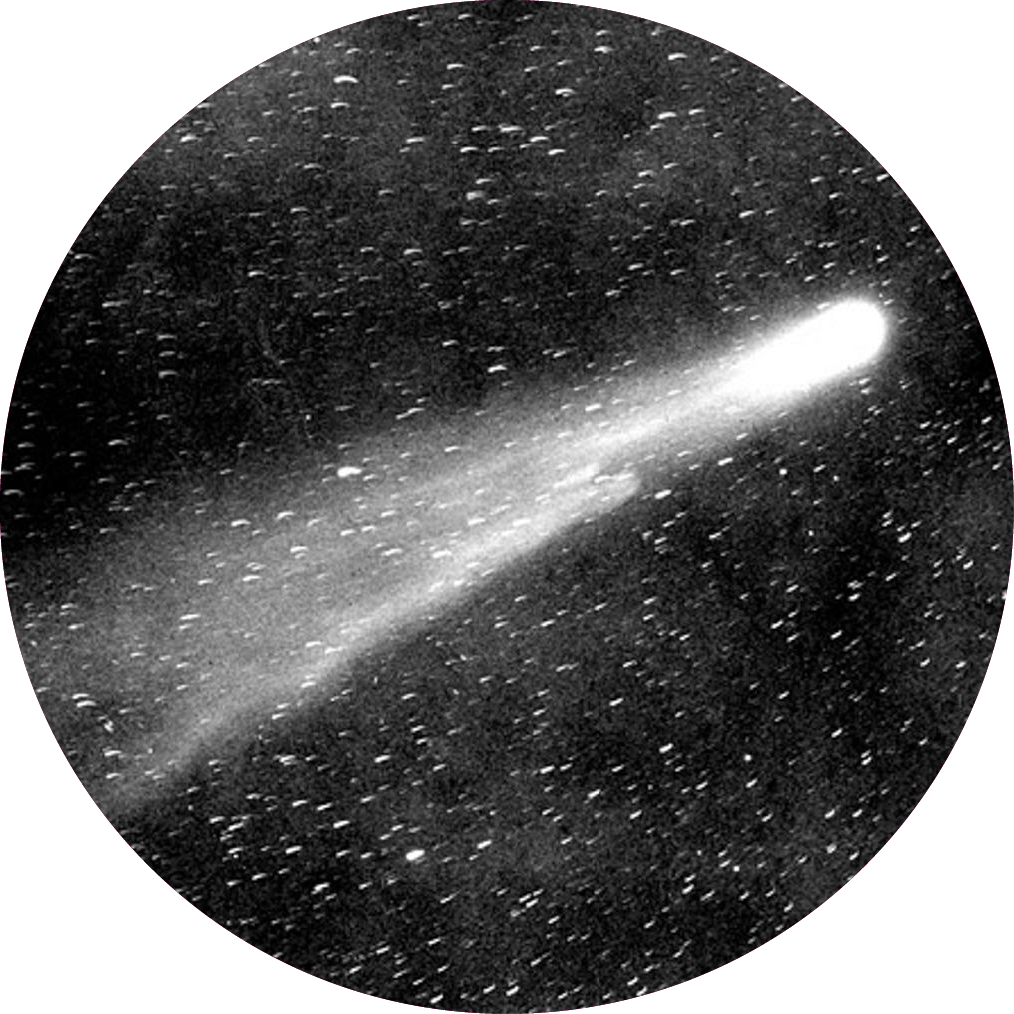

In a solid and engaging read, Goodrich also captures the many-sided arguments presented as scholars wrestled to conclusively explain the arrival of ‘hairy stars’. Notably, and because of the amount of archive material available from the period, the book focuses on the return of Halley’s Comet in 1910, including the immense influence on both media and public of French astronomer Camille Flammarion, who ignited fears by declaring that the comet’s tail would wipe humanity off the face of the Earth with its toxicity.

Featuring a wealth of historical information, from early Chinese archives to latter-day records, Comet Madness generates a collectively sound reflection of how such events impacted upon the human psyche, delivering an enjoyable amble through humankind’s relationship with comets.

Interview with the author

Richard J Goodrich

Why do comets capture our imagination?

Comets are unlike any other celestial object. They flicker into existence, grow until their silver tails stretch across the star field, and slowly fade. Following orbital paths that can take a thousand years to complete, they are silent voyagers in the interstellar darkness beyond the borders of our Solar System.

How did ancient astronomers view comets?

Before Edmond Halley, they were widely regarded as a message from the gods. For Chinese astronomers their disturbance of heavenly harmony symbolised divine displeasure, foreshadowing the fall of emperors. Political upheaval was a common interpretation in the West: Halley’s Comet appeared before the Norman invasion and the fall of Constantinople. Reformation-era Christians believed they augured God’s displeasure with their theological adversaries, and stood as indisputable signs that the apocalypse was at hand.

What are the most ridiculous stories from the 1910 Halley’s Comet hype?

An Arizona Daily Star reporter allegedly interviewed a travelling Assyrian sage named Reetsmub. This descendant of Sennacherib said an ancient tapestry predicted the comet’s appearance at the birth of Christ and the destruction of Earth in 1910. Amateur astronomer Edwin Naulty argued the comet’s head was a lens that concentrated sunlight into a burning tail that would cause devastation on Earth.

A Day in the Life of an Astronaut, Mars and the Distant Stars

Mike Barfield, Jess Bradley

Michael O’Mara £10.99 PB

Any book that introduces children to the night sky is to be encouraged. This book uses an engaging comic-book format while managing to pack in an incredible amount of information.

Its scope is comprehensive, covering our neighbours in the Solar System and the missions we have sent to visit them. It goes onward and outward to the stars, galaxies, nebulae and black holes. It tells the history of our exploration of the cosmos, including the Space Race, the Apollo missions, and past and future space stations. It also manages to explain complex concepts like gravity, dark matter and dark energy. All this is done in cartoon strips, packed with anthropomorphised stars, planets and asteroids, zooming about shouting ‘Wheee!’ a lot and bumping into things. The jokes don’t get much more sophisticated than that, though I did like the solar wind explained as Sun farts.

The book may have benefitted from trying to cram less in, giving more space for more comic-book fun. Some missions and telescopes barely get mentioned, so there is lots of scope for further reading.

It may also have been good to have a library of high-quality space images to show alongside the book. Cartoon planets, moons, nebulae and galaxies, even with eyes and mouths, may be cute and friendly, but they miss the wow factor of the real thing.

Nevertheless, this is a fun and entertaining introduction to space for young children, and that is no bad thing.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Universe

Jorge Cham, Daniel Whiteson

John Murray £10.99 PB

Out of the 20 questions in this book, I’ve wondered about nearly all of them, usually after watching a sci-fi film. Why can’t we teleport? Will an asteroid hit Earth? Why can’t we travel back in time? And why was Biff such a bully?

Okay, that last one isn’t in the book, but I bet that physicist Daniel Whiteson and researcher-turned-cartoonist Jorge Cham would have a funny, intelligent answer for us if it was. Each chapter tackles a different question, though a single answer isn’t guaranteed. Some require a little lenience in the definitions of possible and impossible – travelling through time might not be impossible, albeit with very strict parameters; if general relativity isn’t right about black holes, then it could be possible to survive one.

Cham and Whiteson’s clever analogies help explain some of the concepts, but I did have to Google a phrase every now and then. Perhaps the target reader has a little more knowledge, but I would have appreciated a description of things like quantum states, or a refresher on the laws of physics.

Still, this book is full of fun snippets of information that you’ll want to share with others. It also has moments of awe and of sensitivity. “Is there another you?” may seem more like a question for philosophers than physicists, but it’s incredible to think a quadrillion decisions had to occur since the Big Bang for you to exist right now. That’s a quadrillion and one, I suppose, if you count your decision to read this review.

The First City on Mars

Justin B Hollander

Springer £24.99 PB

“There will be towns and then cities on Earth’s Moon and on Mars sooner than you think,” predicts Hollander in this fantastic book on engineering a future for humans on Mars. And if that’s true, he argues, there is much to consider to ensure the survival of our future interplanetary citizens.

The First City on Mars is a book about space architecture in the context of planning cities on a planet with 38 per cent of Earth’s gravity and a thin atmosphere of carbon dioxide. Such environments require new perspectives in urban planning, theorises Hollander, to ensure the survival of thriving communities living in such inhospitable environments. Drawing on lessons learned from older civilisations and their urban planning methods, the author lays out past and present habitat designs for off-Earth living.

He draws on the experiences of extreme environment communities on Earth, such as the Antarctic. There’s an interesting summary of Moon exploration, and recent lunar habitat and building design proposals; his review of the imaginative and futuristic designs of off-world city layouts as detailed by the O’Neill cylinder and Bernal sphere space settlements is particularly appealing. The final chapters summarise key findings from the extensive research previously presented, and Hollander proposes a compelling and enticing city design for Mars.

The book is well-written, clear and concise, supported with impactful visual content and imagery. Perhaps most importantly, it has universal appeal beyond that of engineering or architecture specialisms. Hollander makes a strong argument to dream big and plan now for a future in the first Mars city.