Patrick Moore

A PASSION FOR SPACE

On the 100th anniversary of his birth, we look back on the life of Britain’s best-loved amateur astronomer

Patrick Moore did more than anyone in history to get people interested in the stars. As the face of The Sky at Night, he introduced millions to the wonders of the night sky and in the process set a television record, by becoming the world’s longest-serving presenter on the same programme.

Thanks to his passion for astronomy, ruffled appearance and slightly eccentric manner, Patrick’s persona made him a celebrity among the general public and a household name in the UK, where he was the only amateur astronomer most people had heard of, while his books and magazine articles gained him recognition the world over.

Alfred Patrick Caldwell-Moore was born on 4 March 1923, the only child of Captain Charles Trachsel Caldwell-Moore MC, who had served in the army, and Gertrude Moore (née White), who trained as an opera singer in Italy.

Patrick grew up in Sussex – first in Bognor Regis and later in East Grinstead. He went to prep school for one term when he was eight, but his formal schooling was limited by the heart problems he suffered up to the age of 16. While this seemed to have put paid to any thoughts of going to Eton College and the University of Cambridge, it did leave him plenty of time for other pursuits.

He could play the piano by the age of eight and had composed his own Viennese waltz by the age of 10. At 13, a chance win on the football pools enabled him to buy a xylophone. The following year he gave a solo performance on it at a theatre in East Grinstead. Music was to play a big part in his later life, and he once said that one of his biggest regrets was not taking it more seriously.

Patrick’s interest in astronomy started early. Hooked at the age of six, after reading GF Chambers’s 1898 book The Story of the Solar System, he resolved to learn a new constellation each night and bought a pair of binoculars to explore the heavens. Such was his new-found passion that a family friend proposed him for membership of the British Astronomical Association (BAA). At the age of 11, he became its youngest member and would go on to become its president 50 years later.

Early promise

Patrick’s first big break arrived in the form of WS Franks, an astronomer who operated the privately owned Brockhurst Observatory in East Grinstead. Patrick was just 14 years old when he was asked to take over the running of the observatory after Franks’s death. When he wasn’t showing invited guests the wonders of the night sky, he used its 6-inch telescope to study the Moon.

His observations of lunar craters were so detailed that he wrote them up in a paper and presented them at a BAA meeting. It was the start of Patrick’s long obsession with the Moon. Not long afterwards, another trademark quirk was born. When an optician told him his eyesight was lacking in one eye, he insisted on wearing a monocle rather than a frame with one blank lens.

Despite the heart problems that beset him, he passed school exams with the help of tutors and was due to take up a place at the University of Cambridge when the Second World War broke out. He joined the RAF, despite lying about his age (he was only 16) and getting a friend to stand in for him at his physical examination. He rarely spoke about his wartime experiences, but it is known that he was a navigator on bombing raids to Germany, rising to the rank of flight lieutenant. Astronomy know-how came in handy, enabling him to navigate by the stars using a sextant when the night skies were clear.

His deepest scar from the war was the death of his fiancée Lorna, killed by a German bombing raid in 1943. Such was the pain of the tragedy that he never entered into another relationship. He once commented in an interview for This is London magazine, “I would have liked a wife and family, but it was not to be.” He did, however, take several godsons under his wing – some being the children of late friends.

After the war, he decided to work as a teacher in order to save up enough money to take up his place at Cambridge. He worked first at a prep school for boys in Woking and then at Holmewood House in Tunbridge Wells. It was while teaching that he set up a 12.5-inch reflecting telescope at his home in East Grinstead and recommenced his studies of the Moon.

His in-depth lunar knowledge was to serve him well when it came to establishing a new career. As a boy he’d learned to type by copying a 60,000-word book about the Moon by WH Pickering. In 1952, he wrote his own book, Guide to the Moon, later renamed Patrick Moore on the Moon, on a 1908 Woodstock typewriter. The book was such a success that it was reprinted before it was even published, and ran to eight subsequent editions. With his writing career taking off, he made the decision to leave Holmewood House and penned a series of science fiction novels with titles such as The Master of the Moon; hundreds of books and countless newspaper and magazine articles followed.

By the mid-1950s, Patrick was no stranger to appearing on TV and radio programmes as an expert astronomer. One television appearance was to prove particularly fortuitous. During one of the regular outbreaks of flying saucer sightings, he was asked to argue the case against alien visitations in a live BBC TV debate. The programme’s producer, Paul Johnstone, was impressed by Patrick’s performance and soon sounded him out about being the frontman of a new astronomy TV show in development, called Star Map.

The life of Patrick Moore

1923 Patrick is born on 4 March. Family moves to Bognor, West Sussex

1929 Hooked on astronomy after reading The Story of the Solar System

1931 Acquires a 1908 Woodstock typewriter and learns to touch-type

1934 Becomes youngest member of British Astronomical Association

1937 Takes over the privately owned Brockhurst Observatory

1939 Signs up for RAF, foregoing a place at the University of Cambridge

1940 Meets Albert Einstein and Orville Wright in New York

1943 Fiancée Lorna, a nurse, dies when a bomb hits her ambulance

1945 Returns from RAF service; family moves to East Grinstead

1945 Joins the teaching staff of Holmewood House prep school, Kent

1946 Observes mare (‘sea’) on Moon’s limb; names it Mare Orientale

1953 Publication of his first book, Guide to the Moon

1957 Appears in a live televised debate on UFOs

1957 First episode of The Sky at Night is broadcast on 24 April

1959 Broadcasts first pictures of the far side of the Moon

1964 Becomes director of the BAA’s lunar section

1965 Moves to Northern Ireland to become director of Armagh planetarium

1968 Appointed to the Order of the British Empire (OBE)

1968 Leaves Armagh and sets up home in Selsey, West Sussex

1969 Takes part in a live BBC broadcast of the first Moon landing

1969 Publication of his book Moon Flight Atlas, which becomes a bestseller

1971 Appears on the Morecambe and Wise Christmas Special

1972 Covers the last Apollo mission live from Cape Canaveral

1981 His mother, Gertrude, dies at the age of 94

1984 Elected president of the British Astronomical Association

1992 Stars as the GamesMaster in Channel 4 series on video games

1995 Has Caldwell Catalogue is published in US magazine Sky & Telescope

2001 Made Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society

2001 Knighted by then Prince Charles at Buckingham Palace

2001 Receives BAFTA award for outstanding contribution to TV

2002 Helps to open the South Downs Planetarium, Chichester

2003 Publishes autobiography, 80 Not Out

2004 Sets record for longest-serving presenter on the same programme

2004 Salmonella causes him to miss The Sky at Night for the first time ever

2005 Becomes Editor Emeritus of new BBC Sky at Night Magazine

2012 Dies at the age of 89 at his home in Selsey, West Sussex

Hitting the small screen

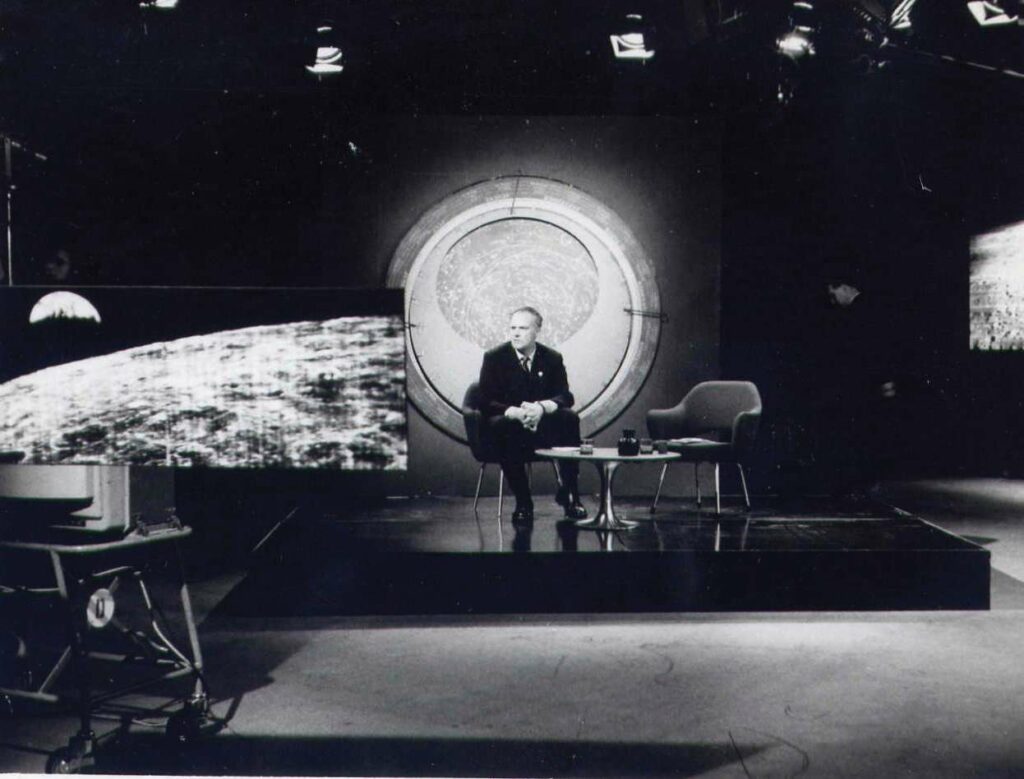

The programme first aired at 10:30pm on 24 April 1957 with a new name, The Sky at Night. The first show was broadcast live from London’s Lime Grove studio, in black and white on the BBC’s only channel, and ran for 15 minutes. Patrick later said he was grateful to the twin-tailed comet Arend–Roland – the topic of that first show – which had reached naked-eye brightness around the date of the broadcast.

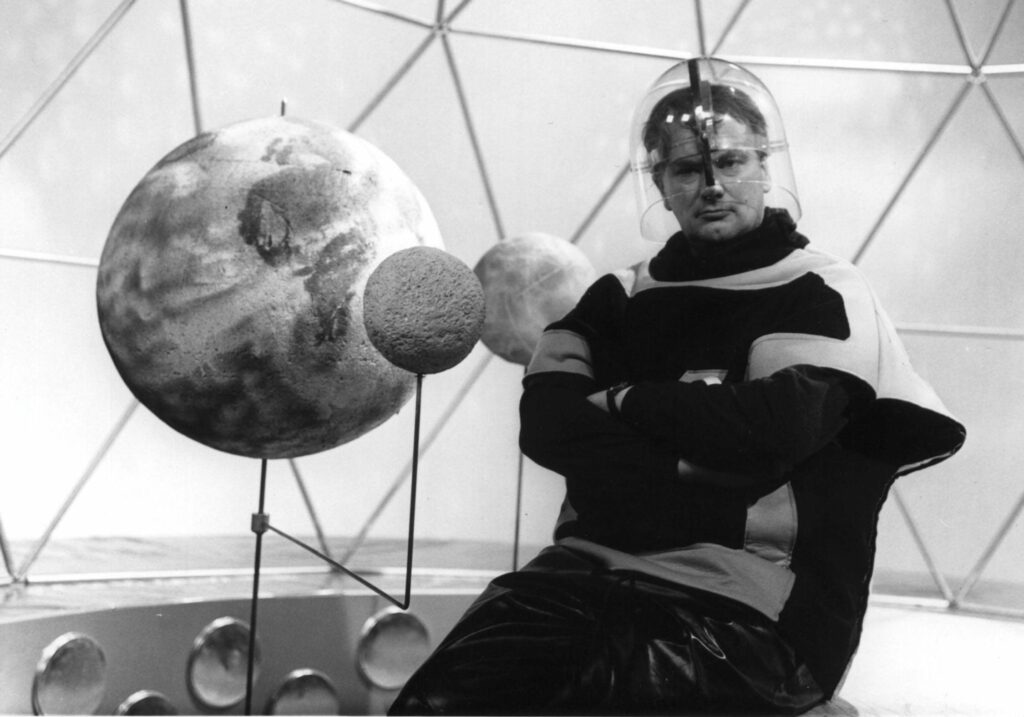

To begin with, The Sky at Night was broadcast on a trial basis, but it quickly became a monthly fixture. One factor in its early success was undoubtedly the burgeoning public interest in all things space-related. The first-ever artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched into orbit in October that same year and the pace of progress was accelerating rapidly. The Sky at Night was broadcasting at just the right time in October 1959, when the Russian probe Lunik 3 was orbiting the Moon. Patrick was able to show viewers the far side of the Moon for the first time.

With The Sky at Night occupying some of his daylight hours, Patrick continued his astronomy by night. An active member of the BAA, he was at one time director of sections devoted to observing Venus, Mercury and the Moon. And it was the Moon where his observations proved the most valuable. Patrick used sketches by himself and another amateur astronomer, Percy Wilkins, to produce a large map of the Moon’s surface. So detailed was it that the Russian space agency requested a copy to help it plan its uncrewed Lunik missions.

Patrick’s life became even busier in 1965 when he took a part-time position as director of a new planetarium being set up in Armagh, Northern Ireland. He made a big impact there, overseeing the completion of the planetarium and turning it into one of the most popular tourist attractions in the area. He left Ireland in 1968, and he and his mother bought a thatched house in Selsey, West Sussex. It was a big investment, but the Apollo 11 Moon mission the following year helped secure the household finances. Within a month of its landing on the lunar surface, Patrick’s Moon Flight Atlas had sold 800,000 copies.

Patrick was a constant presence on television during the years of the Apollo missions, covering them live with fellow presenter James Burke. The hours were long and demanding – on the night of the Apollo 11 landing, he broadcast continuously for over 10 hours. He covered the final mission, Apollo 17 – a spectacular night-time launch – from Cape Canaveral, having been studio-bound until then.

The cancellation of Apollo was far from the end of Patrick’s forays into live broadcasting. In the 1970s and 1980s, a series of unmanned NASA probes began exploring the Solar System, and he revelled in a stream of surprises, such as the lifeless surface of Mars revealed by the Viking landings in 1976, and the glorious images from the Voyager missions to the outer planets.

Aside from broadcasting, he made many other contributions to astronomy. In the 1950s, he was involved in research that attempted, unsuccessfully, to reveal a link between radio emissions and spots on Jupiter’s surface as they rotated into view. And in 1971, during the Mariner 9 mission NASA asked him to visit Johannesburg to observe dust storms on Mars to help them select areas to photograph. His activities helped amateur astronomy too. In 1995, he compiled a list of bright, deep-sky objects (clusters, galaxies and nebulae) to complement the Messier Catalogue, put together over 200 years earlier. This list, the Caldwell Catalogue, became extremely popular (see our Caldwell feature).

Inspiring a love of space

Above all, he was tireless in promoting astronomy to the public – anyone who showed an interest was given the warmest encouragement. Many professional astronomers owe their careers to the inspiration they received from a tour of his telescopes and a cup of tea with him. Members of the public would merely have to write to him to be invited to his home, Farthings, for the day.

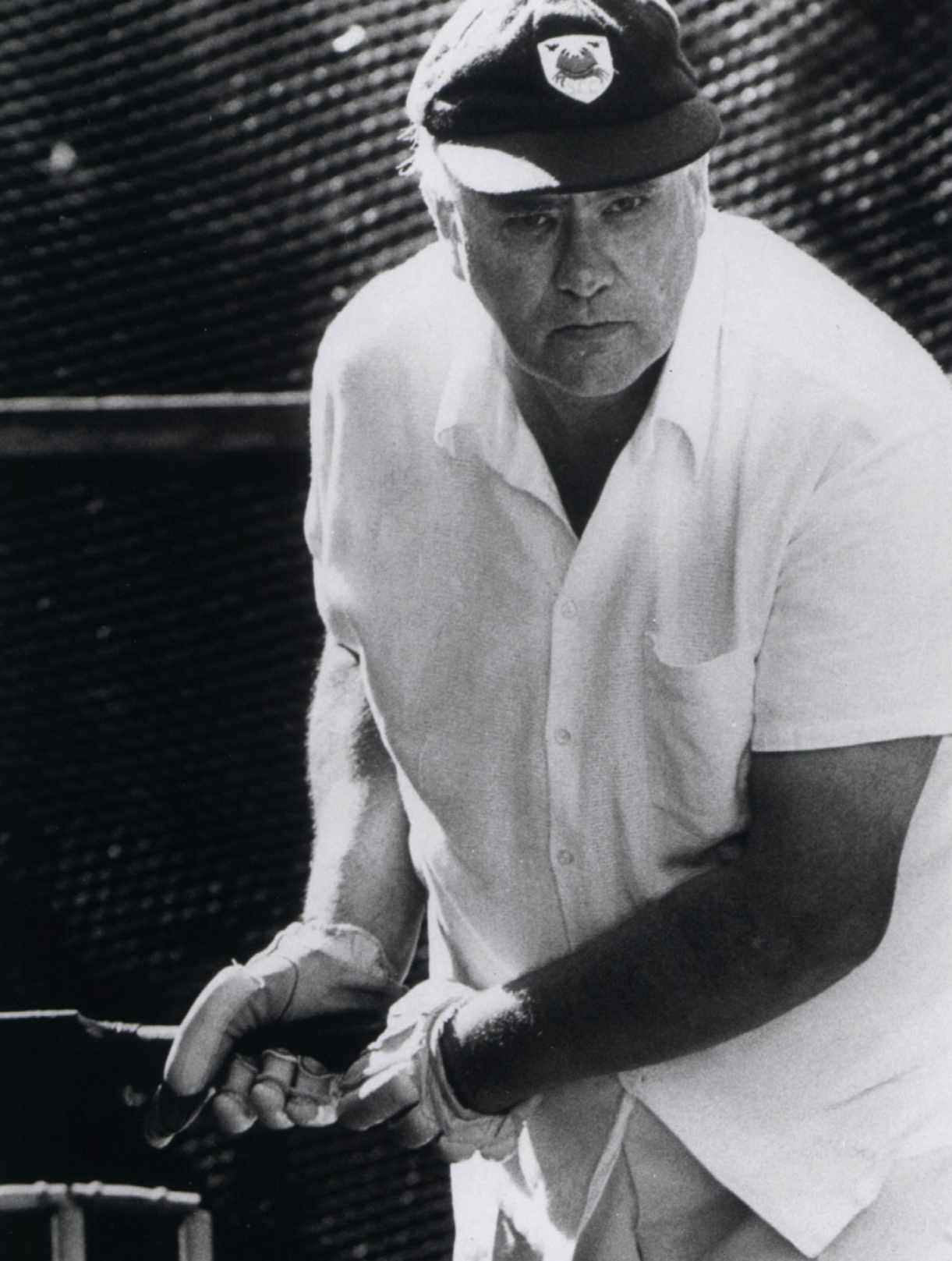

Patrick’s love of humour was apparent throughout much of his work and he was certainly never afraid to laugh at himself. He performed TV comedy alongside the likes of Michael Bentine, Morecambe and Wise, and Jon Culshaw, and once joined the Flat Earth Society as a joke. Although best-known for his TV work, Patrick also gave many public lectures, including three nationwide tours of provincial theatres in the 1990s.

Patrick’s career as a writer extended to the news media, as he contributed countless articles to newspapers and magazines. At various times, he was an editor and consultant for a number of astronomy magazines in the UK, giving his full support to BBC Sky at Night Magazine when it launched in 2005, becoming the magazine’s Editor Emeritus and writing two columns in each issue until he died in December 2012. He regularly received recognition for his work, accumulating an impressive array of honours including an honorary fellowship of the Royal Society, a BAFTA, an OBE, a CBE, a knighthood and numerous honorary doctorates.

On Patrick’s death in 2012, Britain lost a national treasure; a larger-than-life character, yet also a man of deep compassion who was quick to make friends. For many decades he was the public voice of astronomy, raising awareness and helping countless amateur astronomers to pursue their hobby. Just as crucially, he inspired generations of professional astronomers and a multitude of writers and broadcasters to educate a fascinated public about its wonders.

A version of this article appeared in BBC Sky at Night Magazine’s special issue The Extraordinary Life of Sir Patrick Moore, published in 2012

Patrick’s telescopes

From a 3-inch refractor to a 15-inch reflector, Patrick owned a range of instruments throughout his life

3-inch brass refractor

His first telescope, bought at age 11, was this Broadhurst Clarkson 3-inch refractor on a pillar-and-claw mount. His first paper was based on the observations he made with it. It was restored in 2008 by Telescope House, the retail arm of the same makers who sold it to Patrick in the 1930s.

12.5-inch reflector

Purchased after the Second World War, Patrick’s first reflector ended up with a Henry Wildey mirror and sat atop a Ron Irving altazimuth mount. Housed in a run-off observatory, Patrick used it to map the Moon, including finding and naming the Mare Orientale in 1946.

8.5-inch reflector

When the Royal Greenwich Observatory moved to Herstmonceux, East Sussex, in the early 1950s, Patrick bought this surplus scope, an 8.5-inch With-Browning reflector. He housed it in an octagonal observatory. It was almost blown away by a tornado in 1998.

5-inch refractor

Acquired in the 1960s, this was made by the famous 19th-century telescope-maker Thomas Cooke. Its mount was a Charles Frank equatorial design and it was housed in a run-off-roof observatory. It was restored by telescope craftsman Steve Collingwood.

15-inch reflector

Rounding off Patrick’s collection was this 15-inch reflector, with a mirror re-figured by George Hole. It was mounted on a Fullerscopes fork mount, housed in a rotating ‘oil drum’-style observatory and was used mainly to study the Moon and planets.